Abstract

SiGe islands have been proposed for applications in the fields of microelectronics, optoelectronics and thermoelectrics. Although most of the works in literature are based on MBE, one of the possible advantages of low-energy plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (LEPECVD) is a wider range of deposition rates, which in turn results in the possibility of growing islands with a high Ge concentration. We will show that LEPECVD can be effectively used for the controlled growth of ordered arrays of SiGe islands. In order to control the nucleation of the islands, patterned Si (001) substrates were obtained by e-beam lithography (EBL) and dry etching. We realized periodic circular pits with diameters ranging from 80 to 300 nm and depths from 65 to 75 nm. Subsequently, thin films (0.8–3.2 nm) of pure Ge were deposited by LEPECVD, resulting in regular and uniform arrays of Ge-rich islands. LEPECVD allowed the use of a wide range of growth rates (0.01–0.1 nm s−1) and substrates temperatures (600–750°C), so that the Ge content of the islands could be varied. Island morphology was characterized by AFM, while μ-Raman was used to analyze the Ge content inside the islands and the composition differences between islands on patterned and unpatterned areas of the substrate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanostructures for microelectronic applications need to be well controlled in terms of the shape, ordering and composition. Since Ge islands tend to nucleate randomly on flat Si substrates, substrate patterning can be used to achieve controlled positioning by creating material traps [1, 2]. Besides positioning the SiGe structures on the substrate, an appropriate pattern can also control their size. Using electron beam lithography (EBL), it is possible to vary width, depth and spacing of seed holes in order to trap the deposited material in a controlled way. This method allows strain relaxation in islands to also be controlled [3]. Similarly, it is also necessary to control the composition, since this parameter influences a number of electronic and optical properties [4–6].

In this paper, we use EBL and reactive ion etching (RIE) to realize periodical seed holes in Si substrates. The deposition of a few layer of Ge directly on Si-patterned substrates by LEPECVD results in the nucleation of SiGe islands at the preferential sites. We investigate the impact of the LEPECVD technique on composition and strain relaxation of SiGe islands using AFM and μ-Raman spectroscopy.

Experimental Procedure

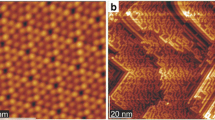

Pit-patterned Si substrates were prepared by EBL upon a surface cleaned by an ultrasonic treatment with organic solvents. Then, two layers of poly(methyl methacrylate) were deposited by spinning (3,000 rpm) and baking for 1 h at 160°C. During EBL, different doses were used (250, 300, 350 and 400 μC cm−2) to create pits with final diameter between 80 and 300 nm. For every exposure, the patterned area was 25 × 25 μm2 with pits at a regular spacing of 1 μm, and 70–75 nm of Si was etched by RIE. After RIE, all samples were analyzed by scanning electron microscope and AFM to check the depth and quality of etching (Fig. 1). To obtain a clearer visualization of the surface in all the images shown in this work, we have used a grayscale corresponding to the surface gradient [7, 8]. The image edges are <110> directions.

Pure Ge was deposited by LEPECVD [9, 10] directly on the cleaned patterned Si (001) substrates at different temperatures between 600 and 750°C. The thickness of deposited Ge ranged from 0.8 to 3.2 nm, while the growth rate was either 0.015 or 0.1 nms−1.

The distribution and size of the islands were characterized by AFM, while the Ge content was measured using μ-Raman spectroscopy. All AFM analyses were carried out in tapping mode using an Innova–Veeco instrument with ultra sharp tip (typical curvature radius 2 nm). The μ-Raman spectra were acquired in back-scattering configuration with a 532-nm excitation wavelength in order to obtain a high signal-to-noise ratio with Ge-rich structures [11]. Due to self-absorption, the investigated depth corresponds to about one half of the penetration depth d p, ranging from about 10 to 40 nm in Ge-rich Si1−x Ge x alloys. The microscope features a 100 ×/0.90NA objective with a spatial resolution of 360 nm. The spectral positions of the SiGe alloy vibrational bands were used to measure both the strain and Ge content [12, 13].

