Abstract

We present a systemic theoretical study of the electronic properties of the quantum dots inserted in quantum dot infrared photodetectors (QDIPs). The strain distribution of three different shaped quantum dots (QDs) with a same ratio of the base to the vertical aspect is calculated by using the short-range valence-force-field (VFF) approach. The calculated results show that the hydrostatic strain ɛHvaries little with change of the shape, while the biaxial strain ɛBchanges a lot for different shapes of QDs. The recursion method is used to calculate the energy levels of the bound states in QDs. Compared with the strain, the shape plays a key role in the difference of electronic bound energy levels. The numerical results show that the deference of bound energy levels of lenslike InAs QD matches well with the experimental results. Moreover, the pyramid-shaped QD has the greatest difference from the measured experimental data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to three-dimensional confinement for electrons in the quantum-dot structure, quantum-dot infrared photodetectors (QDIPs) have attracted much attention for theoretical and experimental studies in recent years [1–3]. One important characteristic for QDIPs is the sensitivity to normal-incidence infrared radiation which is advantage to focal plane arrays. The longer lifetime of excited electrons inspirited by the greatly suppressed electron–phonon interaction makes the QDIPs have another advantages of displaying low dark current, large detectivity, and better response [4]. The introduction of strain may provide a facile way to fabricate various wavelength from mid-wavelength to long-wavelength multicolor infrared (IR) detectors via InAs or InGaAs quantum dot (QD) capped by GaAs, InGaAs, InP, or GaInP. Meanwhile, the geometry shape of QDs always results in quite different responding wavelength for QDIPs [5]. Nowadays, more complicated nanostructures, such as QD molecules are investigated for the potential use of photoelectric devices [6]. It is well known that the much sensitivity of QD’s bound energy levels to the shape, size, and strain provides the detector greater potential to obtain the ideal responding wavelength for the application of medical or molecular application. So the study of the shape, size, and strain of QD system has been an interesting subject for the development and precious controlling of the QDIPs structure.

Much theoretical and experimental work has been done to explore the effect of the shape, size, or strain of QDs on the bound energy levels or the possible optical transition. The bound energy levels in fat lenslike QD basing on the quantum-well approximate theoretical results have a bigger difference by comparing to the experimental results. In wojs’ work, the energy levels of lenslike In0.5Ga0.5As/GaAs QD were studied as a function of the dot’s size, and found that the parabolic confining potential and its corresponding energy spectrum were shown to be and excellent approximation [7]. Here, we calculate the strain energy of self-assembled QDs with the short-range valence-force-field (VFF) approach to describe inter-atomic forces by using bond stretching and bending. The role of strain (for three different shapes) in determining the bound levels is analyzed in detail. Considering three different shape QDs with the same ratio of the base to the vertical aspect 3:1, the bound energy levels are calculated by the recursion method [3]. The theoretical results show that the difference of bound energy levels of lenslike InAs QD matches with the experimental results. While the bound energy levels of pyramid-shaped QD have the biggest difference from the measured experimental data. Though the bound-to-continuum transition of the truncated pyramid QD is mostly acceptable because the behavior is much similar to the structure of the well-studied quantum-well infrared photodetectors (QWIPs), the bound ground states of electrons and holes are very far from the experimental results.

The paper is organized as following, in the section “Sample Preparations and Experimental Results,” the investigated experimental device and experimental results such as AFM/TEM images, the photoluminescence (PL), and photocurrent (PC) spectrums are described. In the section “Theoretical Results and Discussions,” the exact strain distributions of pyramid, truncated pyramid, and lenslike-shaped InAs/GaAs QD are calculated by the short-range VFF approach, and the energy levels of the bound states are calculated by the recursion method. The final section discusses the summary.

Sample Preparations and Experimental Results

Figure 1shows a schematic of the QDIP structure. The sample was grown on semi-insulating GaAs (001) substrates by using the solid-source molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). Five layers of nominally 3.0 momolayer (ML) InAs (quantum dots) were inserted between highly Si-doped bottom and top GaAs 1000 nm contact layers with doping density 1 × 1018 cm−3. Each layer of InAs is capped by 21 ML spacer GaAs material to form the InAs QDs, and the five layers of GaAs/InAs are called S-QD. In addition there is a 50 nm GaAs layer inserted between the S-QD regions and bottom (top) Si-doped GaAs contact layers, respectively.

