Abstract

In this study, to fabricate a carbon free (C-free) air electrode, Co3O4 nanofibers were grown directly on a Ni mesh to obtain Co3O4 with a high surface area and good contact with the current collector (the Ni mesh). In Li-air cells, any C present in the air electrode promotes unwanted side reactions. Therefore, the air electrode composed of only Co3O4 nanofibers (i.e., C-free) was expected to suppress these side reactions, such as the decomposition of the electrolyte and formation of Li2CO3, which would in turn enhance the cyclic performance of the cell. As predicted, the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode successfully reduced the accumulation of reaction products during cycling, which was achieved through the suppression of unwanted side reactions. In addition, the cyclic performance of the Li-air cell was superior to that of a standard electrode composed of carbonaceous material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Recently, Li-air batteries have attracted much attention because of their potential as the next generation of battery systems; they provide higher energy densities than state-of-the-art Li-ion batteries [1–8]. However, the electrochemical performance of Li-air batteries is currently far from satisfactory for their commercialization to be viable. One of the major barriers to enhancing the performance of Li-air batteries is developing an air electrode that can offer a high capacity, low overpotential, and good cyclic performance. In non-aqueous Li-air cells, the basic reactions during the discharging and charging processes are the formation and decomposition of Li2O2, respectively, on the surface of the air electrode [9–15]. To obtain a reversible and sufficient capacity, the solid Li2O2 must be formed and stored on a conducting matrix with a high surface area. Hence, porous carbon, which has a high conductivity and surface area, has been recognized as one of the most attractive matrix materials for air electrodes. However, C promotes electrolyte decomposition during cycling, and it readily reacts with Li2O2 to form Li2CO3 [16–19]. These side reactions caused by the presence of C generate unwanted reaction products, such as Li2CO3 and organic materials, which are attributed to the decomposition of the electrolyte. While Li2O2, the ideal reaction product, is efficiently decomposed during the charging process, dissociating the unwanted reaction products is difficult, so they can be easily accumulated on the surface of the air electrode. This results in a high overpotential and limited cyclic performance [20, 21].

The use of C-free matrices in air electrodes is a possible solution for suppressing the formation of unwanted reaction products. Several research groups have already investigated C-free electrodes by using inorganic materials, such as TiC and Co3O4, which can also act as catalysts [22–24]. However, while these C-free electrodes exhibited enhanced cyclic performances, their capacities were relatively small (approximately 500 mAh⋅gelectrode −1) because inorganic matrices are heavy and have low surface areas. Therefore, to obtain C-free electrodes with high capacities, an optimum nanostructure with a high surface area must be fabricated.

In this study, we investigated Co3O4 nanofibers grown directly on the surface of a Ni mesh (the current-collector matrix) as a potential C- and binder-free air electrode. Co3O4 is considered a promising catalyst material for Li-air batteries [25–29], as well as a high-capacity anode material for Li-ion batteries [30–33]. The Co3O4 nanofibers, which acted as electron pathways, were strongly attached to the Ni mesh because they were grown directly on it. In addition, they had a high surface area, which offered sufficient space for the storage of Li2O2 and resulted in a high capacity of the air electrode. Moreover, the C- and binder-free structures were expected to suppress the unwanted side reactions related to the presence of C, which should enhance the electrochemical performance of the air electrode by increasing the cyclic performance.

Methods

A Ni mesh was used as the current collector and substrate. For the Co3O4 nanofiber seed solution, cobalt nitrate (Co(NO3)2⋅6H2O), ammonium fluoride (NH4F), and urea (CO(NH2)2) were dissolved in deionized water under stirring. The solution was then transferred to an autoclave. Polyimide tape was attached to the back of the Ni mesh to ensure the Co3O4 nanofibers only grew on the front of the mesh. The etched Ni mesh was then put into the seed solution. The hydrothermal reaction was performed at 95 °C for 8 h inside the autoclave. After the hydrothermal reaction, the sample was washed with deionized water and heat-treated at 350 °C for 2 h in an air atmosphere. To check the crystallinity of the Co3O4 nanofibers, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the air electrode was obtained with a Rigaku X-ray diffractometer equipped with a monochromatized Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5406 Å).

