Abstract

Thermal atomic layer deposition (ALD)-grown AlN passivation layer is applied on AlGaN/GaN-on-Si HEMT, and the impacts on drive current and leakage current are investigated. The thermal ALD-grown 30-nm amorphous AlN results in a suppressed off-state leakage; however, its drive current is unchanged. It was also observed by nano-beam diffraction method that thermal ALD-amorphous AlN layer barely enhanced the polarization. On the other hand, the plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD)-deposited SiN layer enhanced the polarization and resulted in an improved drive current. The capacitance-voltage (C-V) measurement also indicates that thermal ALD passivation results in a better interface quality compared with the SiN passivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistor (HEMT) is promising for high frequency, high power density, and high temperature applications owing to its superior material properties such as wide bandgap (3.4 eV), high breakdown field (2 × 106 V/cm), high thermal stability, and its 2-D electron gas (2DEG) channel [1, 2]. In order to realize GaN HEMTs on the mainstream 8-in. wafer, GaN-on-Si HEMTs have been intensively investigated. In the typical structure of GaN-on-Si HEMTs, the crystalline defect density is high because of the lattice mismatch of two material systems. The electron trapped at the AlGaN surface can cause surface leakage current and drain current collapse effects [2–4]. Therefore, passivation techniques have been widely applied for filling these traps [5–8].

ALD-grown AlN is a wide band-gap material recently reported as a new choice to passivate AlGaN/GaN HEMTs for its good isolation ability and high quality interface with AlGaN/GaN [3, 9]. However, most of the studies of the AlN passivation layer were grown by plasma-enhanced ALD (PEALD). In this work, we develop the thermal ALD technique and use it as a passivation layer. The plasma-free process leads to a simpler growth process and prevent possibly plasma-induced damage. A relatively larger film thickness is also applied to keep the traps on the new surface away from the 2DEG channel. For comparison, plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD)-deposited SiN passivation layer is also grown on AlGaN/GaN HEMTs. The output characteristics of devices using the two different passivation techniques are compared and discussed in this work.

Methods

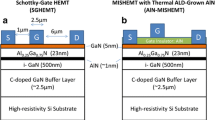

AlGaN/GaN HEMTs were fabricated on samples on Si(111) substrate with GaN buffer layer. A 25-nm Al0.25Ga0.75N layer barrier and a 3-nm undoped GaN cap layer were used. First, mesas were defined by BCl3/Ar-based reactive ion etching (RIE). After that, Ti/Al/Ni/Au (20/120/60/50 nm) stack were deposited by electron beam evaporation (EBE) followed by a rapid thermal anneal at 840 °C for 30 s to form the ohmic contact. Then, Schottky metal gates of Ni/Au (20/200 nm) were also deposited by EBE. The gate length, gate-to-drain spacing, gate-to-source spacing of fabricated HEMTs are all 1.5 μm. The output and transfer characteristics of the basic HEMT without passivation were then measured.

Finally, the passivation layer was deposited, and the contact windows were opened. The 30-nm AlN passivation layer was grown by BENEQ TFS200 ALD system with NH3 and trimethylaluminum precursors. During the reaction, the chamber is maintained at 400 °C. After the deposition of passivation layer, the contact windows were opened by RIE with BCl3/Ar. The device structure with passivation is shown in Fig. 1a. For comparison, the 110-nm SiN passivation layer was deposited by PECVD with N2/SiH4/NH3 at 350 °C. Then, the contact windows were opened by RIE with CF4. After that, the metal pads of Ni/Au (20/200 nm) for capacitance-voltage (C-V) measurements were deposited by EBE. The electrical characteristics were then collected and compared with the data before passivation. The capacitor structure using the passivation layer as dielectric layer is shown in Fig. 1b.

Results and Discussion

Figure 2 shows the output characteristics of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs with/without passivation layer. The drive current of SiN-passivated device increases obviously from 0.751 to 0.843 A/mm (VGS = 3 V, VDS = 5 V) while that of AlN-passivated device increases slightly from 0.738 to 0.759 A/mm (VGS = 3 V, VDS = 5 V).