The typical constant-mode ambient atomic force microscopy (AFM) data and the cross-sectional TEM for the counterpart samples are present in Fig. 2a and b, respectively. The average height of quantum dots is about 74 ± 16 Å, and the quantum dot density has a range from 613/um2to 733/um2. The average quantum dot width with the range from 228 to 278 Å represents the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of AFM scan profile. Figure 2b shows that the cross-sectional transmission electron microscope images on the S-QD counterpart. It is noted that the quantum dot density in the lower layer is higher than that in the upper layer.

The near-infrared photoluminescence (PL) as a function of energy at 77 K is shown in Fig. 3. A main peak corresponding to the quantum dot ground state transitions is centered at 1.058 eV and a small broad shoulder due to smaller quantum dots or InAs wetting layer appears at 1.216 eV. Figure 4shows the intra-band photocurrent as a function of energy at 77 K in the absence of bias. It is well known that the intra-band photocurrent can present more direct information on the quantum dot electronic states. An obvious intra-band photocurrent peak appears at 170.675 meV.

Theoretical Results and Discussions

Strain and Confinement Profile

Here, we adopt the short-range VFF approach to describe interatomic forces in terms of band stretching and bending [8, 9]. The model has been widely applied in bulk and alloys [10–14], as well as low-dimensional systems [15, 16]. It was further developed to an enharmonic VFF model by Bernard and Zunger for Si–Ge compounds, alloys and superlattices [17]. In the VFF model, the deformation of a lattice structure is completely specified when the location of every atom in a strained state is given [18], and the elastic energy of a bond is minimal in its three-dimensional bulk lattice structure. For small deformations, the bond energy can be written as a Taylor expansion in the variations of the bond length and the angles between the bond and its nearest neighbor bonds. Under the rubric of short-range contributions and by following the general notations in Ref. [9–14], the elastic energy of an interatomic bond (by setting the elastic energy at equilibrium as the zero reference) can be written in the harmonic form,

with j = 1,2...6 denoting the six nearest neighbor bonds in zinc blende structure. δr

i

is the variation of the length of bond i, and δΩ

ij

is the variation of the angle between the i’th and the j th bonds. The total elastic energy is the sum of all bond energies  The numerical values of K’s for VFF bonds of zinc blende bulk materials are easily obtained from elastic coefficients C

11

C

12, and C

44 listed in Ref. [17]. Table 1 lists the C and K values for InAs and GaAs. Note that K’s values depend slightly on the temperature of the material due to the temperature dependence of the lattice constant. The dependence, however, is small. The values listed in Table 1 are obtained for the materials at 100 K.

The numerical values of K’s for VFF bonds of zinc blende bulk materials are easily obtained from elastic coefficients C

11

C

12, and C

44 listed in Ref. [17]. Table 1 lists the C and K values for InAs and GaAs. Note that K’s values depend slightly on the temperature of the material due to the temperature dependence of the lattice constant. The dependence, however, is small. The values listed in Table 1 are obtained for the materials at 100 K.

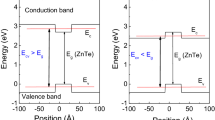

The local band edges employing the following formulas for the conduction (CB), the heavy hole (HH), and the light hole (LH) bands can be approximated as:

where the hydrostatic strain ɛH and the biaxial strain ɛB are defined as

V HH and V LH are the heavy-hole and light-hole bands, a c a v and b are the deformation potentials, and E CB/VB are the unstrained band edge energies. Notice that the sheer-strain-induced HH–LH coupling and split-off contributions are ignored. In our calculation we adopt the parameters from Ref. [17].