The Co3O4 nanofibers grown on the Ni mesh were then tested as the air electrode of a Li-air cell. For comparison purposes, an air electrode composed of Ketjen black (90 wt.%) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF, 10 wt.%) was prepared and tested, which will be referred to as the “standard electrode.” The loading mass of the Co3O4 nanofibers, and Ketjen black + PVDF was adjusted to be 0.5 ± 0.05 mg in both electrodes. Li metal and a glass fiber filter (GF/F, Whatman) were used as the anode and separator, respectively. A 1 M solution of lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide (LiTFSI) in tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether (TEGDME) was used as the electrolyte. The cells were assembled in an Ar-filled glove box. The electrochemical measurements were performed with Swagelok-type cells and a WonATech battery cycler (WBCs 3000) under an O2 atmosphere (1 atm) at 30 °C. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, AP Tech TECNAI G2 F30 STwin) was employed to observe the surface morphology of the electrodes during the cycling tests. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of the electrodes were collected with a JASCO FT-IR-4200 to ascertain the reaction products that accumulated on the electrodes during the cycling tests.

Results and Discussion

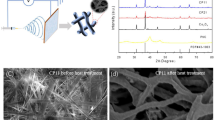

Figure 1 shows SEM images of the Co3O4 nanofibers grown on the Ni mesh and the standard electrode. Ketjen black is generally used as an electrode material in Li-air batteries [8, 13], hence its labeling as a “standard electrode.” Figure 1a shows that the standard electrode appears to be weakly attached to the surface of the Ni mesh, even though a considerable concentration of the PVDF binder was used (10 wt.%). If the electrode materials are prepared on the flat surface of a current collector (e.g., the electrodes of Li-ion batteries), they can be strongly attached to the current collector with various methods, including roll pressing. However, the air electrodes used in Li-air batteries should be prepared on current collectors with an open structure, such as meshes and fiber-like forms, which makes attaching the electrode material strongly to the surface of the current collector difficult. The weak attachment of an electrode material may lead to a poor long-term stability of that air electrode. Figure 1b, c shows that the surface of the standard electrode is composed of small circular particles, which must be the Ketjen black particles. In contrast, Fig. 1d–f shows that the Co3O4 nanofibers appear to be homogeneously distributed and strongly attached to the Ni mesh because they were directly grown on its surface. The shape of the nanofibers resembles that of grass, and they are approximately 1–3 μm long. These features may be favorable for supplementing the electrons of the Ni mesh that are used for the redox reactions between the Li ions and O2. While the electrical conductivity of the Co3O4 nanofibers may be poor, their strong attachment to the surface of the Ni mesh should compensate for it. Figure 2 shows the XRD pattern of the Co3O4 nanofibers grown on the Ni mesh. The crystalline peaks of the nanofibers can be indexed exactly to that of Co3O4 with a spinel structure, which confirms that crystalline Co3O4 was successfully formed on the surface of the Ni mesh.

The electrochemical performance of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode was characterized and compared to that of the standard electrode. Figure 3 shows the initial discharge–charge profiles of the standard and Co3O4-nanofiber electrodes. The current density and voltage range used for the measurements were 400 mA⋅g−1 and 2.35–4.35 V, respectively. The capacity values presented in this paper are based on the total electrode mass excluding the mass of the Ni mesh. The initial discharge capacity of the standard electrode is approximately 8500 mAh⋅g−1; however, its charge capacity is less than half of that. This relatively low charge capacity shows that some percentage of the reaction products formed during the discharge process are not sufficiently dissociated during the charge process. On the other hand, the initial discharge capacity of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode is approximately 2100 mAh⋅g−1. The discharge process ends when the reaction products, such as Li2O2, completely block the surface of the electrode, which stops any reaction between the Li ions and O2 from occurring on the electrode surface. Even though the Co3O4 was prepared in the form of nanofibers to achieve a high surface area and obtain enough space to store the reaction products, the discharge capacity per gram of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode is much lower than that of the standard electrode because of the higher mass of Co3O4. However, the charge capacity of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode is nearly identical to its discharge capacity, implying that the reaction products formed during the discharge process are effectively dissociated during the charge process. This also clearly shows that the catalytic activity of the Co3O4 nanofibers is superior to that of the Ketjen black, especially with respect to the O2 evolution reaction that occurs during the charging process.

Figure 4a shows the cyclic performance of the standard and Co3O4-nanofiber electrodes at a current density of 400 mA⋅g−1. They were cycled with a limited capacity of 800 mAh⋅gelectrode −1 to avoid a large depth of discharge [34]. The voltage range was 2.00–4.35 V, and the upper potential (4.35 V) was held until a current density of 2 mA⋅g−1 was reached during the charging process to facilitate the decomposition of the reaction products. Figure 4a shows that the standard electrode maintains its capacity for 72 cycles, while the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode maintains its capacity for all 120 cycles, indicating that the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode has a cyclic performance that is superior to that of the standard electrode. Considering that the limited capacity of our work (800 mAh⋅gelectrode −1) is higher than that of the previously reported C-free electrodes (approximately 500 mAh⋅gelectrode −1) [22–24], these results also show that the Co3O4 nanofibers have good catalytic activity and provide a relatively large storage area for the reaction products compared to other C-free electrodes.

