Abstract

Different stages of intrinsic nanostructurization related to evolution of free-volume voids, including phase separation, crystalline nuclei precipitation, and growth, were studied in glassy As2Se3 doped with Ga up to 5 at. %, using complementary techniques of positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy, X-ray powder diffraction, and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis. Positron lifetime spectra reconstructed in terms of a two-state trapping model testified in favor of a native void structure of g-As2Se3 modified by Ga additions. Under small Ga content (below 3 at. %), the positron trapping in glassy alloys was dominated by voids associated with bond-free solid angles of bridging As2Se4/2 units. This void agglomeration trend was changed on fragmentation with further Ga doping due to crystalline Ga2Se3 nuclei precipitation and growth, these changes being activated by employing free volume from just attached As-rich glassy matrix with higher content of As2Se4/2 clusters. Respectively, the positron trapping on free-volume voids related to pyramidal AsSe3/2 units (like in parent As2Se3 glass) was in obvious preference in such glassy crystalline alloys.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ga-modified chalcogenide glasses (ChG) are known to be of high importance in view of their perspectives for modern IR photonics as active media with improved optical functionality, revealed, in part, when these glasses are doped with rare earth (RE) activators such as Pr3+, Dy3+, Tb3+, Er3+, and Nd3+ [1–9]. Such ChG demonstrates an obvious tendency to nanostructurization by forming intrinsic inhomogeneities because of strong Ga affinity to chemical interaction with chalcogens, this process being governed by Ga content and preferential type of its environment in parent glass matrix [4, 10–16]. In dependence on these pre-requisites, extra Ga additions can result in phase separation, nucleation and, finally, crystal growth, leading to stabilization of different crystalline Ga2Se3 polymorphs. Thus, under small Ga content (2–3 at. %) added in mixed Se–Te environment of TAS-235 glass (e.g., glassy g-As30Se50Te20 alloy), the nanoscale droplets of dominated γ-Ga2Se3 phase (a few hundreds of nanometers in sizes) can be displayed, while at more enhanced Ga content reaching 5–10 at. %, this process extends over a microscale, when these crystallites grow to a few micrometers in sizes [8, 13]. In contrast, in Se-rich environment of Ge-based GeSe2–Ga2Se3 glass at heat treatment not too far above T g , these Ga additions provoke formation of some multication crystallites like GeGa4Se8 [14–16] or Ga2−δGeδSe3 [12]. Crystallite growth and stabilization in ChG matrices is accompanied by complicated changes stretching over both atomistic (atomic-specific) and void (atomic-deficient) structural levels. The latter is related to the evolution of some free-volume entities (typically sub-nanoscale voids, vacancies, vacancy-like clusters, etc.), when inner holes are agglomerated to form spaces of reduced electron density available for orientation stabilization of growing crystallites or, conversely, these holes are fragmented on smaller parts ensuring energetically favorable localization for growing crystallites in a predominantly glass environment [13]. In case of technologically controlled crystallization, it is possible to manufacture an important class of glass ceramics transparent in IR region, which possess much better mechanical reliability than their glassy counterparts [17]. But in most cases, these crystallization processes are undesirable, especially when ChG should be doped with RE ions to get tunable, high-power, secondary remote mid-IR sources [9], or drawn into fiber to produce active media for optical biosensing [18].

In this work, the physical peculiarities of Ga-affected nanostructurization associated with subsequent stages of glass structure modification (phase separation, nucleation, and crystallization), overall described at atomic-deficient void level, are comprehensively studied in g-As2Se3, one of the well-known canonical representatives of functional chalcogenide photonics [19].

Methods

The studied samples of Ga x (As0.4Se0.6)100−x (x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) alloys were prepared from high-purity elemental constituents (5 N or more) by conventional melt-quenching technique as described elsewhere [9, 11]. Total weight of ingredients inserted in silica ampoules of 10 mm in diameter used for melting was 30 g. The ampoule was sealed under a vacuum and heated at 900 °C in a rocking furnace for 10 h, followed by quenching into room temperature water from 700 °C. Then, these alloys were annealed during 5 h at 10 K below glass transition to remove mechanical strains that appeared during quenching, cut into disks of ~2 mm in thickness, and finally, polished to high optical quality.

