Abstract

A series of TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2 nanocomposites were synthesized using a liquid-phase method and characterized by various techniques, namely, nitrogen adsorption–desorption, X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Raman spectroscopy, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy, and photon correlation spectroscopy (PCS). It was revealed that the component ratio and calcination temperature affect the phase composition of nanocomposites. Composites TiZrSi1 (TiO2:ZrO2:SiO2 = 3:10:87) and TiZrSi2 (10:10:80) calcined at 1100 °С demonstrate the presence of t-ZrO2 crystallites in TiZrSi1 and ZrTiO4 phase in TiZrSi2. The samples calcined at 550 °С were amorphous as it was found from XRD data. According to the Raman spectra, the bands specific for anatase are observed in TiZrSi2. According to XPS data, Zr and Ti are in the highest oxidation state (+4). Textural analysis shows that initial silica is mainly meso/macroporous, but composites are mainly macroporous. The particle size distributions in aqueous media showed a tendency of increasing particle size with increasing TiO2 content in the composites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

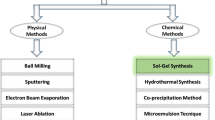

Highly disperse (nanoparticulate) oxide composites are of great interest for individual applications not only as heterogeneous catalysts with an adjustable set and strength of surface active sites [1–4] but also as a part of organic–inorganic composites and polymer fillers [5, 6]. Combination of dissimilar oxides allows to create surface active sites, which are absent in individual components [7]. The nature of active sites of solid acid catalysts is defined by mobile surface protons generating Brønsted acid sites and coordinately unsaturated cationic centers as Lewis acid sites [8]. Therefore, much attention has been focused on development of binary or ternary metal oxides as heterogeneous catalysts [1]. Thus, the main objective to prepare such nanoscale systems is aimed at controlling their surface composition and particle morphology. One of the common methods of the synthesis of nanoparticulate oxides is based on the use of a substrate of a high specific surface area. The fumed silica properties are a convenient vehicle for the synthesis of the mentioned composites due to silica inertness in catalytic processes, developed surface area, and homogeneity of active sites on a surface [9]. Among various metal oxide catalysts, the combination of titania and zirconia has attracted attention in recent years. These mixed oxides have been extensively used as catalysts and catalyst supports for a wide variety of reactions [2]. TiO2–ZrO2 mixed oxide composites are used as photocatalysts due to a reduced bandgap in comparison to individual components [3, 10–15]. They have been reported to exhibit a high surface acidity due to an imbalance of charges resulting from the formation of the Ti–O–Zr bridges [14, 16]. According to [11], TiO2/SiO2 and TiO2/ZrO2 are characterized by more acidic properties than single/pure components. TiO2–ZrO2 system is a strong solid acid showing catalytic activity in such reactions as isomerization and cracking of alkanes, hydration and polymerization of alkenes, etc. [7, 17]. The most widely employed methods to prepare TiO2–ZrO2 composites are co-precipitation [18, 19] and sol–gel synthesis [2, 10, 20, 21]. A method of grafting of mixed oxides onto a surface of highly disperse matrices with nonporous nanoparticles can be a good alternative to the mentioned methods. Therefore, the objective of this study was the synthesis of silica-supported titania–zirconia nanocomposites (TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2) and investigation of their morphological and structural properties.

Methods

Materials

Fumed silica (pilot plant of the Chuiko Institute of Surface Chemistry, Kalush, Ukraine), zirconium (Aldrich, > 98 % Zr(acac)4), and titanyl (C10H11O5Ti) acetylacetonates (Merck) were used as precursors to prepare oxide composites.

Synthesis of Silica-Supported Titania–Zirconia Nanocomposites

Silica-supported titania–zirconia nanocomposites (TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2) were prepared using a liquid-phase method. The synthesis was performed in a glass double-neck reactor equipped with a propeller agitator and a reflux condenser. Zr(acac)4 and C10H11O5Ti solutions in isopropyl alcohol (IPA) were added to fumed silica (5 g; previously calcined at 500 °C; specific surface area S = 283 m2/g) at 82.5 °С. The reaction mixture was stirred in the refluxing tube for 1 h. Then, IPA and acetylacetone were removed from the mixture by evacuation. The solid products were dried and calcined at 550 °С and 1100 °С for 1 h. According to [22], the temperature range 500–550 °C corresponds to the destruction of acetylacetonate ligands and complete removal of the volatile carbon components upon oxide formation. But at 550 °C, a high probability of the formation of the amorphous structure takes place, while the temperature of 1100 °C was chosen as sufficient for crystalline structure formation. The content of grafted TiO2 was varied from 3 to 10 wt.% while ZrO2 content was held constant at 10 wt.% (samples TiZrSi1 and TiZrSi2, respectively).

