Abstract

The cubic Fe3O4 nanoparticles with sharp horns that display the size distribution between 100 and 200 nm are utilized to substitute the magnetic sensitive medium (carbonyl iron powders, CIPs) and abrasives (CeO2/diamond) simultaneously which are widely employed in conventional magnetorheological finishing fluid. The removal rate of this novel fluid is extremely low compared with the value of conventional one even though the spot of the former is much bigger. This surprising phenomenon is generated due to the small size and low saturation magnetization (M s) of Fe3O4 and corresponding weak shear stress under external magnetic field according to material removal rate model of magnetorheological finishing (MRF). Different from conventional D-shaped finishing spot, the low M s also results in a shuttle-like spot because the magnetic controllability is weak and particles in the fringe of spot are loose. The surface texture as well as figure accuracy and PSD1 (power spectrum density) of potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) is greatly improved after MRF, which clearly prove the feasibility of substituting CIP and abrasive with Fe3O4 in our novel MRF design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) is the unique nonlinear single crystal that is large enough as optical frequency conversion and electro-optical switch in high-fluence environment such as inertial confinement fusion (ICF) laser system. However, this crystal presents a great challenge to the ultra-precision manufacturing due to its low hardness, temperature sensitivity, and water solubility [1–3]. Today, the common precise process for KDP is single-point diamond turning (SPDT) [4–6]. Though highly successful of this technique, it would introduce turning grooves and subsurface defects via pure mechanical force which may lower the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) in strong laser application. Furthermore, the waviness errors that induced by vibration, straightness, and some other ambient factors are extremely difficult to be eliminated at present [7, 8]. With increased demands on surface quality of KDP ultra-precision manufacturing, more and more novel processing routes are employed to meet the elevated requirements.

Magnetorheological finishing (MRF) is an advanced sub-aperture polishing technology that contains magnetic sensitive carbonyl iron powders (CIPs) and nonmagnetic abrasive incorporated in aqueous medium. The choice of abrasive is directed by the interaction with workpiece such as the physical properties (e.g., hardness) and chemical properties (e.g., chemical durability). It is considered to be an excellent, deterministic process for finishing optics to high precision with few subsurface defects [9–11]. For a typical MRF process, the fluid is pumped and ejected through a nozzle onto a strong magnetic rotating wheel, and the ribbon is stiffened upon passing into the vicinity of workpiece. The removal rate is determined by process parameters as well as material properties of fluid and workpiece [12–14]. The finishing spot in the contacting zone between ribbon and workpiece is characterized to generate removal function arithmetic.

Arrasmith et al. has reported that nonaqueous magnetorheological fluid which was composed of CIPs, nanodiamonds, and dicarboxylic ester could successfully polish a previously diamond-turned KDP to remove all turning grooves without deteriorating the roughness [15]. Menapace et al. and Peng et al. have reported the MRF of KDP via water deliquescence without abrasive which also could achieve the smooth surface [1, 16]. However, the surface quality still does not meet the requirement in engineering and many researches need to be done to obtain better manufacturing level. Firstly, there are at least two kinds of particles (CIPs and abrasives) in the fluid, increasing the difficulty of fluid design and preparation. Secondly, CIPs’ size distribution is 0.5–3 μm and much larger than the value of nanosized abrasives. Due to CIPs inevitably taking part in the material removal during MRF, the existence of huge particles would introduce obviously scratches and block the improvement of finishing quality [17]. Thirdly, Kozhinova et al. showed that soft CIP and silica abrasive with low removal rate might produce better surface roughness in soft ZnS MRF [18]. These motivate us to meliorate the conventional MRF technology via designing a novel finishing fluid with sole, small, and weak magnetic particles and adjustable low removal rate to improve the surface quality of soft KDP finishing.

Fe3O4 is a common magnetic functional material that has been widely researched in recent years for its outstanding properties and potential applications in various fields, such as ferrofluids, catalysts, colored pigments, microwave absorber, high-density magnetic recording media, and medical diagnostics [19–22]. In addition, the particle’s size can be accurately controlled from nanometer to micrometer with narrow size distribution; it can also be dispersed easily with a surfactant by surface modification due to its chemical activation which is alive [23–25]. In this paper, we put forward an assumption to utilize the Fe3O4 nanoparticles to substitute conventional CIP and abrasive simultaneously, which means Fe3O4 plays the role of a magnetic sensitive particle as well as an abrasive. The idea is based on the understanding that small, narrow size distribution, low hardness, and weak magnetic particle with low removal rate are beneficial for the finishing of the ultra-precise surface.