Figure 4b, c shows the discharge–charge profiles of the standard and Co3O4-nanofiber electrodes, respectively. For both electrodes, as the number of cycles increases, the discharge profiles shift to lower voltages and the charge profiles shift to higher voltages, both of which result in an increase in the overpotential of the cells. However, the rate of increase in the overpotential of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode is much slower than that of the standard electrode. This enhanced cyclic performance of the Co3O4-nanofiber-based cell is attributed to the high catalytic activity of Co3O4 when C is not present, which allows the detrimental side reactions caused by carbonaceous materials to be avoided. Figure 5a shows that the Ketjen black in the standard electrode causes these unwanted side reactions, such as the decomposition of the electrolyte and formation of Li2CO3, which limit the cyclic performance of Li-air cells [16–20]. The relatively inferior cyclic performance of the standard electrode may be attributed to the accumulation of unwanted reaction products, which are formed through the side reactions on the surface of the air electrode during cycling. However, the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode suppresses these side reactions during cycling because it does not contain carbonaceous materials. Therefore, it reduces the accumulation of unwanted reaction products during cycling, which enhances the cyclic performance of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode, as shown in Fig. 5b.

To confirm this lack of unwanted reaction products in the C-free electrode composed of Co3O4 nanofibers, SEM images and FT-IR spectra of the standard and Co3O4-nanofiber electrodes were obtained. Figure 6 shows the SEM images of the electrodes after the first discharging and charging processes, and after 50 cycles (imaged in the charged state). The cycling conditions were the same as those used to obtain the results in Fig. 4a. Figure 6a shows the surface of the standard electrode after the first discharge process is covered with a film of reaction products. While most of these reaction products have dissociated after the first charging process (Fig. 6b), some are still present on the surface of the standard electrode. Figure 6c shows that the surface of the standard electrode is almost fully covered with reaction products after 50 cycles, even though it is in the charged state. This SEM image clearly indicates that the reaction products are not fully dissociated in the charged state and they are accumulated during cycling, which most likely causes the limited cyclic performance of standard electrodes composed of Ketjen black.

SEM images of the standard and Co3O4-nanofiber electrodes during cycling. a Standard electrode after the first discharging process. b Standard electrode after the first charging process. c Standard electrode after the 50th cycle (imaged in the charged state). d Co3O4-nanofiber electrode after the first discharging process. e Co3O4-nanofiber electrode after the first charging process. f Co3O4-nanofiber electrode after the 50th cycle (imaged in the charged state)

On the other hand, Fig. 6d shows that the surface of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode is also covered with a film of reaction products after the first discharging process. After the first charging process, the reaction products have clearly dissociated (Fig. 6e). Moreover, the surface of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode after 50 cycles is very clear (Fig. 6f). The surface morphology of the standard electrode is very different after the 1st and 50th cycles, as shown in Fig. 6b, c. In contrast, the surface morphology of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode after 50 cycles is very similar to that after the first cycle, as shown in Fig. 6e, f. These results clearly confirm that the C-free Co3O4-nanofiber electrode successfully suppresses the accumulation of unwanted reaction products during cycling.