X-Ray Powder Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

X-ray diffraction patterns were recorded at room temperature using a DRON-3M diffractometer (Burevestnik, St. Petersburg, Russia) with Cu K α (λ = 0.15418 nm) radiation and a Ni filter in the 2θ range from 10° to 70°. The average size of nanocrystallites (D cr) was estimated according to the Scherrer equation [23]. Crystalline structure of samples was analyzed using the JCPDS Database (International Center for Diffraction Data, PA, 2001) [24]. Silica was totally amorphous in all samples.

Raman Spectroscopy (RS)

The Raman spectra were recorded over the 150–3200-cm−1 range using an inVia Reflex Microscope DMLM Leica Research Grade, Reflex (Renishaw, UK), with Ar+ ion laser excitation at λ 0 = 514.5 nm. For each sample, the spectra were recorded at several points in order to ascertain the homogeneity of the sample, and the averages of all these spectra were plotted.

X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

The XPS measurements were performed using a VG Scienta R4000 electron analyzer with an MX650 monochromatized Al K α (1486.6 eV) radiation source. The binding energy (BE) was referenced to Si 2p (BE = 103.5 eV) with an accuracy of ±0.1 eV. Peak fitting was done using Casa XP5 with Shirley background and 10:90 Lorentzian/Gaussian convolution product shapes. The atomic concentration ratios were achieved by determining the elemental peak areas, following a Shirley background subtraction by the usual procedures documented in the literature [25].

High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM)

The particulate morphology was analyzed using high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) employing a Tecna™ G2 T20 X-TWIN (FEI Company, USA) apparatus operating at a voltage of 200 kV with LaB6 electron source. The samples were supported on holey carbon copper grids by dropping ethanol suspensions containing uniformly dispersed oxide powders.

Textural Characterization

To analyze the textural characteristics of TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2 nanocomposites, low-temperature (77.4 K) nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were recorded using an automatic gas adsorption analyzer ASAP 2405N (Micromeritics Instrument Corp., USA) after outgassing the samples at 110 °C for 2 h in a vacuum chamber. The values of the specific surface area (S BET) were calculated according to the standard BET method [26]. The total pore volume V p was evaluated by converting the volume of adsorbed nitrogen at p/p 0 = 0.98–0.99 (p and p 0 denote the equilibrium pressure and saturation pressures of nitrogen at 77.4 K, respectively) to the volume of liquid nitrogen per gram of adsorbent. The nitrogen desorption data were used to compute the pore size distributions (differential f V ~ dV p/dR and f S ~ dS/dR) using a self-consistent regularization (SCR) procedure under non-negativity condition (f V ≥ 0 at any pore radius R) at a fixed regularization parameter α = 0.01 with voids (V) between spherical nonporous nanoparticles packed in random aggregates (V/SCR model) [27]. The differential pore size distributions with respect to pore volume f V ~ dV/dR, ∫f VdR ~ V p were re-calculated to incremental pore size distributions (IPSD) at ΦV(R i ) = (f V(R i+1) + f V(R i ))(R i+1 − R i )/2 at ∑ΦV(R i ) = V p). The f V and f S functions were also used to calculate contributions of micropores (V micro and S micro at 0.35 nm < R < 1 nm), mesopores (V meso and S meso at 1 nm < R < 25 nm), and macropores (V macro and S macro at 25 nm < R < 100 nm).

Particle Size Distribution in Aqueous Media

Particle sizing for the aqueous suspensions of different fine oxides were carried out using a Zetasizer 3000 (Malvern Instruments) apparatus based on photon correlation spectroscopy (PCS, λ = 633 nm, Θ = 90°, software version 1.3).