Methods

The CIPs were purchased from BASF Co., Ltd. (Germany), and Fe3O4 nanoparticles were obtained from Aipurui Reagent Co. Ltd. (Nanjing, China) without any further surface modification. Other chemical reagents were purchased from Aladdin Chemical Co., Ltd. without purification. The typical magnetorheological fluid consists of basic liquid, functional particles (CIPs and abrasives, or Fe3O4), and some additives. The dispersion of particles to avoid scratch during finishing was achieved via high-shear emulsification and ultrasonic fragmentation.

The microstructure and morphology were characterization by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Ultra 55) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Zeiss Libra 200FE). The magnetic studies were carried out on a Lake Shore 7410 vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). The finishing spot was taken on a KDP with the ribbon immersion depth of 0.5 mm. The 3D surface morphology of the finished surface was characterized by Taylor Hobson CCI lite with 20× objective of full resolution. After finishing the experiment on a 100 mm × 100 mm KDP via self-developed MRF apparatus and cleaning, the surface figure accuracy was examined and analyzed by Zygo interferometer.

Results and Discussion

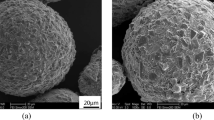

Spherical CIP particles with sizes between 0.5–3 μm are shown in Fig. 1; the size distribution is extremely extensive and there are too many large particles. Figure 2 displays the morphology of Fe3O4 nanoparticles, from which we can see that the size distribution is 100–200 nm with cubic shape, and the edge is clear and four horns of every particle are sharp. Though the particles apparently agglomerate together due to intrinsic static magnetic absorption force, it should be noted that these incompact agglomerations may not greatly influence the subsequently finishing quality because the slurry is stirred online in the delivery system and the soft agglomerations would be dispersed.

The magnetization hysteresis loops of Fe3O4 particles and CIPs are shown in Fig. 3. It can be inferred from the hysteresis loop that Fe3O4 particles are typical soft magnetic materials. We can see that the M s of Fe3O4 is 84.06 emu/g and the value of CIPs is 194.61 emu/g. It is reported that the existence of non-collinear spin structure which originated from the pinning of surface spins would result in the reduction of magnetic moment. The low M s means Fe3O4 will be promptly saturated under an external magnetic field and the corresponding shear force induced by the field would not be as large as that of CIP which has higher M s.

Based on the above analysis, we deduce that the small particle size and low shear stress may be beneficial to improve the surface quality in soft KDP finishing. Different from conventional magnetorheological finishing fluid that contains CIP and abrasive to generate a smooth surface, we design a novel finishing fluid by choosing the Fe3O4 nanoparticles to substitute both the CIP and abrasive as shown in Fig. 4.

The morphology and profile of finishing spot are exhibited in Fig. 5; the length is as large as 34 mm and the width is as large as 12.5 mm. The size is obviously bigger than conventional spots that are obtained on hard glasses with commercial aqueous CeO2/diamond finishing fluid containing CIPs [11]. However, the peak removal rate is only 0.097 λ/min and the volume removal rate is only 0.013 mm3/min, which are evidently lower than the value of commercial fluid between 4 and 30 λ/min [14]. This strange phenomenon can be easily understood by comparing the size and magnetic parameter of Fe3O4 and CIP.

Kordonski et al. have proposed the particle force model via taking the form of

where K is the dimensionless coefficient, ρ p is the density, d p is the diameter, and γ is the shear rate [14]. Generally, the density of Fe3O4 (5.18 g/cm3) is obviously lower than that of CIP (7.845 g/cm3). Secondly, the diameter of nanosized Fe3O4 (100 nm) is much smaller than the microsized CIP (1 μm). So, according to Equation (1), the particle force of Fe3O4/CIP is 6.6 × 10−5 when at the same shear rate, indicating that the shear stress will be extremely weak compared with the value of CIP.

Furthermore, Miao et al. have calculated the shear stress by considering the magnetic field effectiveness via MRF experiments for a series of materials containing optical glasses and found a positive dependence of peak removal rate with shear stress [26]. The effect of both shear stress and mechanical properties are incorporated into a predictive equation for material removal as shown in