The investigated three different shaped InAs QDs follows pyramid-shaped (with the four facets being (111),

and

and  InAs QD with the height and base being 81 and 162 Å, respectively, truncated pyramid-shaped (with the four facets being same with these of pyramid-shaped QD) InAs QD with the height and base being 80 and 168 Å, respectively, and lense-shaped InAs QD with the height and diameter being 80 and 240 Å, respectively. The distribution and value of strain is mainly determined by two factors. The first factor is the shape and volume of QD. Based on InAs and GaAs technology and the Stranski-Krastanov self-assembly technique, the QD can have different shape and symmetry, which therefore has effect on the strain distribution in QD and the corresponding band offset. The second one is the degree of anisotropy of elastic property, which is described by elastic constants. In our calculation, the QDIP system is made up of InAs/GaAs. So, the second term has the same impact on the strain distribution. In the following, we will have a look at the relationship of the strain distribution and the shape of QDs. The typical results are shown in Fig. 5. The hydrostatic strain ɛHmakes the height of CB lower, but the height changes are almost same for different shape of QDs. While the biaxial strain ɛBis rather complex for the three different shapes. For the lens-shaped QD, the InAs lattice is compressed by GaAs in the growth plane and stretched in the plane, which is vertical to the growth plane. The pyramid-shaped QD is more complex. The lattice of the top of QD is stretched in the growth plane, and in the central ɛB = 0, which means that there is no splitting for the valence band in the position. The compressing and stretching condition of bottom in the pyramid QD is the same as the lens-shaped QD. The difference of QD shape makes the strain distribution rather different, and the calculated strain distribution of truncated-pyramid QD resembles to that of the pyramid-shaped QD. The existence of GaAs coating makes the strain distribution at the top of the three different shapes of QD to present different characters as: ɛH < 0 and ɛB < 0 for lenslike and truncated-pyramid QD; and ɛH < 0 and ɛB > 0 for pyramid-shaped QD. Figure 6shows the calculated confinement potential distribution induced with the strain for three different shaped QD. The potential has different characters. The difference of electron energy levels mainly comes from the difference of shape because there is little change in the value of ɛHfor different shaped QDs. The role of hydrostatic strain ɛHmakes the height of CB less. The splitting of hole potential is determined by biaxial strain ɛB, which changes a lot when the shape varies.

InAs QD with the height and base being 81 and 162 Å, respectively, truncated pyramid-shaped (with the four facets being same with these of pyramid-shaped QD) InAs QD with the height and base being 80 and 168 Å, respectively, and lense-shaped InAs QD with the height and diameter being 80 and 240 Å, respectively. The distribution and value of strain is mainly determined by two factors. The first factor is the shape and volume of QD. Based on InAs and GaAs technology and the Stranski-Krastanov self-assembly technique, the QD can have different shape and symmetry, which therefore has effect on the strain distribution in QD and the corresponding band offset. The second one is the degree of anisotropy of elastic property, which is described by elastic constants. In our calculation, the QDIP system is made up of InAs/GaAs. So, the second term has the same impact on the strain distribution. In the following, we will have a look at the relationship of the strain distribution and the shape of QDs. The typical results are shown in Fig. 5. The hydrostatic strain ɛHmakes the height of CB lower, but the height changes are almost same for different shape of QDs. While the biaxial strain ɛBis rather complex for the three different shapes. For the lens-shaped QD, the InAs lattice is compressed by GaAs in the growth plane and stretched in the plane, which is vertical to the growth plane. The pyramid-shaped QD is more complex. The lattice of the top of QD is stretched in the growth plane, and in the central ɛB = 0, which means that there is no splitting for the valence band in the position. The compressing and stretching condition of bottom in the pyramid QD is the same as the lens-shaped QD. The difference of QD shape makes the strain distribution rather different, and the calculated strain distribution of truncated-pyramid QD resembles to that of the pyramid-shaped QD. The existence of GaAs coating makes the strain distribution at the top of the three different shapes of QD to present different characters as: ɛH < 0 and ɛB < 0 for lenslike and truncated-pyramid QD; and ɛH < 0 and ɛB > 0 for pyramid-shaped QD. Figure 6shows the calculated confinement potential distribution induced with the strain for three different shaped QD. The potential has different characters. The difference of electron energy levels mainly comes from the difference of shape because there is little change in the value of ɛHfor different shaped QDs. The role of hydrostatic strain ɛHmakes the height of CB less. The splitting of hole potential is determined by biaxial strain ɛB, which changes a lot when the shape varies.

The Calculation and Analysis of the Energy Level

The recursion method is used to calculate the energy levels of three different shaped QDs [20]. For the experimental data, the broadening (FWHM) of the PC spectrum and the first peak of the PL spectrum are 34.01 and 29.34 meV, respectively. The broadening is 131.42 meV for the second peak. The much greater difference in the FWHM implies the possibility that the second peak comes from wetting layer, but not from the bound levels of QDs. So for the simplicity of comparing with the experimental results, we only calculate all the energy levels of electron and the bound ground energy level of hole with the corresponding results shown in Fig. 6 (dotted line).