The aqueous suspensions of oxides 0.1 wt.% were prepared using an ultrasonic disperser for 5 min (Sonicator Misonix Inc., power 500 W and frequency 22 kHz) prior to measuring particle size distribution.

Discussion

Textural Characterization

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms obtained for initial silica and composites (Fig. 1a) demonstrate sigmoidal-shaped behavior with a narrow hysteresis loop. The incremental pore (voids between particles in aggregates) size distribution functions (Fig. 1b) show that the textural characteristics change after the modification.

The specific surface area (Table 1, S BET) does not demonstrate a significant reduction after grafting of titania/zirconia. However, the total pore volume increases for TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2 compared to the initial silica. Furthermore, there is a significant decrease in mesopore contribution to the total porosity with a simultaneous increase in contribution of macropores. Moreover, the microporosity is slightly reduced for composites compared to the initial silica. Thus, the analysis of the results suggests the existence of mainly meso/macroporosity of aggregates of the initial silica and mainly macroporosity of the composites (Fig. 1b).

High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy

HRTEM images of TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2 nanocomposites (Fig. 2) show the formation of titania–zirconia particles (dark structures) at the silica surface (light structures). The aggregated structures of grafted oxides varying between 15 and 50 nm in size are well observed for TiZrSi1–2. Composites look like more compacted than initial silica. Therefore, contribution of macropores increases (Fig. 1b), as well as the total pore volume V p and V macro (Table 1) as an increased part of the empty volume (V em = 1/ρ b−1/ρ 0, where ρ 0 and ρ b are the true density of oxide nanoparticles and bulk density of the powder, respectively), in the powders. Note that any treatment or modification of fumed silica results in a decrease in the value of V em, i.e., the value of ρ b increases, and sometimes the value of V p increases, despite a decrease in V em, because nitrogen can fill only a portion of macropores even at p/p 0 → 1 [28].

X-Ray Powder Diffraction Analysis

XRD analysis of TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2 containing different amounts of TiO2 (Fig. 3) shows that the samples TiZrSi1 and TiZrSi2 calcined at 550 °С are amorphous. A broad peak in the range of 20–23° is due to amorphous silica [29, 30]. Calcination at 1100 °C resulted in the appearance of crystalline phases: t-ZrO2 (PDF-ICDD 80-0965) for TiZrSi1 and ZrTiO4 (PDF-ICDD 74-1504) for TiZrSi2 (Table 2). For TiZrSi1, there are four sharp peaks at 30.5°, 35.3°, 50.4°, and 60.2°, which can be attributed to diffraction planes (111), (200), (220), and (311) of tetragonal zirconia (No. 79–1771). TiZrSi2 is characterized by peaks at 25.3°, 30.5°, 35.3°, 42.1°, 50.4°, 53.8°, and 61.4°, which can be assigned to the planes (101), (111), (200), (211), (202), (204), and (311) of crystalline ZrTiO4. The broad diffraction peaks indicated a small size of crystallites that signifies the influence of the silica substrate preventing consolidation of nuclei of grafted oxides. The average size of crystallites (D cr) revealed a nominal increase with increasing titania content (Table 2). Thus, the use of fumed silica as the inert substrate results in the formation of small nanocrystallites of grafted oxides, only.

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 4) allows to get more information on the sample structure, composition effects, features of phase transition, and the quantum size effect. Fumed silica does not show any Raman features, as reported in the literature [31, 32]. It is known that zirconia exists as three polymorphs: monoclinic (m-ZrO2), tetragonal (t-ZrO2), and cubic (c-ZrO2). However, no Raman bands at 280, 316, 462, and 644 cm−1 due to tetragonal ZrO2 [33] or at 615 and 638 cm−1 due to monoclinic ZrO2 [34] are observed.

Additionally, no Raman bands at 148, 263, 476, and 550 cm−1 due to three-dimensional amorphous zirconia [35] are detected. For each sample, the spectra were recorded at several points, and no shift in the band position or differences of width were observed. This observation clearly reveals that all of the samples are mostly in a homogeneous state. For sample TiZrSi1, characteristic Raman bands are not observed. However, for sample TiZrSi2, the well-resolved Raman peaks at 143, 400, 500, 518, 630, 810, and 1083 cm−1 are observed. Some of these bands are specific to anatase [36] at 143 cm−1 (Eg, very strong), 197 cm−1 (Eg), 396 cm−1 (B1g), 514 cm−1 (A1g, B1g), and 637 cm−1 (Eg).