where MRR is the material removal rate, \( {C}_{P,\mathrm{M}\mathrm{R}\mathrm{F}\left(\tau,\ \mathrm{F}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{M}\right)}^{\mathit{\hbox{'}}} \) is a modification of Preston’s coefficient in terms of shear stress, τ. And \( \frac{E}{K_c{H}_V^2} \) is the figure of material merit (FOM), where E denotes to Young’s modulus (resistance to elastic deformation), H V is related to Vickers hardness (resistance to plastic deformation), and K c is fracture toughness (resistance to fracture/crack growth). The M s of Fe3O4 is much lower than that of CIP as shown in Fig. 3, hinting that the induced magnetic flux is not large enough and the corresponding shear stress that is controlled by the magnetic field is weak. The weak shear stress would inevitably result in low removal rate according to Equation (2). However, it does not mean that the lower the removal rate, the better the finishing fluid. Both smoothness and manufacturing efficiency should be considered to achieve a balance. That is why we select the cubic Fe3O4 nanoparticles rather than the smaller or spherical ones for the sake of utilizing spiculate friction of horns to maintain relative mechanical removal ability. Otherwise, too low removal rate would result in unacceptable finishing period. It should be noted that the shuttle-like spot is evidently different from conventional spot with D-shaped framework [11, 14]. This difference may be also arising from the small M s of Fe3O4. The controllability of Fe3O4 under an external magnetic field is weak compared with CIP, especially in the area that is far from the center of the spot. So, the Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the fringe of the spot are loose and the spot is enlarged.

Through the above discussion, it is easy to understand why the removal rate of the fluid containing Fe3O4 nanoparticles with much bigger and deeper spot is inversely lower than the value of conventional finishing fluid containing CIPs and CeO2/diamond abrasives. In order to validate our assumption that low removal rate may be in favor of the improvement of surface quality, we explore the surface texture of the finished KDP as shown in Fig. 6. Figure 6a, b clearly exhibits a great deal of “falling star” like pits and scratches; we may deduce these flaws are arising from the strike of CIP because the widths are micrometer-sized and just located in the CIP range. However, the surface texture is obviously improved if Fe3O4 is introduced as shown in Fig. 6c, d, few pits and scratches can be found, and there are only fine grooves which may be produced by the rolling and shaving actions between nanoparticles and KDP during finishing.

With the spot and removal function as discussed above, we take an experiment on a 100 mm × 100 mm KDP to display the finishing effectiveness of Fe3O4 nanoparticles instead of conventional CIPs and abrasives. The initial low-frequency figure accuracy PV is 0.646 λ (1 λ = 632 nm) as shown in Fig. 7a, and it is converged to 0.178 λ after MRF (Fig. 7c). In addition, the RMS of middle-frequency PSD1 is reduced from 23.083 to 6.539 nm as shown in Fig. 7b, d after MRF. All the data are characterized; waiting for 48 h after processing for the sake of releasing residual stress due to KDP is extremely sensitive to temperature variation and applied force. These inspiring results clearly prove the feasibility of utilizing Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a magnetic sensitive medium and an abrasive simultaneously. Continuous exploration to further improve surface quality on large-aperture KDP is under work.

Conclusions

The size distribution of cubic Fe3O4 nanoparticles with sharp edges and horns is determined by TEM within 100–200 nm. A novel magnetorheological finishing fluid is designed by substituting conventional CIP and abrasive simultaneously with Fe3O4. The removal rate is extremely low compared with the value of conventional fluid though the finishing spot is much bigger, and the shuttle-like spot is different from the conventional D-shaped configuration. These strange phenomena are arising from the small size and inherently weak M s of Fe3O4 by theoretical analysis. The finishing experiment exhibits nice surface texture and obvious convergence of figure accuracy PV and PSD1, validating the feasibility of our novel Fe3O4 design in MRF.

References

Menapace JA, Ehrmann PR, Bickel RC (2009) Magnetorheological finishing (MRF) of potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) crystals: nonaqueous fluids development, optical finish, and laser damage performance at 1064 nm and 532 nm. Proc SPIE 7504:750414

Shafrir SN, Romanofsky HJ, Skarlinski M, Wang MM, Miao CL, Salzman S et al (2009) Zirconia-coated carbonyl-iron-particle-based magnetorheological fluid for polishing optical glasses and ceramics. Appl Optics 48:6797–6810

Ji F, Xu M, Wang BR, Wang C, Li XY, Zhang YF et al (2015) Preparation of methoxyl poly(ethylene glycol) (MPEG)-coated carbonyl iron particles (CIPs) and their application in potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) magnetorheological finishing (MRF). Appl Surf Sci 353:723–727

Chen MJ, Li MQ, Cheng J, Jiang W, Wang J, Xu Q (2011) Study on characteristic parameters influencing laser-induced damage threshold of KH2PO4 crystal surface machined by single point diamond turning. Appl Phys 110:113103

Cheng J, Chen MJ, Liao W, Wang HJ, Xiao Y, Li MQ (2013) Fabrication of spherical mitigation pit on KH2PO4 crystal by micro-milling and modeling of its induced light intensification. Opt Express 21:16799–16813

Chen MJ, Cheng J, Yuan XD, Liao W, Wang HJ, Wang JH et al (2015) Role of tool marks inside spherical mitigation pit fabricated by micro-milling on repairing quality of damaged KH2PO4 crystal. Sci Rep 5:14422