Results and Discussion

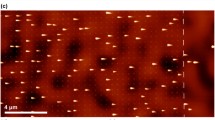

At low temperature (600°C) as shown in Fig. 2a, the mobility of Ge atoms was too low, and we obtained small islands between patterned areas. Increasing the temperature (750°C), the Ge mobility increases [14, 15], and we obtained 3D islands positioned correctly (Fig. 2c) with only very few islands between the pits. At this temperature, we varied the amount of deposited Ge to investigate the trapping effect of the holes [16]. In the range of amount of deposited Ge (0.9–3.2 nm), we did not observe islands in the region between the holes. Following models reported in literature [14, 17], this means that the migration length of Ge adatoms ( with D the diffusion coefficient) is greater than the distance between the holes. For a fixed patterning dimension, the island volume increases proportionally to the thickness of the deposited Ge. From high-resolution AFM scans, we can identify {105}, {113} and {15 3 23} facets at the sides of the islands and {1 1 10} facets near their tops, while the tops themselves are parallel to (001).

with D the diffusion coefficient) is greater than the distance between the holes. For a fixed patterning dimension, the island volume increases proportionally to the thickness of the deposited Ge. From high-resolution AFM scans, we can identify {105}, {113} and {15 3 23} facets at the sides of the islands and {1 1 10} facets near their tops, while the tops themselves are parallel to (001).

AFM gradient images of a patterned area following the deposition of 2.8 nm of Ge at 600°C (a), 700°C (b) and 750°C (c). The growth rate was 0.1 nm s−1. At low temperature (a), we have formation of small SiGe 3D structures around pits. They are also observed at intermediate temperature (b), although in smaller quantity. At high temperature (c), only very few islands are formed which are not on the top of pits, and some pits appear to be uncapped with islands

We evaluated the effect of growth rate on the positioning and composition of the islands. The growth rates were 0.1 or 0.015 n ms−1. At these growth rates, keeping the other growth parameters fixed, we did not observe island formation between pits. This result has been expected, because by low growth rate we reduce the Ge adatom concentration, and consequently we decrease the possibility of nucleating new islands between pits. The volume of the islands changed: the structures grown at high growth rates have a lower volume and the aspect ratio (AR, which is defined as the height h divided by the square root of the base area A); those obtained at low rates have larger volume, and the AR is comparable to islands grown by MBE at the same temperature and growth rates (Fig. 3a, 3b) [18]. The effect of Ge thickness and growth rates described above has been characterized also by μ-Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 4). In Table 1, we report results on the Ge content for different Ge thickness deposited and growth rates. μ-Raman analyses show that if we increase the Ge thickness, the Ge content in the island increases. The residual strain measured by μ-Raman spectroscopy is always very small and of tensile nature, which probably indicates plastic relaxation at the growth temperature followed by thermal stress on cooling to room temperature. The Ge content of islands within the pattern does not change significantly when the growth rate is reduced from 0.1 to 0.015 nm s−1 despite the increase in volume.

Examples of μ-Raman spectroscopy results obtained from single island inside the pattern (black data) and island outside the pattern (red data). The data refer to islands grown with a total amount of 2.8 nm of Ge with a 0.1 nm s−1 rate with a substrate temperature of 750°C. a Semilogarithmic plot of the Raman spectra with the indication of the three bands related to the islands (marked with Si–Si, Si-Ge and Ge–Ge) and the single band related to the Si bulk substrate. b Composition-strain plane showing the calibration curves extracted from Ref. [12] corresponding to the peaks shown in panel (a). The intersection of the curves is highlighted with the dot and marks the value of composition and strain for the islands. The method is described in detail in Ref. [13]

Conclusions

We have demonstrated regular SiGe islands on prepatterned substrate formed after the deposition of Ge by LEPECVD. In particular, we have analyzed by AFM and μ-Raman, the effects of temperature, thickness and growth rate on the shape, volume and composition of the SiGe islands. Optimal growth conditions for ordered Ge-rich island formation were found for the chosen geometry of the pattern.

References

Zhong Z, Bauer G: Appl. Phys. Lett.. 2004, 84: 1922. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXitFSnsLY%3D]; Bibcode number [2004ApPhL..84.1922Z] COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXitFSnsLY%3D]; Bibcode number [2004ApPhL..84.1922Z] 10.1063/1.1664014

Zhong Z, Schmidt OG, Bauer G: Appl. Phys. Lett.. 2005, 87: 133111. Bibcode number [2005ApPhL..87m3111Z] Bibcode number [2005ApPhL..87m3111Z] 10.1063/1.2061870

Katsaros G, Tersoff J, Stoffel M, Rastelli A, Acosta-Diaz P, Kar GS, Costantini G, Schmidt OG, Kern K: Phys. Rev. B. 2008, 101: 096103. COI number [1:STN:280:DC%2BD1cnlsleqtg%3D%3D] COI number [1:STN:280:DC%2BD1cnlsleqtg%3D%3D] 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.096103

Chen G, Lichtenberger H, Bauer G, Jantsch W, Schffler F: Phys. Rev. B. 2006, 74: 035302. Bibcode number [2006PhRvB..74c5302C] Bibcode number [2006PhRvB..74c5302C] 10.1103/PhysRevB.74.035302