The obtained Raman spectrum is well correlated with the data for ZrTiO4 [37, 38]. It was noted [33] that the variations in broad bands at 148 (Eg), 401 (B1g), 522 (A1g or B1g), and 648 (Eg) cm–1 are characteristic for anatase depending on the ratio TiO2:ZrO2 in films, but no other bands characteristic for other polymorphs were found. According to [37], the degree of line broadening in a peak at 815 cm−1 as probing local microstructure was chosen because this peak did not overlap with other peaks and exhibited a pronounced change in the degree of line broadening.

Thus, it can be seen that anatase is formed only at relatively high concentration of TiO2 in the composite, whereas at a low concentration of TiO2, the amorphous titania is observed. Based on the presence of the background at the location of line Eg(1) for TiZrSi2, an amorphous phase is also present. The intensity of the Raman bands depends on several factors including grain size and morphology [38]. A strong increase in line Eg(1) background at the presence of small (2–3 nm) crystallites was also noted previously [39]. Peak Eg(2) near 197 cm−1 has a very low intensity and in our composites is not observed.

The absence of any other Raman features providing inference that silica does not form any compound with titania and zirconia is in line with XRD observations.

Surface Characterization by XPS

Formation of chemical bonds between components in ternary oxides was investigated using the XPS method (Fig. 5). Two main peaks for silicon (Si 2s and Si 2p), two peaks for zirconium (Zr 3p and Zr 3d), and only one main peak for titanium (Ti 2p doublet) were detected in the spectra (Fig. 5). For all the samples, analysis of the 1s line of the carbon showed that the states with a binding energy within 284.7–290.8 eV are formed by a variety of carbon bonds of surface hydrocarbon contamination of samples [40].

For the analysis of the chemical state of elements forming nanolayers TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2, the following line core levels Si 2p, O 1s, Zr 3d, and Ti 2p were selected. The detailed XPS spectra of oxygen for silica and ternary oxide samples are compared (Fig. 6a). In oxygen O 1s region, one can see that the positions of O 1s are slightly shifted in samples TiZrSi1 and TiZrSi1 compared to the initial silica. For TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2, the O 1s peak can be divided into two bands O 1s A and O 1s B, and the ratio of these components depends on the content of titania (Fig. 6 and Table 3). The appearance of the O 1s peak at lower energy is due to the effects of TiO2 and ZrO2 with a large displacement of the electron density to the O atoms than that in silica.

The binding energy of the Si 2p peak ranged between 103.5 and 103.7 eV (Fig. 6b) that are consistent with the values reported in the literature [40]. The weak intensity of the spectra with large peak widths in case of TiZrSi1 and TiZrSi1 samples indicates that silica is not easily accessible at the surface due to the presence of titania–zirconia layers.

The Zr 3d5/2 and Ti 2p3/2 peaks (Fig. 6c, d) correspond to the binding energy of 183.1–183.3 and 459.3–459.6 eV, respectively, which represent the fully oxidized zirconium ion Zr4+ and titanium ion Ti4+ [39]. Such binding energies can be attributed both to the individual metal oxides [39] and to ZrTiO4 [41, 42]. The observed positive shifts of the peaks Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 (Fig. 6d) relatively to the peaks in individual titania (458.7 and 464.7 eV) [40] may testify the formation of the Ti–O–Zr bonds. The displacement was observed [43] for the mixed triple films TiO2/ZrO2/SiO2. Note that during mixed oxide formation, the inhibitive influence on the growth and agglomeration of the individual phases of the components occurs due to the formation of the Ti–O–Zr bonds. In the investigated samples, the shift of the Ti 2p3/2 peak relatively to pure TiO2 is larger for TiZrSi1 at smaller content of TiO2 than for TiZrSi2 with a high content of TiO2. This fact shows that at increasing TiO2 content in the ternary oxide, the number of the Ti–O–Zr bonds decreases, i.e., at higher content, TiO2 forms a separate phase, while at lower content it forms TiO2–ZrO2 mixed oxide.