Chen SS, Li SY, Peng XQ, Hu H, Tie GP (2015) Research of polishing process to control the iron contamination on the magnetorheological finished KDP crystal surface. Appl Optics 54:1478–1484

Chen MJ, Li MQ, Cheng J, Xiao Y, Pang QL (2013) Study on the optical performance and characterization method of texture on KH2PO4 surface processed by single point diamond turning. Appl Surf Sci 279:233–244

Jacobs SD (2007) Manipulating mechanics and chemistry in precision optics finishing. Sci Technol Adv Mat 8:153–157

Miao C, Shen R, Wang M, Shafrir SN, Yang H, Jacobs SD (2011) Rheology of aqueous magnetorheological fluid using dual oxide-coated carbonyl iron particles. J Am Ceram Soc 94:2386–2392

Beier M, Scheiding S, Gebhardt A, Loose R, Risse S, Eberhardt R et al (2013) Fabrication of high precision metallic freeform mirrors with magnetorheological finishing (MRF). Proc SPIE 8884:88840S

Wang C, Li XY, Ji F, Wei QL, Zhang YF, Gao W et al (2015) The particle behavior analysis and design in the improvement of KDP finishing. Proc SPIE 9532:95321Z

Sidpara A, Jain VK (2012) Theoretical analysis of forces in magnetorheological fluid based finishing process. Int J Mech Sci 56:50–59

Kordonski W, Gorodkin S (2011) Material removal in magnetorheological finishing of optics. Appl Optics 50:1984–1994

Jacobs SD, Arrasmith SR (1999) Development of new magnetorheological fluids for polishing CaF2 and KDP. LLE Rev 80:213–219

Peng XQ, Jiao FF, Chen HF, Tie GP, Shi F, Hu H (2011) Novel magnetorheological figuring of KDP crystal. Chin Opt Lett 9:102201

Shorey AB, Jacobs SD, Kordonski WI, Gans RF (2001) Experiments and observations regarding the mechanisms of glass removal in magnetorheological finishing. Appl Optics 40:20–33

Kozhinova IA, Romanofsky HJ, Maltsev A, Jacobs SD, Kordonski WI, Gorodkin SR (2005) Minimizing artifact formation in magnetorheological finishing of CVD ZnS flats. Appl Optics 44:4671–4677

Cao YH, Li C, Li JL, Li QY, Yang JJ (2015) Magnetically separable Fe3O4/AgBr hybrid materials: highly efficient photocatalytic activity and good stability. Nanoscale Res Lett 10:251

Iacovita C, Stiufiuc R, Radu T, Florea A, Stiufiuc G, Dutu A et al (2015) Polyethylene glycol-mediated synthesis of cubic iron oxide nanoparticles with high heating power. Nanoscale Res Lett 10:391

Chao YC, Huang WH, Cheng KM, Kuo CS (2014) Assembly and manipulation of Fe3O4/coumarin bifunctionalized submicrometer janus particles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 6:4338–4345

Urbas K, Aleksandrzak M, Jedrzejczak M, Jedrzejczak M, Rakoczy R, Chen XC, Mijowska E (2014) Chemical and magnetic functionalization of graphene oxide as a route to enhance its biocompatibility. Nanoscale Res Lett 9:656

Jia XL, Li WS, Xu XJ, Li WB, Cai Q, Yang XP (2015) Numerical characterization of magnetically aligned multiwalled carbon nanotube–Fe3O4 nanoparticle complex. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 7:3170–3179

Jian X, Cao Y, Chen GZ, Wang C, Tang H, Yin LJ et al (2014) High-purity Cu nanocrystal synthesis by a dynamic decomposition method. Nanoscale Res Lett 9:689

Rumpf K, Granitzer P, Koshida N, Poelt P, Reissner M (2014) Magnetic interactions between metal nanostructures within porous silicon. Nanoscale Res Lett 9:412

Miao CL, Shafrir SN, Lambropoulos JC, Mici J, Jacobs SD (2009) Shear stress in magnetorheological finishing for glasses. Appl Optics 48:2585–2594

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51202228, 51575501), the CAEP Foundation (Grant No.:2015B0203030), and the Foundation Research Program of Defense (No. A1520133005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

FJ formulated the idea of the investigation and drafted the manuscript, and MX is his supervisor. CW participated in the design of the study and coordination of the work. XYL mainly contributed on the fabrication of the Fe3O4 fluid and WG measured the magnetic properties. YFZ has taken part in the finishing experiment. BRW, GPT, and XBY participated in the analysis of the result and mechanism. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, F., Xu, M., Wang, C. et al. The Magnetorheological Finishing (MRF) of Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate (KDP) Crystal with Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 79 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1301-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1301-4