The crystalline state of the samples was controlled with X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD), experimental data being collected in the transmission mode on a STOE STADI P diffractometer (Cu Kα1-radiation). The crystal structures of phases were refined by the Rietveld method with the program FullProf.2k (v. 5.40) [20]. The surface morphology of fresh cut sections of the prepared alloys was tested using scanning electron microscope (SEM) with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analyzer FEI QUANTA 3D 200i (Hillsboro, OR, USA).

Positron annihilation lifetime (PAL) spectra were registered using fast coincidence system ORTEC of 230 ps resolution (the full width at half maximum) operated at high-stabilized normal measuring conditions. The pair of identical plane-parallel samples of each composition in sandwich geometry was employed for the measurements. The source contribution from 22Na isotope of low activity was taken at the level of 12 % (τ = 0.372 ns). To ensure reliable PAL data, three independent measuring cycles (with near 1 M elementary positron annihilation events) were performed. Experimental results were fitted by two single exponents under normalized intensities (I 1 + I 2 = 1) using LT 9.0 program [21], the corresponding accuracies in lifetimes τ i and intensities I i being not worse ±0.005 ns and 0.5 %, respectively. Mathematical formalism of the known two-state positron trapping model with only one kind of traps [22–26] was utilized to parameterize mean τ av and defect-free bulk τ b lifetimes, as well as trapping rate in defects κ d. In addition, the difference between defect-related τ d = τ 2 and bulk positron lifetimes (τ 2−τ b) was taken as a signature of size of positron traps in terms of equivalent number of vacancies, and τ 2/τ b ratio was ascribed to nature of these defects [22]. The fraction of trapped positrons η = τ 1⋅κ d was also controlled in this research.

Results and Discussion

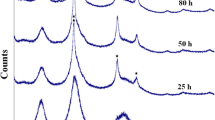

Different stages of intrinsic nanostructurization can be activated in g-As2Se3 in dependence on the amount of added Ga [9, 11]. Firstly, at small enough Ga content within studied Ga x (As0.4Se0.6)100−x cut section not exceeding 3 at. %, the melt-quenched alloys are fully in a glassy state, since no any sharp reflexes (but only wide-stretched halos typical for amorphous substances) are detected on the XRPD patterns [9]. Further, at higher Ga content, some crystallites of low-temperature α-Ga2Se3 phase appear in glassy crystalline g/c-Ga4(As0.4Se0.6)96 alloy, the crystallized phase being well identified due to six sharp XRPD peaks corresponding to one of cubic Ga2Se3 polymorphs with a space group of \( F\overline{4}3m \) (JCPDS ICDD card no. 89-7201) [9, 27–29]. The most pronounced crystallization effect is revealed in g/c-Ga5(As0.4Se0.6)95, where ten separate XRPD peaks centered near 28.5°, 33°, 47°, 56°, 69°, 76°, 87.5°, 94.5°, 106°, and 113° 2Θ are detected (Fig. 1). These peaks can be well indexed assuming fcc Ga2Se3 structure of zinc blende type (\( F\overline{4}3m \) space group), which allow to estimate the unit cell lattice parameter a = 5.4576(6) Å (with respective unit cell volume V = 162.55(3) Å3). In accord with similar behavior in Ga-doped g-As30Se50Te20 [8, 13], this effect can be ascribed to preferential formation of high-temperature γ-Ga2Se3 phase.

Under this Ga content, the crystallization is most evident, the cones of four to six separate Ga2Se3 crystallites (each less than 1 μm) being well distinguished at cut surface of g/c-Ga5(As0.4Se0.6)95 alloys (Fig. 2). The chemical composition of the sample was checked in two different spots, these being uniform surface area without visible inclusions (A) and one with some agglomerated crystallites (B). The corresponding EDS spectra from these spots detected up to 15 keV (current 0.65 nA) are shown in Fig. 3. Only arsenic As, selenium Se, and gallium Ga were defined as main elements responsible for the observed peaks on these spectra, located respectively to their Lα and Kα states. Despite uncertainties due to large scatter in the experimental points, a sharp increase in Ga and decrease in As content was detected from a crystallite-covered area. In opposite, the uniform sample matrix near crystallites was enriched on As and deficient on Ga, while Se content was nearly the same over a whole sample’s surface. These results testify that extraction of Ga2Se3 phase is indeed the most plausible reason for growing crystallites.

