Abstract

To design a high-performance photocatalytic system with TiO2, it is necessary to reduce the bandgap and enhance the absorption efficiency. The reduction of the bandgap to the visible range was investigated with reference to the surface distortion of anatase TiO2 nanoparticles induced by varying Fe doping concentrations. Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticles (Fe@TiO2) were synthesized by a hydrothermal method and analyzed by various surface analysis techniques such as transmission electron microscopy, Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, scanning transmission X-ray microscopy, and high-resolution photoemission spectroscopy. We observed that Fe doping over 5 wt.% gave rise to a distorted structure, i.e., Fe2Ti3O9, indicating numerous Ti3+ and oxygen-vacancy sites. The Ti3+ sites act as electron trap sites to deliver the electron to O2 as well as introduce the dopant level inside the bandgap, resulting in a significant increase in the photocatalytic oxidation reaction of thiol (–SH) of 2-aminothiophenol to sulfonic acid (–SO3H) under ultraviolet and visible light illumination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Titanium oxide (TiO2) is one of the most promising materials for various applications such as solar cells, gas sensors, photocatalysis, and corrosion protection due to its chemical stability, nontoxicity, and low cost [1, 2]. Furthermore, its high oxidation properties have been applied to the degradation of organic pollutants [3–5]. However, the problems caused by the large bandgap (3.0–3.2 eV) result in poor efficiency and limited light absorption in the visible region, which makes a practical application difficult [6, 7]. To solve these chronic problems and enhance catalytic properties, narrowing the bandgap is necessary.

One strategy is co-deposition of a noble metal such as Pt, Ag, Au, or Pd onto the TiO2 surface. This strategy has little effect on narrowing the bandgap, although it does improve the separation of holes and electrons significantly [8–13]. However, it is not cost effective and makes almost no contribution to light absorption in the visible range. Another strategy is the introduction of foreign atoms as dopants inside the TiO2 substrate [14–16]. This can narrow the TiO2 bandgap and change the electronic band structure, which can increase the photocatalytic performance significantly. If the effect is similar or the same as that of noble metals, transition metals such as Fe, Co, and Ni are the most feasible and cost-effective dopant candidates. Such transition metals possess various oxidation states and thus contribute to bandgap control.

We introduced Fe ions into the TiO2 substrate using a hydrothermal method and systematically investigated the photocatalytic activities of Fe-doped TiO2 nanoparticle (Fe@TiO2) at various Fe doping concentrations. Structural and electronic changes were characterized by surface analysis techniques. The photocatalytic activities were characterized by the oxidation of 2-aminothiophenol (2-ATP) with different light sources in the ultraviolet (365 nm) and visible (540 nm) regions. We found that 5 wt.% of Fe dopants in TiO2 nanoparticles form a new distorted phase in which catalytic performance is significantly enhanced by bandgap narrowing.

Methods

Materials

Titanium isopropoxide (TTIP, 99.9 %), tetramethyl ammonium hydroxide solution (TMAOH, 25 wt.% in H2O), and Fe(NO3)3 9H2O (99.9 %) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

Preparation of Fe-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles

Preparation of Dispersed Fe@TiO2 Nanoparticle Solution

TMAOH (1.2 g) was introduced into a round-bottomed flask (100 ml) containing double-distilled water (22.25 g). The diluted TMAOH solution was stirred for 10 min. TTIP (3.52 g, 12.4 mmol) was separately diluted with isopropanol (3.5 g) and stirred for 10 min. The diluted TTIP was added dropwise into the TMAOH solution with vigorous stirring at room temperature. Initially, white TiO2 precipitants appeared. Then, a desired amount of Fe(NO3)3 9H2O (99.9 %) as a dopant was introduced into the synthetic gel solution. The round-bottomed flask containing the synthetic gel solution was placed in an oil bath. The temperature of the oil bath was maintained at 80 °C under continuous stirring. After approximately 10 min, the synthetic gel solution became a transparent solution. The synthetic gel was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave. The autoclave was placed in a convection oven preheated to 220 °C for 7 h. The produced Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and washed with copious amounts of DDW to remove unreacted chemicals. Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles are dispersed into aqueous solution with concentration 0.05 g/mL. The dispersed Fe@TiO2 nanoparticle solution turned deep yellow with increasing Fe dopant concentration (see Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Preparation of the Fe@TiO2 Dispersed Nanoparticle Layers