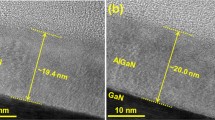

In order to explain the different behavior of devices using AlN and SiN passivation, nano-beam diffraction (NBD) was applied on the passivated device to detect the strain-caused deformation of AlGaN layer [10]. An unpassivated sample is used as the reference. The sampling positions of the AlN-passivated sample are shown in Fig. 3. Similar positions are chosen for the SiN-passivated samples. Figure 4 shows the overlapped NBD results at position “NBD2” indicated in Fig. 4. The compressed c axis of AlGaN in the SiN-passivated sample can be observed. While, the NBD results of AlN-passivated samples have no clear difference. The specific deformation results of all three positions in the two samples are compared with the reference and shown in Table 1. It can be seen that a tensile strain was applied on the AlGaN layer for the SiN-passivated sample, while almost no strain was detected applied on the AlGaN layer for the AlN-passivated samples.

Figure 5 shows the comparison of the transfer characteristic before/after AlN and SiN passivation. It can be seen that both two passivation techniques can suppress the off-state leakage. Wherein, the off-state current of AlN-passivated device dropped more significantly from 4.98 × 10−4 to 1.29 × 10−4 A/mm (VGS = −5 V, VDS = 4 V) than the SiN passivated one from 10.2 × 10−4 to 5.20 × 10−4 A/mm (VGS = −5 V, VDS = 4 V).

In Fig. 4, the drive current of AlN-passivated device is almost unchanged compared with the sample before AlN passivation. That means the increase of sheet concentration caused by the polarization-induced positive charge at the AlN/capGaN interface was not obvious [11]. As indicated in Table 1, the strain caused by the AlN passivation layer is negligible. In the previous work of Huang et al., crystalline AlN layer was used [9]. The band gap and charge concentration of amorphous AlN are both lower than the crystalline AlN [12, 13], so that there are lower polarization and fewer charges at the interface. However, the lower polarization also means higher barrier and lower leakage current at the AlN/cap-GaN interface. The leakage current of amorphous AlN layer is lower than crystalline AlN layer as well [14].

On the other hand, an enhancement of the drive current in the SiN-passivated devices is observed. Depending on the deposition conditions, the SiN deposition process can apply tensile or stress strain [15]. As shown in Table 1, the NBD analyses results indicate that a tensile strain was applied on the AlGaN layer. Therefore, piezoelectric polarization is enhanced, and the carrier density of 2DEG is increased [9, 16].

The ability of quick switch of the SiN-passivated sample, AlN-passivated sample, and unpassivated sample were tested. The VGS was pulsed from −6 to −2 V at VDS = 5 V, then the normalized response I D of the three samples were collected and shown in Fig. 6. The AlN-passivated sample performed best in quick switch, which indicated that it contains the fewest trapped charges to obstruct the gate control among these three samples.

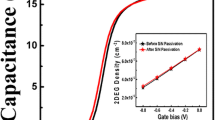

Capacitance-voltage (C-V) test was applied on the two types of passivation layers to detect the difference in filling interface traps and the qualities of passivation layers to describe this difference [17]. 30-nm thermal ALD-grown AlN and 30-nm PECVD-deposited SiN were tested.

Figure 7 shows the results of C-V test at 1 MHz frequency. The capacitor structure is shown in Fig. 1b. In Fig. 7b, a hysteretic effect was seen between the low-to-high and high-to-low voltage scan results of the SiN-passivated device. The hysteretic effect of C-V scanning results was caused by the unsealed interface traps and defects inside the passivation. In Fig. 7a, the C-V scan results of AlN-passivated device has no hysteretic effect. That means most of the interface traps were sealed by the AlN passivation layer.

Conclusions

The thermal ALD-grown amorphous AlN passivation layer owns a satisfactory interface state and film quality. This passivation technique performs better in sealing interface traps and reducing the off-state leakage than the PECVD-deposited SiN. Low polarization is observed for the thermal ALD-grown amorphous AlN passivation layer. Amorphous AlN is also promising as gate dielectric for AlGaN/GaN HEMT because of its predictable lower leakage than the crystalline one.