The above processes essentially modify atomic-deficient void structure of Ga x (As0.4Se0.6)100−x alloys, as it follows from PAL spectra reconstructed within the two-component fitting procedure (Fig. 4) and best-fit positron trapping parameters gathered in Table 1. Since neither average τ av nor defect-free bulk τ b positron lifetimes are changed under Ga additions, the two-state trapping model based on one preferential type of positron traps [22–26] can be validated as most relevant to the physically realistic channel of positron annihilation in these alloys. The volumes of these traps (e.g., sizes of low-electron density spaces) in g or g/c alloys are reflected by defect-related τ 2 lifetimes, while their contents being proportional to intensities of the second fitting components (I 2) [22]. Thus, the positron trapping modes correspondingly recalculated in respect to the above fitting parameters, including trapping rate in defects κ d, (τ 2−τ b) difference, τ 2/τ b ratio, and fraction of trapped positrons η, can be ascribed to the same type of traps as those characteristic for g-As2Se3 [23, 30–33], which are subjected to Ga-activated compositional modification within the Ga x (As0.4Se0.6)100−x system.

In g-As2Se3, the positron trapping is defined by spatial distribution of low-electron density spaces (native free-volume voids) formed within cycle-type formations of chalcogen-interlinked polyhedrons, such as AsSe3/2 pyramids (the fractional subscript means atoms simultaneously belonging to two neighboring units) [23, 31]. Despite deviation in the number of elements forming such cycle-type formations in a glass, they can be considered as network remainders of strict 12-membered cycles in a crystalline structure of rhombohedral As2Se3 [34]. In void structure evolution in ChG, an essential role belongs to spaces in the nearest atomic surrounding, which are free of electron density due to directionality of covalent bonds, e.g., bond-free solid angles (BFSA) in terms of Kastner [35]. Depending on electronegativity of neighbors [36], these intrinsic local spaces can be associated with effective neutral (Se atoms in –Se–Se–Se– chain- and ring-like fragments), positive (As atoms in the top of AsSe3/2 pyramids), or negative (Se atoms within heteronuclear =As–Se–As= bridges, e.g., in the bottom of neighboring AsSe3/2 pyramids) electrical charge [23, 31, 37]. So the most efficient positron traps in a covalent-bonded network of g-As2Se3 represent geometrical free-volume spaces within corresponding cycle-type formations of interlinked AsSe3/2 pyramids (atomic-accessible void core) surrounded by low-electron density spaces originated from atomic environment due to strict directionality of covalent chemical bonds (atomic-inaccessible void shell). The possible configurations of some void shells (e.g., BFSA) in ChG systems are considered in more detail elsewhere [23, 37, 38]. If only geometrical free volumes (void cores) have been decisive in a positron trapping in ChG, then defect-related positron lifetime τ 2 would be in strong correlation with molar volume in a g-As–Se system. However, an obviously opposite tendency is observed in g-As–Se, e.g., increase in τ 2 positron lifetime with going from looser Se-rich towards stoichiometric As2Se3 and As-rich glasses [31], thus meaning an importance of contribution from agglomerated BFSA (void shells) surrounding geometrical voids. From a standpoint of positron trapping [22], the heteroatomic environment around a chalcogen atom has an obvious preference. Indeed, because of difference in the electronegativity [36], such low-electron density sites carry an effective negative charge, thus transforming corresponding free-volume void in a prototype of cation vacancy in a crystal. This local electrical charge distribution is not characteristic of pure homoatomic Se chains or rings, resulting in reduced positron trapping in Se-rich ChG [31, 32].