Silicon wafers (1 cm × 1 cm) were washed with absolute ethanol, sonicated, and dried with an N2 stream followed by oxygen plasma treatment for 3 min. The dispersed Fe@TiO2 nanoparticle solution was then spin coated onto the silicon wafers at 2000 rpm. Subsequently, the spin-coated layers were annealed at 600 °C for 12 h at a heating rate of 5 °C/min in ambient atmosphere.

Characterization

The X-ray diffractions (XRDs) of the Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles were obtained using a Rigaku D/Max-A diffraction meter by Ni-filtered Cu-Kα radiation (40 kV, 300 mA). The scans were obtained by 4°/min with 0.01° step size. Raman spectra were obtained using a spectrometer (Horiba, LabRAM ARAMIS) with a 514.5-nm Ar ion CW laser. The morphologies of the samples were characterized by performing field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, FEI Inspect F50) at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV and field-emission transmission electron microscopy (FE-TEM, FEI Tecnai G2 F30 S-Twin) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) was performed at the 10A beamline at the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL). A Fresnel zone plate with an outermost zone width of 25 nm was used to focus the X-rays onto the Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles on the TEM grids. The transmitted intensity was measured with a scintillation-photomultiplier tube. Image stacks were acquired at 695–745, 450–480, and 520–570 eV using X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to extract the Fe L-edge, Ti L-edge, and O K-edge spectra, respectively. High-resolution photoemission spectroscopy (HRPES) experiments were performed at the PAL 8A1 beamline equipped with an electron analyzer (Physical Electronics, PHI-3057). The Fe 2p, Ti 2p, O 1s, and S 2p core level spectra were obtained using photon energies of 770, 510, 590, and 230 eV, respectively, to enhance the surface sensitivity. The binding energies of the core level spectra were determined with respect to the binding energy (E B = 84.0 eV) of the clean Au 4f core level for the same photon energy.

Photocatalytic Oxidation Reactions

2-Aminothiophenol (C6H4SHNH2, Sigma-Aldrich, 99 % purity) was purified by turbo pumping prior to dosing onto the Fe@TiO2 samples. A direct dozer controlled by a variable leak valve was used to dose the molecules with the same amount of oxygen molecules onto the Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles. UV-visible light (λ = 365 nm, 550 nm) exposure was maintained at 8 W through the vacuum chamber quartz window. Chamber pressure was maintained at 1 × 10−6 Torr during dosing, and the number of exposed molecules was defined by the dosing time in seconds: 1 L (Langmuir) corresponds to 1 s dosing at 1 × 10−6 Torr.

Results and Discussion

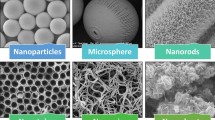

We first acquired TEM (Fig. 1) and SEM (Additional file 1: Figure S2) images varying the weight percent of the Fe dopants. SEM images were obtained from the Fe@TiO2 on Si substrate, and TEM images were obtained from the powder Fe@TiO2 by using a similar method. According to the morphology of both images, they show the same structural feature. When 1 wt.% was doped inside TiO2, very fine (70 nm) and homogeneous circular Fe@TiO2 particles are evident. These particles are much smaller than bare TiO2 particles (~200 nm). It is expected that the Fe ions act as nucleation sites and crystallize to particles as a fine structure. When the Fe dopant concentration was increased, particles with fine needle-like structure and big arrow structure are evident.