Next, we present the change in energy level for three different shape QDs. From Fig. 6, some results are found. The energy difference between the ground states of hole and electron is 0.990 eV for pyramid QD, 1.215 eV for truncated pyramid QD, and 1.053 eV for lens-shaped QD, respectively. The possible bound-to-bound transition of electronic inter-subbands is 254.1 meV for pyramid QD and 156.4 meV for lens-shaped QD. There is only one bound state in conduction band, so the possible transition of different energy levels is bound-to-continuum state with the energy being 199.3 meV. From the experimental data, the PL spectrum presents the ground state transition from electron to hole with the value being 1.058 eV. Compared with the experimental data, the corresponding calculated value has the difference (d PL) of 6.43% for pyramid QD, 14.8% for truncated-pyramid QD, and 0.47% for lens-shaped QD. Also the differences (d PC) from the measured PC peak (170.675 meV) are 48.88%, 16.77%, and 8.36% for pyramid, truncated-pyramid, and lens-shaped QD, respectively. The compared results show that the energy difference of the lens-shaped QD is the most favored for the possible QD structure. Though the transition of the bound-to-continuum transition for truncated pyramid QD is mostly acceptable because the behavior is much like the well-studied QWIP structure, the energy difference of the bound ground states between electron and hole is rather far from the experimental results. The pyramid is not possible to be the shape of our investigated QD for the biggest difference of 48.88%. If we define a parameter σ to estimate whether the shape or size is the most favored to QD of investigated QDIP structure, the most suitable expression should be

with d PL and d PC being the difference of calculated and measured PL and PC spectrum, respectively. In our calculation, σ is 34.86%, 15.82%, and 5.92% for pyramid, truncated-pyramid, and lens-shaped QD, respectively. For the lens-shaped QD, σ has the least value, which means the QDIP structure is constructed by the lens-shaped QD. The lens-shaped InAs/GaAs QD is observed by many researchers, and in this way our calculation can get a good agreement with the measured data. Also the PL, PC spectrum, and σ provide us a way to find out the most suitable shape and size of QD which makes σ the minimum. The different shape of QDs can have different response wavelength as described in our calculation. The results mean that one can obtain the ideal response wavelength of QDIP structure by controlling the growth condition to change the shape of QDs.

Summary

In summary, we have studied the strain distribution of self-assembled QD by the short-range VFF approach to describe inter-atomic forces in terms of bond stretching and bending. The strain-driven self-assembled process of QD based on lattice mismatch has been clearly demonstrated. The recursion method is used to calculate the bound energy levels of QD for three different shapes but at the same ratio 3:1 for the base to the vertical aspect. For the three different shaped QD, the hydrostatic strain ɛHhas a little change. The results indicate that the difference of bound energy is mainly controlled by the shape. The biaxial strain ɛBchanges a lot with the shape. Moreover, the strain and the shape both play key role in determining the ground state of hole. The results show that the difference of bound-to-bound energy levels of lenslike InAs QD matches well with the experimental data, while the pyramid-shaped QD has the biggest difference from the measured data. Though the bound-to-continuum transition for truncated pyramid QD is mostly acceptable because the behavior is much like the well-studied QWIP structure, the bound ground states between electron and hole value is rather far from the experimental results. Also the biggest difference of 48.88% makes the pyramid an impossible shape for our investigated QD. Our theoretical investigation provides a feasible method for finding the most seemly geometry and size of QDIP structure by adjusting the shape/size of QD and the comparing theoretical and experimental results. It is useful in designing the ideal QDIPs device.