In the network of Se-interlinked AsSe3/2 pyramids forming the structure of g-As2Se3, two of three Se atoms in the bottom of the AsSe3/2 pyramid contribute with their BFSA towards free-volume void, while the third Se atom contradicts this because of electron density cone of a covalent bond directed in an opposite hemisphere as void. The geometrically optimized configuration of such AsSe3/2 pyramidal cluster computed with ab initio quantum chemical modeling [39] is shown in Fig. 5. Thus, the most expected positron traps in g-As2Se3 can be imagined as free-volume voids surrounded by neighboring BFSA originated from two Se atoms (in heteroatomic =As–Se–As= environment) of the AsSe3/2 pyramid. The expected volumes of such positron traps (near ~90 Å3) can be simply estimated from corresponding defect-related positron lifetime τ 2 ≅ 0.36 ns in respect to Jensen’s calculations [33]. Possible configuration of such void in orpiment As2S3 crystal, the known crystalline counterpart of As2Se3 [34], reproduced in respect to electronic structure calculations for mineral arsenic sulfide As2S3 performed using Exciting package [40] is depicted in Fig. 6. Undoubtedly, such voids remain in melt-quenched state, thus defining preferential positron trapping in ChG, while voids surrounded by As-based BFSA are rather ineffective for trapping because of repulsive potential for positrons [31, 32]. With transition to over-stoichiometric As-rich ChG, the bridging As2Se4/2 units based on homopolar As–As bonds appear in a network of AsSe3/2 pyramids. Both pairs of Se atoms at the edges of the As–As bond contribute fully to free-volume void, since their BFSA are directed to one hemisphere without any restrictions on opposite directionality of Se atoms like in AsSe3/2 units (see Fig. 5). So the volumes of such voids grow (in full harmony with decreased atomic densities [34]), thus resulting in enhanced defect-related τ 2 lifetimes for ChG consisting of these structural units, while their concentration (reflected in I 2 intensity) essentially drops in view of chemical formulation [23, 41].

Geometrically optimized configurations of some atomic clusters in g-As-Se computed by ab initio quantum chemical modeling with RHF/6-311G* basis set [39]. a AsSe3/2 pyramid (two of three Se atoms contribute with their BFSA to one hemisphere). b As2Se4/2 bridge (all four Se atoms contribute with their BFSA to one hemisphere)

Electron density distribution in mineral As2S3 orpiment visualized with Exciting package [40]: unit cell is along [100] with two isosurface levels of electron localization function (ELF = 0.676, 0.338); the boundaries of free-volume void evolving core and surrounding shell are dark-distinguished

This effect is dominated in g-As2Se3 at small Ga addition, specifically in g-Ga1(As0.4Se0.6)99 and g-Ga2(As0.4Se0.6)98, where increase in τ 2 lifetime from 0.360 to 0.382 ns (Table 1) is caused by transition to positron trapping on free-volume voids neighboring with Se-type BFSA of As2Se4/2 units. The bridging As2Se4/2 clusters appear due to deficit in Se environment for As atoms because of Ga doping at small concentration. Indeed, chemical interaction in a Ga–As–Se system is governed by Ga bonding. By accepting energies for homonuclear Ga–Ga, As–As, and Se–Se bonds as 34.1, 32.1, and 44.0 kcal/mol, respectively [36, 42], the energies for heteronuclear Ga–Se, Ga–As, and As–Se bonds can be estimated in respect to known Pauling’s formula [36] as 55.2, 37.2, and 41.7 kcal/mol, respectively. Thereby, the Ga dopants form polyhedra with Se atoms inserted in remainder of the As–Se network [8–11, 43, 44]. Because of higher atomic packing of Ga-doped ChG [8–11], this trend is accompanied by reduced second-component I 2 intensity, trapping rate in defects κ d, and fraction of trapped positrons η in addition to enlarged τ 2 lifetime, (τ 2−τ b) difference, and τ 2/τ b ratio (Table 1).