According to the fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern in the upper inset of the high-resolution TEM images, the big arrow structures in each image correspond to the highly ordered TiO2 structure in which particle grains are overlaid with other crystalline directions and indicate different FFT patterns. The expected pattern overlaps are indicated in the lower inset of Fig. 1. These big arrow structures were regarded as pure or low concentration Fe@TiO2 particles. When the Fe concentration increases to 3 and 5 wt.%, small needle structures are evident on both SEM and TEM images. Such structures are obtained as Fe2O3 complex by exclusion of Fe ions from the arrows structures. According to Additional file 1: Figure S3, EDX spectra show the portion of Fe atom in TiO2 substrates. At 5 wt.%, large arrow structures contain almost no Fe atom which also support the exclusion of Fe atom from the big arrow structures. Thus, these small needles (120 nm × 40 nm) are composed by bundling of smaller units, such as Fe2O3 and TiO2 structures. Those structures are dominant in 5 wt.% Fe@TiO2. XRD and Raman analyses (Fig. 2) elucidate the structural features with variation of concentration.

According to the XRD and Raman spectra shown in Fig. 2, anatase TiO2 structure is observed not only from 2θ = 25.27° and 48.05° with XRD (JCPDS#84-1286), which are associated with (101) and (200), but also from 144 (E g ), 196 (E g ), 392 (B 1g ), 520(A 1g ), and 638 (E g ) on the Raman spectra [17]. Those clearly identify the structure of anatase TiO2 with no polymorph features. According to the XAS spectra from STXM (Fig. 3), the ratio between two e g peaks of the Ti L-edge shows higher absorption of d z 2 (459.1 eV) compared to d x 2 − y 2 (460.0 eV), which is a typical XAS spectrum of the anatase TiO2 phase.

At 3 wt.% of Fe ions, the hematite-Fe2O3 structure appeared in the Raman spectra. When only a few layers of Fe2O3 were coated on the TiO2 surface, no XRD peak features were evident; however, coating with a small number of layers of Fe2O3 can cause lattice distortion. Additional file 1: Figure S4 shows the variation of the XRD peak position with the associated lattice constant of the (101) facet and the relative Raman intensity of E g (410)/E g (144) to elucidate the doping effects on structures. At 1 and 2 wt.% of Fe dopants, there are no Raman features with respect to Fe2O3, changing the lattice constant on XRD. This change occurs with the successful doping of Fe on the Ti substitutional sites. Such doping triggers the formation of oxygen vacancies to compensate the regional oxidation balance, which causes lattice contraction. At 3 wt.% of Fe dopants, the Raman spectrum of the hematite phase initially appears at 225, 245, 298, 409, and 611, which is associated with A 1g + 4E g [18]. Furthermore, the lattice constant of the (101) facet expands too close to the original phase. This means that the precipitation can be attributed to the phase separation between Fe2O3 and TiO2. At a higher doping concentration (5 wt.%), very small features of the anatase phase are shown by XRD. On the other hand, new structural features are indicated at 21.08° and 26.35°. These new structural features are contributions from the formation of a TiO2 composite with Fe2O3. According to previous investigations, the composite of (Cr, Fe)2Ti n − 2O2n − 1 indicates a monoclinic system, and their intergrowth can be attributed to the d-spacing changes from 18.9° to 22° as 2θ. In particular, in the case of n = 5, d-spacing near 25° and 27° is also evident. Thus, the spectrum is characterized as Fe2Ti3O9 (Fe2O3 3TiO2) [19–21].

The differences among the electronic structures of the samples were characterized by XAS measurements using STXM (Fig. 3). O K-edge XAS spectra has four peaks at 529.9, 532.3, 537.9, and 543.7 eV. Two peaks at 529.9 and 532.3 eV are attributed to the transition from O 1s orbital to the O 2p orbital hybridized with Ti 3d t 2g and e g states, respectively. Two additional peaks at 537.9 and 543.7 eV are attributed to the delocalized state of the Ti 4sp and O 2p bands. At 3 to 5 wt.% dopant concentrations, the peak at 532.3 eV is reduced. This may be because of the presence of surface-oxygen-vacancy sites that cause reduction in Ti 3d–O 2p hybridization in e g states and finally shows the reduction of intensity of 532.3 eV [22, 23]. This is also evident from the Ti L-edge spectra as well as the HRPES data.