Particle Size Distribution

The degree of aggregation/agglomeration of nanoparticles depends on their characteristics and interactions with the dispersion medium. The initial silica is characterized by nearly monomodal particle size distribution (PSD) with a maximum at 21 nm (Fig. 7a, curve 1).

However, the PSD for composites is bimodal with two peaks with respect to the particle number (Fig. 7a) and particle volume (Fig. 7b). The PSDs for TiZrSi1 and initial silica are similar, while for TiZrSi2, the aggregates are characterized by larger sizes ~500 nm. Note that there is a tendency of increasing particle size with increasing TiO2 content in the composites (Fig. 7, curves 2–3). The increase of the average particle size in aqueous suspensions can be associated as with a change in particle size during the formation of a new phase of ZrO2/TiO2 during the synthesis and also with influence of changes in surface structure and related electrokinetic properties of the oxide composites on the aggregation processes in an aqueous medium.

Conclusion

In the present study, highly disperse silica-supported titania–zirconia nanocomposites were synthesized by a liquid-phase method. The samples were examined using a set of techniques after their calcination at 550 and 1100 °C. The structural characteristics (phase composition, average size of crystallites) of the materials affected by pre-heating were determined from the XRD data. The XRD measurements indicated the presence of ZrTiO4 and anatase in TiZrSi2 and tetragonal zirconia in TiZrSi1 calcined at 1100 °C. The TiZrSi1 and TiZrSi2 samples calcined at 550 °С were XRD amorphous. The crystallinity slightly increased with increasing titania content in nanocomposites. There is no indication of compound formed with silica and titania or zirconia. The analysis of the nitrogen adsorption–desorption data and HRTEM indicates that the grafting new oxide phases changes the textural characteristics of the powders. The incremental pore size distribution functions revealed the existence of mainly meso/macroporosity of aggregates of initial silica and mainly macroporosity of TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2 nanocomposites. The HRTEM images show the presence of well-dispersed Zr–Ti–oxide nanocrystallites ~15–50 nm in size on the amorphous silica matrix. In line with XRD results, Raman spectra show that silica did not form any compound with titania or zirconia. The XPS results reveal that O 1s, Si 2p, Zr 3d, and Ti 2p core-level photoelectron peaks are sensitive to the phase composition of TiO2–ZrO2/SiO2 nanocomposites. Moreover, XPS measurements show that Zr and Ti ions are present in their highest oxidation states (+4). The shift of the peaks indicates the possible formation of titanium–zirconium mixed oxide. A tendency of increasing particle size with increasing TiO2 content in the composites was detected accordingly to the PSD characterization in the aqueous media.

References

Tanaka H, Boulinguiez M, Vrinat M (1996) Hydrodesulfurization of thiophene, dibenzothiophene and gas oil on various Co-Mo/TiO2-Al2O3 catalysts. Catal Today 29:209–213

Manrı́quez ME, López T, Gómez R, Navarrete J (2004) Preparation of TiO2–ZrO2 mixed oxides with controlled acid–basic properties. J Mol Catal A-Chem 220(2):229–237

Reddy BM, Khan A (2005) Recent advances on TiO2‐ZrO2 mixed oxides as catalysts and catalyst supports. Catalysis Rev 47:257–296

Vishwanathan V, Roh HS, Kim JW, Jun KW (2004) Surface properties and catalytic activity of TiO2–ZrO2 mixed oxides in dehydration of methanol to dimethyl ether. Catal Lett 96:23–28

Lü C, Yang B (2009) High refractive index organic–inorganic nanocomposites: design, synthesis and application. J Mater Chem 19:2884–2901

Hanemann T, Szabó DV (2010) Polymer-nanoparticle composites: from synthesis to modern applications. Materials 3:3468–3517

Tanabe K, Misono M, Ono Y, Hattori H (1989) New solids and bases. Kodansha–Elsevier, Tokyo

Corma A (1995) Inorganic solid acids and their use in acid-catalyzed hydrocarbon reactions. Chem Rev 95(3):559–614. doi:10.1021/cr00035a006