Another g-Ga3(As0.4Se0.6)97 alloy, possessing positron trapping modes which are rather close to the ones of g-As2Se3 (Table 1), is obviously exceptional from the above correlation line. Defect-related annihilation channel in this ChG is presumably distorted due to crystalline nuclei precipitation of separated Ga2Se3 phase, like it occurred in 80GeSe2–20Ga2Se3 glass under thermally induced “cold” crystallization [16]. At this stage, the Ga2Se3 crystallites do not grow enough to be detected quite reliably with XRPD. The nuclei precipitation process is activated by employing free volume of just attached As-rich matrix with preferential content of bridging As2Se4/2 clusters. Correspondingly, the defect-related τ 2 lifetime drops down to the value of ~0.36 ns, which is characteristic of positron trapping on free-volume voids within AsSe3/2-based cycle formations in stoichiometric g-As2Se3 (see Table 1).

This process is continued in g/c-Ga4(As0.4Se0.6)96 and g/c-Ga5(As0.4Se0.6)95 alloys due to further growth and precipitation of Ga2Se3 crystallites, which became XRPD-detectable at these conditions (Fig. 1). These crystallites are restricted in their growing in Se-deficient environment, thus being stabilized in the ChG by utilizing atomic-accessible free volumes of their nearest environment rich in As2Se4/2 clusters. In such alloys, the positron trapping on free-volume entities built of pyramidal AsSe3/2 units has an obvious preference, tending the overall annihilation-like void fragmentation without notable changes in sizes of positron traps (τ 2 = ~0.36 ns) and enhanced second-component intensities I 2, in full respect to the experimental data in Table 1.

Conclusions

The nanostructurization processes related to evolution of free-volume voids were studied in glassy As2Se3 affected by different amounts of Ga additions (up to 5 at. %), using positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy, the lifetime spectra being analyzed within a canonical two-component model with one preferential type of positron traps. It was shown that below 3 at. % of Ga, when glass formation was not essentially violated, the positron trapping is dominated on intrinsic voids associated with bond-free solid angles of bridging As2Se4/2 units, thus producing an increase in defect-related lifetime from 0.360 to 0.382 ns at the cost of reduced second-component intensity and positron trapping rate in defects. This void agglomeration trend was changed on opposite (void fragmentation) at greater Ga content in As2Se3 glass due to crystalline Ga2Se3 nuclei precipitation and growth. The observed crystallization processes were activated by employing free volume of just attached As-rich matrix with higher content of As2Se4/2 clusters. In such glassy crystalline alloys, the positron trapping on free-volume entities related to pyramidal AsSe3/2 units (as in parent As2Se3 glass) was in obvious preference, tending overall annihilation-like void fragmentation without notable changes in sizes of positron traps.

Abbreviations

- BFSA:

-

bond-free solid angle

- ChG:

-

chalcogenide glass

- EDS:

-

energy-dispersive spectroscopy

- PAL:

-

positron annihilation lifetime

- RE:

-

rare earth

- SEM:

-

scanning electron microscope

- XRPD:

-

X-ray powder diffraction

References

Cole B, Shaw LB, Pureza PC, Mossadegh R, Sanghera JS, Aggarwal ID (1999) Rare-earth doped selenide glasses and fibers for active applications in the near and mid-IR. J Non-Cryst Solids 256–257:253–259

Lezal D (2003) Chalcogenide glasses. J Optoelectron Adv Mater 5:23–34

Choi YG (2007) Spatial distribution of rare-earth ions in Se-based chalcogenide glasses with or without Ga. J Non-Cryst Solids 353(18–21):1930–1935

Seddon AB, Tang Z, Furniss D, Sujecki S, Benson TM (2010) Progress in rare earth-doped mid-infrared fiber lasers. Opt Express 18(25):26704–26719

Charpentier F, Starecki F, Doualan JL, Jóvári P, Camy P, Troles J, Belin S, Bureau B, Nazabal V (2013) Mid-IR luminescence of Dy3+ and Pr3+ doped Ga5Ge20Sb10S(Se)65 bulk glasses and fibers. Mater Lett 101:21–24

Starecki F, Charpentier F, Doualan JL, Quetel L, Michel K, Chahal R, Troles J, Bureau B, Braud A, Camy P, Moizan V, Nazabal V (2015) Mid-IR optical sensor for CO2 detection based on fluorescence absorbance of Dy3+:Ga5Ge20Sb10S65 fibers. Sens Actuators, B 207:518–525