Ti L 3,2-edge XAS spectra show the traditional anatase TiO2 structure, which arises from the transitions of Ti 2p electrons to unoccupied 3d electronic states in a distorted octahedral crystal field. Two t 2g , such as 457.4 and 462.7 eV, result from the transition of 2p 3/2 and 2p 1/2, respectively. Two e g bands, i.e., 459–460 and 464.8 eV, can be attributed to the transition from the 2p 1/2. When Fe ions are doped inside the TiO2, the intensity ratio of peaks t 2g (457.4 eV) to e g (459~460 eV) is gradually lowered compared with that of 1 wt.% Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles, which indicates a weak crystal field or an increment of the number of under-coordinated Ti atoms [24, 25]. Furthermore, the ratio of peaks d z 2 to d x 2 − y 2 indicates the distortion of the octahedral crystal field, which is noticeable in the discrepancy between the rutile and anatase structures. These ratios also decrease as the percentage of Fe dopants increases. Therefore, the anatase structure transforms to less crystalline anatase by the formation of Fe2O3 3TiO2. This transformation also gives rise to the surface defect structure, indicating that the small doublet at 456.0 and 456.6 eV is in the Ti3+ state [26].

L 3 and L 2-edges located at approximately 710 and 721 eV have been assigned as transitions from Fe 2p to an unoccupied 3d orbital. The distinct features at the L 3-edge indicate typical t 2g (706.0 eV) and e g (707.4 eV) splitting because of the presence of only the Fe3+ valence form. However, there is no noticeable oxygen state with respect to Fe2O3 [27–29].

The core level spectra (Fe 2p, Ti 2p, and O 1s) of the Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles were obtained with HRPES (Fig. 4) to determine the changes in electronic properties. According to the core level spectra of O 1s, the nanoparticles are composed of two different chemical environments assigned as TiO2 (530.9 eV) and Fe2O3 (533.0 eV), which correspond to the previous XRD, Raman, and XAS spectra. In Ti 2p core level spectra, there is a Ti3+ peak at 458.1 eV as well as the typical Ti4+ spectra of TiO2 at 459.4 eV. The ratio of Ti3+ peak to Ti4+ increases with the doping concentration, which is attributed to the oxygen-vacancy sites. When vacancies are generated, the oxidation state of the site is compensated by the nearest neighbor Ti through formation of Ti3+. This is also clearly evident from the pre-edge of the Ti L-edge and e g intensity of the O K-edge in the XAS spectra. Fe shows Fe3+ characteristics at 710.7 eV, which is also comparable with the previous results.

HRPES results for Fe 2p, Ti 2p, and O 1s core level spectra of Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles with various doping levels. a, d, g Core level spectra from 1 wt.% Fe@TiO2. b, e, h Those from 3 wt.% Fe@TiO2. c, f, i Those from 5 wt.% Fe@TiO2. HRPES results corresponding to the S 2p core level spectrum obtained after photocatalytic oxidation of 2-aminothiophenol on j 1, k 3, and l 5 wt.% Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles

Next, we determined the photocatalytic activities of each Fe@TiO2 nanoparticle by the oxidation of 2-ATP molecules. The surface-sensitive S 2p core level spectra were recorded using HRPES after 360 L of 2-ATP exposure in the presence of the same amount of oxygen under 365-nm UV light illumination. There are three distinct 2p 3/2 peaks at 161.5, 162.9, and 168.6 eV, which correspond to the C-SH unbounded state (denoted S1), bounded state (denoted S2), and sulfonic acid (SO3H) (denoted S3), respectively [30, 31]. Sulfonic acid was formed from the oxidation of thiol in 2-ATP. According to the S3 peaks of S 2p, sulfonic acid is increased as the concentration of Fe dopants in TiO2 increases. To confirm the effect of the energy of light and its photocatalytic performance, relative intensities were plotted as the ratio of S3 to S1 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5 shows the changes of relative intensity as a function of 2-ATP exposure under two different light sources. When UV (365 nm) is irradiated on the catalysts, photocatalytic activity increases by increase of Fe doping concentrates: 1 (0.15), 3 (0.29), and 5 wt.% (0.58). One significant observation is that photocatalytic oxidation is enhanced by increasing doping concentration under illumination in the visible range (540 nm). Otherwise, the ratio increased from 0.16 at 1 wt.% Fe to 0.73 at 5 wt.% of Fe, which shows significant increments compared to the intensity ratios under UV illumination. The phenomena arise from narrowing the TiO2 bandgap by doping and the heterojunction of Fe2O3 and TiO2 with high concentration.