To characterize the reaction products formed during cycling, FT-IR spectra of the electrodes were collected after the first discharging and charging processes and after 50 cycles (obtained in the charged state). In the spectrum obtained after discharging the standard electrode (Fig. 7a), there are broad peaks between 400 and 600 cm−1 that are attributed to the formation of Li2O2. The broad peaks between 1400 and 1600 cm−1 and the sharp peak at approximately 870 cm−1 can be attributed to Li2O2 that has been exposed to air. After the first charging process, the large peaks have mostly vanished apart from some small, broad peaks between 1100 and 1800 cm−1, which can be attributed to the presence of Li2CO3. After 50 cycles, several large peaks are present in the FT-IR spectrum. The peaks at 400–500 cm−1, 550–700 cm−1, 1350–1500 cm−1, and 1500–1700 cm−1 (marked with ♦ symbols) can be attributed to organic compounds, such as CH3CO2Li and HCO2Li (both of which have similar FT-IR spectra). Li2CO3 may still be present on the electrode after 50 cycles, but confirming its existence was difficult because the major FT-IR peaks of Li2CO3 are overlapped by the large peaks of the organic materials and Li2O2. However, a large amount of unwanted reaction products have been formed through side reactions and subsequently accumulated on the standard electrode surface during the 50 cycles, which is in good agreement with the SEM image shown in Fig. 6c. The FT-IR spectrum of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode after the first discharging process has peaks corresponding to Li2O2, which vanish after the first charging process (Fig. 7b). These results are similar to that of the standard electrode. However, the spectrum of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode after the 50th cycle is almost identical to that obtained after the 1st cycle, with no large peaks related to organic materials and Li2CO3 present. Compared to the spectrum of the standard electrode after 50 cycles (Fig. 7a), the spectrum of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode clearly confirms that it has effectively reduced the accumulation of unwanted reaction products. In addition, by considering that the unwanted reaction products formed through side reactions are easily accumulated because they are hard to dissociate during the charging process [1, 2, 6, 7], the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode has clearly suppressed the detrimental side reactions. Therefore, we can conclude that the superior cyclic performance of the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode results from the suppression of unwanted side reactions. C-free air electrodes composed of catalytic materials, including Co3O4, may have a low discharge capacity because of the high mass of such materials. However, if the surface area of the catalytic material is increased through various approaches, C-free air electrodes appear to be promising candidates for Li-air cells because they have better cyclic performances than that of general air electrodes composed of carbonaceous materials.

Conclusions

In this study, Co3O4 nanofibers were successfully grown on the surface of a Ni mesh and they were tested as the air electrode of a Li-air cell. The Co3O4 nanofibers were strongly attached to the Ni mesh and provided a high surface area for the storage of reaction products. While the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode exhibited a smaller discharge capacity than that of a standard electrode composed of Ketjen black, it demonstrated a superior cyclic performance. Compared to the standard electrode, the Co3O4-nanofiber electrode effectively reduced the accumulation of unwanted reaction products during cycling, as confirmed with both SEM and FT-IR analyses. The Co3O4-nanofiber electrode did not contain any carbonaceous materials that could promote side reactions, such as the decomposition of the electrolyte and formation of Li2CO3. Therefore, Co3O4-nanofiber electrodes can limit the unwanted side reactions during cycling, which improves the cyclic performance of such electrodes.

References

Cheng F, Chen J. Metal-air batteries: oxygen reduction electrochemistry to cathode catalysts. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2172.

Luntz AC, McCloskey BD. Nonaqueous Li-Air batteries: a status report. Chem Rev. 2014;114:11721.

Ryu WH, Yoon TH, Song SH, Jeon S, Park YJ, Kim ID. Bifunctional composite catalysts using Co3O4 nanofibers immobilized on nonoxidized grapheme nanoflakes for high-capacity and long-cycle Li-O2 batteries. Nano Lett. 2012;13:4190.

Li F, Zhang T, Zhou H. Challenges of non-aqueous Li-O2 batteries: electrolytes, catalysts, and anodes. Energy Environ Sci. 2013;6:1125.

Yoon TH, Park YJ. New strategy toward enhanced air electrode for Li–air batteries: apply a polydopamine coating and dissolved catalyst. RSC Adv. 2014;4:17434.

Black R, Adams B, Nazar LF. Non-aqueous and hybrid Li-O2 batteries. Adv Energy Mater. 2014;2:801.

Christensen J, Albertus P, Sanchez-Carrera RS, Lohmann T, Kozinsky B, Liedtke R, et al. A critical review of Li/Air batteries. J Electrochem Soc. 2012;159:R1.

Kim DS, Park YJ. Effect of multi-catalysts on rechargeable Li–air batteries. J Alloys Compd. 2014;591:164.

Bruce PG, Freunberger SA, Hardwick LJ, Tarascon JM. Li–O2 and Li–S batteries with high energy storage. Nat Mater. 2012;11:19.

Padbury R, Zhang X. Lithium–oxygen batteries—limiting factors that affect performance. J Power Sources. 2011;196:4436.

Kraytsberg A, Ein-Eli Y. Review on Li–air batteries—opportunities, limitations and perspective. J Power Sources. 2011;196:886.

Lee CK, Park YJ. Polyimide-wrapped carbon nanotube electrodes for long cycle Li–air batteries. Chem Commun. 2015;51:1210.

Park CS, Kim KS, Park YJ. Carbon-sphere/Co3O4 nanocomposite catalysts for effective air electrode in Li/air batteries. J Power Sources. 2013;244:72.

Lee JS, Kim ST, Cao R, Choi NS, Liu M, Lee KT, et al. Metal–air batteries with high energy density: Li–air versus Zn–air. Adv Energy Mater. 2011;1:34.