Pelé AL, Braud A, Doualan JL, Chahal R, Nazabal V, Boussard-Plédel C, Bureau B, Moncorgé R, Camy P (2015) Wavelength conversion in Er3+ doped chalcogenide fibers for optical gas sensors. Opt Express 23(4):4163–4172

Ya S, Bureau B, Boussard C, Nazabal V, Golovchak R, Demchenko P, Polovynko I (2014) Effect of Ga incorporation in the As30Se50Te20 glass. J Non-Cryst Solids 398–399:19–25

Ya S, Boussard-Pledel C, Nazabal V, Chahal R, Ari J, Pavlyk B, Cebulski J, Doualan JL, Bureau B (2015) Ga-modified As2Se3-Te glasses for active applications in IR photonics. Opt Mater 46:228–232

Golovchak R, Shpotyuk Y, Nazabal V, Boussard-Pledel C, Bureau B, Cebulski J, Jain H (2015) Study of Ga incorporation in glassy arsenic selenides by high-resolution XPS and EXAFS. J Chem Phys 142(18):184501-1-10

Golovchak R, Shpotyuk Y, Thomas CM, Nazabal V, Boussard-Pledel C, Bureau B, Jain H (2015) Peculiarities of Ga and Te incorporation in glassy arsenic selenides. J Non-Cryst Solids 429:104–111

Liu C, Tang G, Luo L, Chen W (2009) Phase separation inducing controlled crystallization of GeSe2-Ga2Se3-CsCl glasses for fabricating infrared transmitting glass-ceramics. J Am Ceram Soc 92(1):245–248

Shpotyuk O, Ingram A, Bureau B, Shpotyuk Y, Boussard C, Nazabal V, Szatanik R (2014) Positron annihilation probing of crystallization effects in TAS-235 glass affected by Ga additions. J Phys Chem Solids 75(9):1049–1053

Roze M, Calvez L, Ledemi Y, Allix M, Matzen G, Zhang X (2008) Optical and mechanical properties of glasses and glass–ceramics based on the Ge–Ga–Se system. J Amer Ceram Soc 91(11):3566–3570

Golovchak R, Calvez L, Petracovschi E, Bureau B, Savytskii D, Jain H (2013) Incorporation of Ga into the structure of Ge-Se. Mater Chem Phys 138:909–916

Shpotyuk O, Calvez L, Petracovschi E, Klym H, Ingram A, Demchenko P (2014) Thermally-induced crystallization behaviour of 80GeSe2-20Ga2Se3 glass as probed by combined X-ray diffraction and PAL spectroscopy. J Alloys Compd 582:323–327

Hubert M, Delaizir G, Monnier J, Godart C, Ma H, Zhang X, Calvez L (2011) An innovative approach to develop highly performant chalcogenide glasses and glass-ceramics transparent in the infrared range. Opt Express 19(23):23513–23522

Cui S, Chahal R, Shpotyuk Ya, Boussard-Pledel C, Lucas J, Charpentier F, Tariel H, Loreal O, Nazabal V, Sire O, Monbet V, Yang Z, Lucas P, Bureau B (2014) Selenide and telluride glasses for mid-infrared bio-sensing. Proc SPIE 8938:893805-1-9.

Eggleton BJ, Luther-Davies B, Richardson K (2011) Chalcogenide photonics. Nat Photonics 5:141–148

Rodriguez-Carvajal J (2001) Recent developments of the program FullProf. Commission on Powder Diffraction Newsletters 26:12–19

Kansy J (1996) Microcomputer program for analysis of positron annihilation lifetime spectra. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res, Sect A 374(2):235–244

Krause-Rehberg R, Leipner H (1999) Positron annihilation in semiconductors: defect studies. Springer, Heidelberg

Shpotyuk O, Filipecki J (2003) Free volume in vitreous chalcogenide semiconductors: possibilities of positron annihilation lifetime study. WSP, Czestochowa

Keeble DJ, Brossmann U, Puff W, Würschum R (2012) Positron annihilation studies of materials. In: Kaufmann EN (ed) Characterization of materials. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, pp 1899–1925