Iler RK (1979) The chemistry of silica: solubility, polymerization, colloid and surface properties and biochemistry of silica. Wiley, New York

Tomar LJ, Chakrabarty BS (2013) Synthesis, structural and optical properties of TiO2-ZrO2 nanocomposite by hydrothermal method. Adv Mat Lett 4(1):64–67

Fu X, Clark LA, Yang Q, Anderson MA (1996) Enhanced photocatalytic performance of titania-based binary metal oxides: TiO2/SiO2 and TiO2/ZrO2. Environ Sci Technol 30:647–653

Navio JA, Hidalgo MC, Roncel M, De la Rosa MA (1999) A laser flash photolysis study of the photochemical activity of a synthesised ZrTiO4. Comparison with parent oxides, TiO2 and ZrO2. Mater Lett 39(6):370–373

Kim JY, Kim CS, Chang HK, Kim TO (2010) Effects of ZrO2 addition on phase stability and photocatalytic activity of ZrO2/TiO2 nanoparticles. Adv Powder Technol 21(2):141–144

Wu B, Yuan R, Fu X (2009) Structural characterization and photocatalytic activity of hollow binary ZrO2/TiO2 oxide fibers. J Solid State Chem 182(3):560–565

Zhang M, Yu X, Lu D, Yang J (2013) Facile synthesis and enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of N and Zr co-doped TiO2 nanostructures from nanotubular titanic acid precursors. Nanoscale Res Lett 8:543

Reddy BM, Chowdhury B, Smirniotis PG (2001) An XPS study of the dispersion of MoO3 on TiO2–ZrO2, TiO2–SiO2, TiO2–Al2O3, SiO2–ZrO2, and SiO2–TiO2–ZrO2 mixed oxides. Appl Catal A 211:19–30

Yamaguchi T (1990) Recent progress in solid superacid. Appl Catal 61:1–25

Koohestania H, Alinezhad M, Sadrnezhaad SK (2015) Characterization of TiO2-ZrO2 nanocomposite prepared by co-precipitation method. In: Advances in Nanocomposite Research., http://docs.sadrnezhaad.com/papers/564.pdf, accessed 15 Feb 2015

Lin W, Lin L, Zhu YX, Xie YC, Scheurell K, Kemnitz E (2005) Novel Pd/TiO2–ZrO2 catalysts for methane total oxidation at low temperature and their 18O-isotope exchange behavior. J Mol Catal A-Chem 226(2):263–268

Perez-Hernandez R, Mendoza-Anaya D, Fernandez ME, Gomez-Cortes A (2008) Synthesis of mixed ZrO2–TiO2 oxides by sol–gel: microstructural characterization and infrared spectroscopy studies of NOx. J Mol Catal A-Chem 281:200–206

Lakshmi JL, Ihasz NJ, Miller JM (2001) Synthesis, characterization and ethanol partial oxidation studies of V2O5 catalysts supported on TiO2–SiO2 and TiO2–ZrO2 sol–gel mixed oxides. J Mol Catal A-Chem 165(1–2):199–209

Borysenko MV, Sulim IY, Borysenko LI (2008) Modification of highly dispersed silica with zirconium acetylacetonate. Theor Exp Chem. doi:10.1007/s11237-008-9030-0

Jenkins R, Snyder RL (1996) Introduction to X-ray powder diffractometry. Wiley, New York

JCPDS Database, International Center for Diffraction Data, 2001. http://www.icdd.com.

Briggs D, Seah MP (eds) (1990) Auger and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Practical surface analysis. Wiley, New York

Gregg SJ, Sing KSW (1982) Adsorption, surface area and porosity. Academic Press, London

Gun’ko VM (2014) Composite materials: textural characteristics. Appl Surf Sci 307:444–454

Gun’ko VM, Turov VV (2013) Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of interfacial phenomena. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Pengpeng L, Hailei Z, Jing W, Xin L, Tianhou Z, Qing X (2013) Facile preparation and electrochemical properties of amorphous SiO2/C composite as anode material for lithium ion batteries. J Power Sources 237:291–294