Figure 6 and Additional file 1: Figure S5 (subtracted spectra by valence band of bare-TiO2) show the valence band spectra and changes with variations of the Fermi-edge. As shown in the valence band spectra (Fig. 6b), density of states arises at the valence band maximum and is expanded from 2.3 to 2.0 eV, and then to 1.4 eV, which indicates that the density of states lowers the bandgap significantly. There are two significant reasons for the bandgap reduction when the doping concentration is increased to 5 wt.%. One is the Fe3+ doping inside the TiO2, which generates the surface states as well as the oxygen-vacancy sites observed by XAS spectra with Ti3+ states on the HRPES spectra [32]. Those Ti3+, oxygen-vacancy couples introduce the dopant level inside the bandgap below the conduction band minimum and above the valence band maximum, respectively. Calculated density of states of anatase TiO2 with one oxygen vacancy per 16 oxygen atoms shows the similar Fermi-edge at below 2 eV [33]. And controllable Ti3+ shows the significant reduction the bandgap [34, 35]. The second reason is the precipitation as hematite Fe2O3, where the particles have a lower bandgap (2.1 eV) compared to TiO2 (3.2 eV) and promote bandgap narrowing by heterojunction between Fe2O3 and TiO2, enhancing the absorption of visible light [8, 26, 36]. From the mechanistic point of view, generated electrons after light absorption are trapped to the Ti3+ state below the conduction band minimum which facilitates the charge separation by using heterojunction. Those trapped electrons are transferred to O2 species with formation of Ti-O2 − binding as peroxide. Peroxide has been indicated as electron scavenger O2 species in the traditional photocatalytic oxidation on TiO2 [37, 38]. S 2p spectra of HRPES (Fig. 4) show the relatively large amount of bound state (S2) when the doping level is increased. This is caused by the dissociative adsorption of –SH group at the oxygen atom of TiO2 which triggers the decomposition of peroxide [39, 40]. Consequently, the amount of trapped electrons at the Ti3+ state captures and stabilizes the O2 then 2-ATP decomposes –SH to –S-O-Ti (bound state, S2), –OH on the peroxide. (Scheme 1) –SH group of 2-ATP can be activated by the transfer of hole from the valence band. The energy relaxation of –SH group is around 2 eV compared to bare TiO2 which makes electron deficient –SH group to facilitate the oxidation reaction with electron rich peroxide [41]. Surface Fe3+ sites play a role of stabilization of –OH by hydrogen bonding during reaction process [42, 43]. From those reasons, doping concentration at 3 and 5 wt.% shows the narrowed bandgap that absorbs the photons more efficiently under 540 nm visible light, thus resulting in the significant enhancement of photo-oxidation activity [44, 45].

Conclusions

In summary, Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized by sol-gel using a hydrothermal method. Their photocatalytic activity was characterized using surface spectroscopic measurements. According to the XRD, Raman, XAS, and HRPES spectra, Fe ions are successfully doped inside the anatase TiO2 substrate, and the crystal structure is changed to a distorted anatase-like structure that also has a hematite-Fe2O3 character as a Fe2O3 3TiO2 complex. These structural features form the lamellar structure in TEM images, which is attributed to the heterojunction between hematite Fe2O3 and anatase TiO2. Furthermore, the introduction of Fe3+ ions generates discrepancies in the oxidation state, which is compensated by the formation of oxygen vacancies and transforms to the surface [46]. These structural changes induce additional states at the edge of the conduction band and valence band, finally narrowing the bandgap. Moreover, the Ti3+ plays a role of electron trap to deliver the electrons to O2 species for oxidation reaction. As a result, photocatalytic oxidation activities of 2-ATP are significantly increased for both UV and visible photon energies.