Kim DS, Park YJ. Buckypaper electrode containing carbon nanofiber/Co3O4 composite for enhanced lithium air batteries. Solid State Ionics. 2014;268:216.

McCloskey BD, Speidel A, Scheffler R, Miller DC, Viswanathan V, Hummelshøj JS, et al. Twin problems of interfacial carbonate formation in nonaqueous Li–O2 batteries. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:997.

Lu J, Lei Y, Lau KC, Luo X, Du P, Wen J, et al. A nanostructured cathode architecture for low charge overpotential in lithium-oxygen batteries. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2383.

Thotiyl MMO, Freunberger SA, Peng Z, Bruce PG. The carbon electrode in nonaqueous Li-O2 cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:494.

Kim H, Lim HD, Kim J, Kang K. Graphene for advanced Li/S and Li/air batteries. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2:33.

Gallant BM, Mitchell RR, Kwabi DG, Zhou J, Zuin L, Thompson CV, et al. Chemical and morphological changes of Li–O2 battery electrodes upon cycling. J Phys Chem C. 2012;116:20800.

Lu YC, Shao-Horn Y. Probing the reaction kinetics of the charge reactions of nonaqueous Li–O2 batteries. J Phys Chem Lett. 2013;4:93.

Cui Y, Wen Z, Liu Y. A free-standing-type design for cathodes of rechargeable Li–O2 batteries. Energy Environ Sci. 2011;4:4727.

Thotiyl MMO, Freunberger SA, Peng Z, Chen Y, Liu Z, Bruce PG. A stable cathode for the aprotic Li–O2 battery. Nat Mater. 2013;12:1050.

Riaz A, Jung KN, Chang W, Lee SB, Lim TH, Park SJ, et al. Carbon-free cobalt oxide cathodes with tunable nanoarchitectures for rechargeable lithium–oxygen batteries. Chem Commun. 2013;49:5984.

Sun C, Li F, Ma C, Wang Y, Ren Y, Yang W, et al. Graphene–Co3O4 nanocomposite as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for lithium–air batteries. J Mater Chem A. 2014;2:7188.

Yoon TH, Park YJ. Polydopamine-assisted carbon nanotubes/Co3O4 composites for rechargeable Li-air batteries. J Power Sources. 2013;244:344.

Yang W, Salim J, Ma C, Ma Z, Sun C, Li J, et al. Flowerlike Co3O4 microspheres loaded with copper nanoparticle as an efficient bifunctional catalyst for lithium–air batteries. Electrochem Commun. 2013;28:13.

Lim HD, Gwon H, Kim H, Kim SW, Yoon T, Choi JW, et al. Mechanism of Co3O4/graphene catalytic activity in Li–O2 batteries using carbonate based electrolytes. Electrochimica Acta. 2013;90:63.

Kim DS, Park YJ. Ketjen black/Co3O4 nanocomposite prepared using polydopamine pre-coating layer as a reaction agent: effective catalyst for air electrodes of Li/air batteries. J Alloys Compd. 2013;575:319.

Yu L, Shen Y, Huang Y. Fe-N-C catalyst modified graphene sponge as a cathode material for lithium-oxygen battery. J Alloys Compd. 2014;595:185.

Tao L, Shengjun L, Bowen Z, Bei W, Dayong N, Zeng C, et al. Supercapacitor electrode with a homogeneously Co3O4-coated multiwalled carbon nanotube for a high capacitance. Nanoscale Research Lett. 2015;10:208.

Yoon TH, Park YJ. Electrochemical properties of CNTs/Co3O4 blended-anode for rechargeable lithium batteries. Solid State Ionics. 2012;225:498–501.

Huang Z, Zhang M, Cheng J, Gong Y, Li X, Chi B, et al. Silver decorated beta-manganese oxide nanorods as an effective cathode electrocatalyst for rechargeable lithium–oxygen battery. J Alloys Compd. 2015;626:173.

Débart A, Paterson AJ, Bao J, Bruce PG. α-MnO2 nanowires: a catalyst for the O2 electrode in rechargeable lithium batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4521.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (No. 2014R1A2A2A01003542) and by the Energy Efficiency & Resources Core Technology Program of the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), granted financial resource from the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy, Republic of Korea. (No. 20112020100110/KIER KIER B5-2592).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

CKL performed the synthesis and characterization in this study. YJP gave advice and guided the experiment. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, C.K., Park, Y.J. Carbon and Binder-Free Air Electrodes Composed of Co3O4 Nanofibers for Li-Air Batteries with Enhanced Cyclic Performance. Nanoscale Res Lett 10, 319 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1027-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1027-8