Mao Z, Wu Q, Wang M, Yang Y, Long J, Chen X (2014) Tunable synthesis of SiO2-encapsulated zero-valent iron nanoparticles for degradation of organic dyes. Nanoscale Res Lett 9:501

Reddy BM, Lakshmanan P, Khan A (2004) Investigation of surface structures of dispersed V2O5 on CeO2-SiO2, CeO2-TiO2, and CeO2-ZrO2 mixed oxides by XRD, Raman, and XPS techniques. J Phys Chem B 108:16855–16863

Reddy BM, Khan A (2005) Nanosized CeO2–SiO2, CeO2–TiO2, and CeO2–ZrO2 mixed oxides: influence of supporting oxide on thermal stability and oxygen storage properties of ceria. Catalysis Surv Asia 9:155–171

Gao X, Fierro JLG, Wachs IE (1999) Structural characteristics and catalytic properties of highly dispersed ZrO2/SiO2 and V2O5/ZrO2/SiO2 catalysts. Langmuir 1:3169–3178

Naumenko A, Gnatiuk Y, Smirnova N, Eremenko A (2012) Characterization of sol–gel derived TiO2/ZrO2 films and powders by Raman spectroscopy. Thin Solid Films 520:4541–4546

Picquart M, Lуpez T, Gуmez R, Torres E, Moreno A, Garcia J (2004) Dehydration and the crystallization process in sol-gel zirconia—thermal and spectroscopic study. J Therm Anal Calorim 76:755–761

Choi HC, Jung YM, Kim SB (2005) Size effects in the Raman spectra of TiO2 nanoparticles. Vibrational Spectrosc 37(1):33–38

Kim YK, Jang HM (2003) Polarization leakage and asymmetric Raman line broadening in microwave dielectric ZrTiO4. J Phys Chem Solids 64:1271–1278

Spanier JE, Robinson RD, Zhang F, Chan SW, Herman IP (2001) Size-dependent properties of CeO2-y nanoparticles as studied by Raman scattering. Phys Rev B 64:245407-1–245407-8

Zhu KR, Zhang MS, Chen Q, Yin Z (2005) Size and phonon-confinement effects on low-frequency Raman mode of anatase TiO2 nanocrystal. Phys Lett A 340(1−4):220–227

Wagner ChD, Naumkin AV, Kraut-Vass A, Allison JW, Powell CJ, Rumble JR (2012) NIST Standard Reference Database 20, Version 4.1. http://srdata.nist.gov/xps. Accessed 15 Sept 2012.

Ikawa H, Yamada T, Kojima K, Matsumoto S (1991) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of high- and low-temperature forms of zirconium titanate. J Am Ceram Soc 74:1459–1462

Sham EL, Aranda MAG, Farfan-Torres EM, Gottifredi JC, Martı’nez-Lara M, Bruque S (1998) Zirconium titanate from sol–gel synthesis: thermal decomposition and quantitative phase analysis. J Solid State Chem 139:225

Andrulevičius M, Tamulevičius S, Gnatyuk Y, Vityuk N, Smirnova N, Eremenko A (2008) XPS investigation of TiO2/ZrO2/SiO2 films modified with Ag/Au nanoparticles. Mat Sci (Medžiagotyra) 14(1):8, http://internet.ktu.lt/lt/mokslas/zurnalai/medz/pdf/medz0-92/02%20Electronic...(pp.08-14).pdf.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the European Community, Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013), Marie Curie International Research Staff Exchange Scheme (IRSES grant no. 612484), for the financial support of this work. The research was partly carried out with the equipment purchased thanks to the financial support of the European Regional Development Fund in the framework of the Polish Innovation Economy Operational Program (contract no. POIG.02.01.00-06-024/09 Center of Functional Nanomaterials).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

IS carried out the synthesis and characterization of nanocomposites by XRD method. DS and ADM participated in the XPS, Raman, and TEM-HRTEM studies. ES, OG, and WJ participated in the measurement of PSD for nanocomposites. OG and IS analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. VG and WJ designed the whole work and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sulym, I., Goncharuk, O., Sternik, D. et al. Silica-Supported Titania–Zirconia Nanocomposites: Structural and Morphological Characteristics in Different Media. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 111 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1304-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1304-1