References

Nakata K, Fujishima A (2012) TiO2 photocatalysis: design and applications. J Photochem Photobiol C 13:169–89

Ma Y, Wang X, Jia Y, Chen X, Han H, Li C (2014) Titanium dioxide-based nanomaterials for photocatalytic fuel generations. Chem Rev 114:9987–10043

Tryba B, Morawski AW, Inagaki M, Toyoda M (2006) The kinetics of phenol decomposition under UV irradiation with and without H2O2 on TiO2, Fe–TiO2 and Fe–C–TiO2 photocatalysts. Appl Catal B 63:215–21

Fujishima A, Zhang X, Tryk DA (2008) TiO2 photocatalysis and related surface phenomena. Surf Sci Rep 63:515–82

Lun Pang C, Lindsay R, Thornton G (2008) Chemical reactions on rutile TiO2 (110). Chem Soc Rev 37:2328–53

Nozik AJ, Miller J (2010) Introduction to solar photon conversion. Chem Rev 110:6443–45

Armaroli N, Balzani V (2007) The future of energy supply: challenges and opportunities. Angew Chem Int Ed 46:52–66

Malagutti AR, Mourão HAJL, Garbin JR, Ribeiro C (2009) Deposition of TiO2 and Ag:TiO2 thin films by the polymeric precursor method and their application in the photodegradation of textile dyes. Appl Catal B 90:205–12

Gil S, Garcia-Vargas J, Liotta L, Pantaleo G, Ousmane M, Retailleau L, Giroir-Fendler A (2015) Catalytic oxidation of propene over Pd catalysts supported on CeO2, TiO2, Al2O3 and M/Al2O3 oxides (M = Ce, Ti, Fe, Mn). Catalysts 5:671–89

Xiao L, Zhang J, Cong Y, Tian B, Chen F, Anpo M (2006) Synergistic effects of doped Fe3+ and deposited Au on improving the photocatalytic activity of TiO2. Catal Lett 111:207–11

Boccuzzi F, Chiorino A, Manzoli M, Lu P, Akita T, Ichikawa S, Haruta M (2001) Au/TiO2 nanosized samples: a catalytic, TEM, and FTIR study of the effect of calcination temperature on the CO oxidation. J Catal 202:256–67

Falconer JL, Magrini-Bair KA (1998) Photocatalytic and thermal catalytic oxidation of acetaldehyde on Pt/TiO2. J Catal 179:171–8

Li H, Bian Z, Zhu J, Huo Y, Li H, Lu Y (2007) Mesoporous Au/TiO2 nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic activity. J Am Chem Soc 129:4538–9

Narayana RL, Matheswaran M, Aziz AA, Saravanan P (2011) Photocatalytic decolourization of basic green dye by pure and Fe, Co doped TiO2 under daylight illumination. Desalination 269:249–53

Reddy JK, Lalitha K, Reddy PVL, Sadanandam G, Subrahmanyam M, Kumari VD (2013) Fe/TiO2: a visible light active photocatalyst for the continuous production of hydrogen from water splitting under solar irradiation. Catal Lett 144:340–6

Li J, Jacobs G, Das T, Davis BH (2002) Fischer–Tropsch synthesis: effect of water on the catalytic properties of a ruthenium promoted Co/TiO2 catalyst. Appl Catal A 233:255–62

Ohsaka T, Izumi F, Fujiki Y (1978) Raman spectrum of anatase, TiO2. J Raman Spectrosc 7:321–324

de Faria DLA, Venâncio Silva S, de Oliveira MT (1997) Raman microspectroscopy of some iron oxides and oxyhydroxides. J Raman Spectrosc 28:873–78

Fu X, Wang Y, Wei F (2009) Low temperature phase transition of ilmenite during oxidation by chlorine. Mater Trans 50:2073–8