Pezzoli F, Stoffel M, Merdzhanova T, Rastelli A, Schmidt OG: Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2009, 4: 1073. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXhtVCmtb7E]; Bibcode number [2009NRL.....4.1073P] COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXhtVCmtb7E]; Bibcode number [2009NRL.....4.1073P] 10.1007/s11671-009-9360-4

Rastelli A, Stoffel M, Malachias A, Merdzhanova T, Katsaros G, Kern K, Metzger TH, Schmidt OG: Nano Lett.. 2008, 8: 1404. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXktVGitLc%3D]; Bibcode number [2008NanoL...8.1404R] COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXktVGitLc%3D]; Bibcode number [2008NanoL...8.1404R] 10.1021/nl080290y

Rastelli A, von Knel H: Surf. Sci.. 2002, 515: L493. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD38Xmtlert7Y%3D] COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD38Xmtlert7Y%3D] 10.1016/S0039-6028(02)01998-2

Kamins TI, Medeiros-Ribeiro G, Ohlberg DAA, Williams RS: J. Appl. Phys.. 1999, 85: 1159. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK1MXit1answ%3D%3D]; Bibcode number [1999JAP....85.1159K] COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK1MXit1answ%3D%3D]; Bibcode number [1999JAP....85.1159K] 10.1063/1.369255

Rosenblad C, von Knel H, Kummer M, Dommann A, Mller E: Appl. Phys. Lett.. 2000, 76: 427. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXlvVartQ%3D%3D]; Bibcode number [2000ApPhL..76..427R] COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXlvVartQ%3D%3D]; Bibcode number [2000ApPhL..76..427R] 10.1063/1.125776

Bollani M, Chrastina D, Fedorov A, Isella G, Sordan R: Proc. SPIE Nanotechnol. IV. 2009, 7364: 7364 0I.

Picco A, Bonera E, Grilli E, Guzzi M, Mariotto G, Chrastina D: Phys. Rev. B. 2010., 82: in press in press

Pezzoli F, Bonera E, Grilli E, Guzzi M, Sanguinetti S, Chrastina D, Isella G, von Knel H, Wintersberger E, Stangl J, Bauer G: J. Appl. Phys.. 2008, 103: 093521. Bibcode number [2008JAP...103i3521P] Bibcode number [2008JAP...103i3521P] 10.1063/1.2913052

Pezzoli F, Bonera E, Grilli E, Guzzi M, Sanguinetti S, Chrastina D, Isella G, von Knel H, Wintersberger E, Stangl J, Bauer G: Mat. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2008, 11: 279. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXht1Crsb3F] COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1MXht1Crsb3F] 10.1016/j.mssp.2008.09.012

Drucker J, Chaparro S: Appl. Phys. Lett.. 1997, 71: 614. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK2sXltFymuro%3D]; Bibcode number [1997ApPhL..71..614D] COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK2sXltFymuro%3D]; Bibcode number [1997ApPhL..71..614D] 10.1063/1.119809

Zhong Z, Chen P, Jiang Z, Bauer G: Appl. Phys. Lett.. 2008, 93: 043106. Bibcode number [2008ApPhL..93d3106Z] Bibcode number [2008ApPhL..93d3106Z] 10.1063/1.2965484

Dais C, Solak HH, Mller E, Grtzmacher D: Appl. Phys. Lett.. 2008, 92: 143102. Bibcode number [2008ApPhL..92n3102D] Bibcode number [2008ApPhL..92n3102D] 10.1063/1.2907196

Kamins TI, Williams RS: Appl. Phys. Lett.. 1997, 71: 1201. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK2sXlsl2qs7s%3D]; Bibcode number [1997ApPhL..71.1201K] COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK2sXlsl2qs7s%3D]; Bibcode number [1997ApPhL..71.1201K] 10.1063/1.119625

Marzegalli A, Zinovyev VA, Montalenti F, Rastelli A, Stoffel M, Merdzhanova T, Schmidt OG, Miglio L: Phys. Rev. Lett.. 2007, 99: 235505. COI number [1:STN:280:DC%2BD1c%2FnslSitQ%3D%3D]; Bibcode number [2007PhRvL..99w5505M] COI number [1:STN:280:DC%2BD1c%2FnslSitQ%3D%3D]; Bibcode number [2007PhRvL..99w5505M] 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.235505

Acknowledgments

The Cariplo Foundation is gratefully acknowledged for partially financing this research through the project MANDIS.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bollani, M., Bonera, E., Chrastina, D. et al. Ordered Arrays of SiGe Islands from Low-Energy PECVD. Nanoscale Res Lett 5, 1917 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-010-9773-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11671-010-9773-0

directions, respectively

directions, respectively