Tuomisto F, Makkonen I (2013) Defect identification in semiconductors with positron annihilation: experiment and theory. Rev Mod Phys 85:1583–1631

Seeger A (1974) The study of defects in crystals by positron annihilation. Appl Phys 4(3):183–199

Khan MY, Ali SZ (1980) Optical and scanning electron microscopic examination of α- and β-Ga2Se3. J Cryst Growth 49(2):303–308

Ali SZ, Khan MY (1981) Duplex character of defect zinc blende structure of α- and γ-Ga2Se3. Acta Cryst 37:C104b

Massalski TB, Okamoto H, Subramanian PR, Kacprzak L (1990) Binary alloy phase diagrams, 2nd edn. ASM International, Materials Park, OH

Hyla M, Filipecki J, Shpotyuk O, Popescu M, Balitska V (2007) Stoichiometric arsenic sulphoselenides as testing probes for positron trapping in chalcogenide glasses. J Optoelectron Adv Mat 9:3177–3181

Ingram A, Golovchak R, Kostrzewa M, Wacke S, Shpotyuk M, Shpotyuk O (2012) Compositional dependences of average positron lifetime in binary As-S/Se glasses. Physica B 407(4):652–655

Shpotyuk O, Golovchak R, Ingram A, Boyko V, Shpotyuk L (2013) Comparative study of extended free-volume defects in As- and Ge-based glassy semiconductors: theoretical prediction and experimental probing with PAL technique. Phys Status Solidi C 10(1):117–120

Jensen KO, Salmon PS, Penfold IT, Coleman PG (1994) Microvoids in chalcogenide glasses studied by positron annihilation. J Non-Cryst Solids 170(1):57–64

Feltz A (1993) Amorphous inorganic materials and glasses. VCH Publishers, New York

Kastner M (1973) Compositional trends in the optical properties of amorphous lone-pair semiconductors. Phys Rev B 7(12):5237–5252

Pauling L (1960) The nature of the chemical bond. Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca

Shpotyuk OI, Filipecki J, Balitska VO (2008) Radiation-induced extended free-volume defects in mixed ternary Ge-As/Sb-S glasses studied with PALS technique. J Optoelectron Adv Mat 10:3193–3197

Shpotyuk O, Ingram A, Demchenko P (2015) Free volume structure of realgar α-As4S4 by positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy. J Phys Chem Solids 79:49–54

Shpotyuk O, Hyla M, Boyko V (2015) Compositionally-dependent structural variations in glassy chalcogenides: the case of binary As-Se system. Comput Meter Sci 110:144–151

Exciting Beryllium, program package. 2013. http://exciting-code.org. Accessed 25 Sept 2015.

Alekseeva OK, Mikhailov VI, Shantarovich VP (1978) Positron annihilation in point defects of the glassy As-Se system. Phys Status Solidi A 48:K169–K173

Tichy L, Ticha H (1995) Covalent bond approach to the glass-transition temperature of chalcogenide glass. J Non-Cryst Solids 189:141–146

Aitken BG, Ponader CW, Quimby RS (2002) Clustering of rare earths in GeAs sulfide glass. C R Chimie 5(12):865–872

Churbanov MF, Scripachev IV, Shiryaev VS, Plotnichenko VG, Smetanin SV, Kryukova EB, Pyrkov YN, Galagan BI (2013) Chalcogenide glasses doped with Tb, Dy and Pr ions. J Non-Cryst Solids 326–327:301–305

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by POLONIUM common actions program for years 2015–2016 realized in respect to bilateral agreement on scientific-technical cooperation between Polish and French governments from 1966. Support from Marie-Curie Action FP7-PEOPLE-2010-ITN under the GlaCERCo project is also acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors (YaSh, AI, OSh, AD, CB, BB) developed the methodological algorithms to treat experimental PAL spectra. AI and YaSh performed the experiments to characterize the samples. YaSh, CB, and BB prepared the tested objects. AD and ShYa performed the SEM and EDS analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shpotyuk, Y., Ingram, A., Shpotyuk, O. et al. Free-Volume Nanostructurization in Ga-Modified As2Se3 Glass. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 20 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1237-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1237-8