Pownceby MI, Fisher-White MJ, Swamy V (2001) Phase relations in the system Fe2O3–Cr2O3–TiO2 between 1000 and 1300 °C and the stability of (Cr, Fe)2Tin − 2O2n − 1 crystallographic shear structure compounds. J Solid State Chem 161:45–56

Drofenik M, Golič L, Hanzel D, Kraševec V, Prodan A, Bakker M, Kolar D (1981) A new monoclinic phase in the Fe2O3.TiO2 system. I. Structure determination and Mössbauer spectroscopy. J Solid State Chem 40:47–51

Thomas AG, Flavell WR, Mallick AK, Kumarasinghe AR, Tsoutsou D, Khan N, Chatwin C, Rayner S, Smith GC, Stockbauer RL, Warren S, Johal TK, Patel S, Holland D, Taleb A, Wiame F (2007) Comparison of the electronic structure of anatase and rutile TiO2 single-crystal surfaces using resonant photoemission and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Phys Rev B 75:035105

Yan W, Sun Z, Pan Z, Liu Q, Yao T, Wu Z, Song C, Zeng F, Xie Y, Hu T, Wei S (2009) Oxygen vacancy effect on room-temperature ferromagnetism of rutile Co:TiO2 thin films. Appl Phys Lett 94:042508

Henderson GS, Liu X, Fleet ME (2002) A Ti L-edge X-ray absorption study of Ti-silicate glasses. Phys Chem Min 29:32–42

Wang D, Liu L, Sun X, Sham T-K (2015) Observation of lithiation-induced structural variations in TiO2 nanotube arrays by X-ray absorption fine structure. J Mater Chem A 3:412–9

Kareev M, Prosandeev S, Liu J, Gan C, Kareev A, Freeland JW, Xiao M, Chakhalian J (2008) Atomic control and characterization of surface defect states of TiO2 terminated SrTiO3 single crystals. Appl Phys Lett 93:061909

Shen S, Zhou J, Dong C-L, Hu Y, Tseng EN, Guo P, Guo L, Mao SS (2014) Surface engineered doping of hematite nanorod arrays for improved photoelectrochemical water splitting. Sci Rep 4:6627–35

Pollak M, Gautier M, Thromat N, Gota S, Mackrodt WC, Saunders VR (1995) An in-situ study of the surface phase transitions of α-Fe2O3 by X-ray absorption spectroscopy at the oxygen K edge. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res Sect B 97:383–6

Almeida TP, Kasama T, Muxworthy AR, Williams W, Nagy L, Hansen TW, Brown PD, Dunin-Borkowski RE (2014) Visualized effect of oxidation on magnetic recording fidelity in pseudo-single-domain magnetite particles. Nat Commun 5:5154–9

Okada T, Takeda Y, Watanabe N, Haeiwa T, Sakai T, Mishima S (2014) Chemically stable magnetic nanoparticles for metal adsorption and solid acid catalysis in aqueous media. J Mater Chem A 2:5751–8

Jeon E, Yang S, Kim Y, Kim N, Shin H-J, Baik J, Kim H, Lee H (2015) Comparative study of photocatalytic activities of hydrothermally grown ZnO nanorod on Si(001) wafer and FTO glass substrates. Nanoscale Res Lett 10:361

Zuo F, Wang L, Wu T, Zhang Z, Borchardt D, Feng P (2010) Self-Doped Ti3+ enhanced photocatalyst for hydrogen production under visible light. J Am Chem Soc 132:11856–7

Zuo F, Wang L, Feng P (2014) Self-doped Ti3+@TiO2 visible light photocatalyst: Influence of synthetic parameters on the H2 production activity. Int J Hydrogen Energy 39:711–7

Ren R, Wen Z, Cui S, Hou Y, Guo X, Chen J (2015) Controllable synthesis and tunable photocatalytic properties of Ti3+-doped TiO2. Sci Rep 5:10714

Xiong L-B, Li J-L, Yang B, Yu Y (2012) Ti3+ in the surface of titanium dioxide: generation, properties and photocatalytic application. J Nanomater 2012:1–13