References

Naser M A, Deen M J, Thompson D A: Spectral function and responsivity of resonant tunneling and superlattice quantum dot infrared photodetectors using Green’s function. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102: 083108. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXht1Gkt7bI] 10.1063/1.2799075

Ryzhii V, Mitin V, Stroscio M: On the detectivity of quantum-dot infrared photodetectors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 78: 3523. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3MXjvFWitbw%3D] 10.1063/1.1376435

Chen Z H, Baklenov O, Kim E T, Mukhametzhanov I, Tie J, Madhukar A, Ye Z M, Campbell J C: Normal incidence InAs/AlxGa1-xAs quantum dot infrared photodetectors with undoped active region. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 89: 4558. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3MXitlGiurk%3D] 10.1063/1.1356430

Wang S Y, Lin S D, Wu H W, Lee C P: Low dark current quantum-dot infrared photodetectors with an AlGaAs current blocking layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 78: 1023. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3MXht1Oiurk%3D] 10.1063/1.1347006

Jiang J, Tsao S, O’Sullivan T, Zhang W, Lim H, Sills T, Mi K, Razeghi M, Brown G J, Tidrow M Z: High detectivity InGaAs/InGaP quantum-dot infrared photodetectors grown by low pressure metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84: 2166. xCOI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXitlKku7Y%3D] 10.1063/1.1688982

Li S S, Xia J B: Electronic structure of N quantum dot molecule. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91: 092119. xCOI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXhtVCgtLjM] 10.1063/1.2778541

Wojs A, Hawrylak P, Fafard S, Jacak L: Electronic structure and magneto-optics of self-assembled quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54: 5604. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK28XlsVOmtLY%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.5604

Musgrave M J P, Pople J A: A general valence force field for diamond. Proc. R. Soc. Lond A 1962, 268: 474. 10.1098/rspa.1962.0153

Keating P N: Effect of invariance requirements on the elastic strain energy of crystals with application to the diamond structure. Phys. Rev. 1966, 145: 637. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaF28XpvVGlug%3D%3D] 10.1103/PhysRev.145.637

Nusimovici M A, Birman J L: Lattice dynamics of wurtzite: CdS. Phys. Rev. 1967, 156: 925. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaF2sXksVyjurY%3D] 10.1103/PhysRev.156.925

Martin R M: Elastic properties of ZnS structure semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1970, 1: 4005. 10.1103/PhysRevB.1.4005

Ramani R, Mani K K, Singh R P: Valence force fields and the lattice dynamics of beryllium oxide. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 14: 2659. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaE28XlvVCit7o%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevB.14.2659

Saito T, Arakawa Y: Atomic structure and phase stability of InxGa1-xN random alloys calculated using a valence-force-field method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60: 1701. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK1MXktlahu7Y%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevB.60.1701

Takayama T, Yuri M, Itoh K, Baba T, Harris J S: Theoretical analysis of unstable two-phase region and microscopic structure in wurtzite and zinc-blende InGaN using modified valence force field model. J. Appl. Phys. 2000, 88: 1104. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXksV2itLg%3D] 10.1063/1.373783

Jiang H, Singh J: Strain distribution and electronic spectra of InAs/GaAs self-assembled dots: an eight-band study. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56: 4696. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK2sXlvVSjtbY%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevB.56.4696

Stier O, Grundmann M, Bimberg D: Electronic and optical properties of strained quantum dots modeled by 8-band k·p theory. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59: 5688. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK1MXhtF2msLc%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.5688

Bernard J E, Zunger A: Strain energy and stability of Si-Ge compounds, alloys, and superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44: 1663. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK3MXlsVKqtbs%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevB.44.1663

Birman J L: Theory of the piezoelectric effect in the zincblende structure. Phys. Rev. 1958, 111: 1510. xCOI number [1:CAS:528:DyaG1MXhsVKnug%3D%3D] 10.1103/PhysRev.111.1510

Vurgaftman I, Meyer J R, Ram-Mohan L R: Band parameters for III-V compound semiconductors and their alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 89: 5815. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3MXkt1Wrt74%3D] 10.1063/1.1368156

Fu Y, Willander M, Lu W, Liu X Q, Shen S C, Jagadish C, Gal M, Zou J, Cockayne D J H: Strain effect in a GaAs-In0.25Ga0.75As-Al0.5Ga0.5 As asymmetric quantum wire. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61: 8306. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXhvVSgs74%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevB.61.8306

Acknowledgments

The project is partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No:10474020), CNKBRSF 2006CB13921507, and Knowledge Innovation Program of CAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, XF., Chen, XS., Lu, W. et al. Effects of Shape and Strain Distribution of Quantum Dots on Optical Transition in the Quantum Dot Infrared Photodetectors. Nanoscale Res Lett 3, 534 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-008-9175-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-008-9175-8