Waterhouse GIN, Wahab AK, Al-Oufi M, Jovic V, Anjum DH, Sun-Waterhouse D, Llorca J, Idriss H (2013) Hydrogen production by tuning the photonic band gap with the electronic band gap of TiO2. Sci Rep 3:2849–53

Thomas AG, Syres KL (2012) Adsorption of organic molecules on rutile TiO2 and anatase TiO2 single crystal surfaces. Chem Soc Rev 41:4207–17

Lang X, Ma W, Chen C, Ji H, Zhao J (2014) Selective aerobic oxidation mediated by TiO2 photocatalysis. Acc Chem Res 47:355–63

Wang Q, Zhang M, Chen C, Ma W, Zhao J (2010) Photocatalytic aerobic oxidation of alcohols on TiO2: the acceleration effect of a brønsted acid. Angew Chem Int Ed 49:7976–9

Nakamura R, Imanishi A, Murakoshi K, Nakato Y (2003) In situ FTIR studies of primary intermediates of photocatalytic reactions on nanocrystalline TiO2 films in contact with aqueous solutions. J Am Chem Soc 125:7443–50

Wuister S, Donegá C, Meijerink A (2004) Influence of thiol capping on the exciton luminescence and decay kinetics of CdTe and CdSe quantum dots. J Phys Chem B 108:17393–7

Yan J, Zhang Y, Liu S, Wu G, Li L, Guan N (2015) Facile synthesis of an iron doped rutile TiO2 photocatalyst for enhanced visible-light-driven water oxidation. J Mater Chem A 3:21434–8

Popa M, Diamandescu L, Vasiliu F, Teodorescu C, Cosoveanu V, Baia M, Feder M, Baia L, Danciu V (2009) Synthesis, structural characterization, and photocatalytic properties of iron-doped TiO2 aerogels. J Mater Sci 44:358–64

Jun J, Dhayal M, Shin J-H, Kim J-C, Getoff N (2006) Surface properties and photoactivity of TiO2 treated with electron beam. Radiat Phys Chem 75:583–9

Lee H, Shin M, Lee M, Hwang YJ (2015) Photo-oxidation activities on Pd-doped TiO2 nanoparticles: critical PdO formation effect. Appl Catal B 165:20–6

Jug K, Nair NN, Bredow T (2005) Molecular dynamics investigation of oxygen vacancy diffusion in rutile. Phys Chem Chem Phys 7:2616–21

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (no. 20090083525 and no. 2015021156).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

YK participated in the overall experiments and wrote the manuscript. SY conducted STXM and TEM experiments. EJ and NK conducted STXM experiments. JB conducted HRPES experiments. HK and HL who are corresponding authors participated in the overall experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Supplementary material. Digital images and SEM images of Fe@TiO2 nanoparticles, XRD, and Raman intensity plot. Figure S1. Digital images of the Fe@TiO2 dispersed solution with several of Fe dopant concentration. Figure S2. SEM images as the morphologies varying the doping level of Fe: (a) 1 wt %, (b) 3 wt %, (c) 5 wt %; and their high-resolution images (a′), (b′), and (c′), respectively. Figure S3. EDX spectra with Fe peak (marked by black arrows) of big particles: (a) 1 wt% Fe@TiO2, (b) 3 wt% Fe@TiO2, and (c) 5 wt% Fe@TiO2. Figure S4. (a) XRD peak position and correspond lattice constant of (101) plane of anatase TiO2 structure and (b) Raman intensity ratio of I410 (α-Fe2O3 Eg) to I144 (anatase TiO2 Eg). Figure S5. Spectral subtraction of valence band spectra by bare TiO2 peak: (a) 1 wt% Fe@TiO2, (b) 3 wt% Fe@TiO2, and (c) 5 wt% Fe@TiO2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Yang, S., Jeon, E.H. et al. Enhancement of Photo-Oxidation Activities Depending on Structural Distortion of Fe-Doped TiO2 Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 41 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1263-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1263-6