References

Pengelly RS, Wood SM, Milligan JW, Sheppard ST, Pribble WL (2012) A review of GaN on SiC high electron-mobility power transistors and MMICs. IEEE T Microw Theory, IEEE 60:1764–1783

Lee BH, Kim RH, Lim BO, Choi GW, Kim HJ, Ic Pyo H, Lee JH (2013) High RF performance improvement using surface passivation technique of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs at K-band application. Electron Lett 49:1013–1015

Koehler AD, Nepal N, Anderson TJ, Tadjer MJ, Hobart KD, Eddy CR Jr, Kub FJ (2013) Atomic layer epitaxy AlN for enhanced AlGaN/GaN HEMT passivation. Electron Device Letters, IEEE 34:1115–1117

Chen YH, Zhang K, Cao MY, Zhao SL, Zhang JC, Ma XH, Hao Y (2014) Study of surface leakage current of AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistors. Appl Phys Lett 104:153509

Xu D, Chu K, Diaz J, Zhu W, Roy R, Pleasant LM, Nichols K, Chao P-C, Xu M, Ye PD (2013) 0.2-μm AlGaN/GaN high electron-mobility transistors with atomic layer deposition Al2O3 passivation. Electron Device Letters, IEEE 34:744–746

Gatabi IR, Johnson DW, Woo JH, Anderson JW, Coan MR, Piner EL, Harris HR (2013) PECVD silicon nitride passivation of AlGaN/GaN heterostructures. T Electron Dev, IEEE 60:1082–1087

Kim H, Thompson RM, Tilak V, Prunty TR, Shealy JR, Eastman LF (2003) Effects of SiN passivation and high-electric field on AlGaN–GaN HFET degradation. Electron Device Letters, IEEE 24:421–423

Jeon CM, Lee J-L (2005) Effects of tensile stress induced by silicon nitride passivation on electrical characteristics of heterostructure field-effect transistors. Appl Phys Lett 86:172101

Huang S, Jiang Q, Yang S, Zhou C, Chen KJ (2012) Effective passivation of AlGaN/GaN HEMTs by ALD-grown AlN thin film. Electron Device Letters, IEEE 33:516–518

Usuda K, Numata T, Irisawa T, Hirashita N, Takagi S (2005) Strain characterization in SOI and strained-Si on SGOI MOSFET channel using nano-beam electron diffraction (NBD). Mat Sci Eng B 124–125:143–147

Huang S, Jiang Q, Yang S, Tang Z, Chen KJ (2013) Mechanism of PEALD-grown AlN passivation for AlGaN/GaN HEMTs: compensation of interface traps by polarization charges. Electron Device Letters, IEEE 34:193–195

Harris H, Biswas N, Temkin H, Gangopadhyay S, Strathman M (2001) Plasma enhanced metalorganic chemical vapor deposition of amorphous aluminum nitride. J Appl Phys 90:5825–5831

Kar JP, Bose G, Tuli S (2005) Influence of rapid thermal annealing on morphological and electrical properties of RF sputtered AlN films. Mat Sci Semicon Proc 8:646–651

Aardahl CL, Rogers JW, Yun HK, Ono Y, Tweet DJ, Hsu ST (1999) Electrical properties of AlN thin films deposited at low temperature on Si (100). Thin Solid Films 346:174–180

Fan R, Hao Z-B, Lei W, Lai W, Li H-T, Yi L (2010) Effects of SiN on two-dimensional electron gas and current collapse of AlGaN/GaN high electron mobility transistors. Chinese Physics B 19:017306

Ambacher O, Foutz B, Smart J, Shealy JR, Weimann NG, Chu K, Murphy M, Sierakowski AJ, Schaff WJ, Eastman LF, Dimitrov R, Mitchell A, Stutzmann M (2000) Two dimensional electron gases induced by spontaneous and piezoelectric polarization in undoped and doped AlGaN/GaN heterostructures. J Appl Phys 87:334

Schroder DK (2006) Semiconductor material and device characterization, third edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, Hoboken, Chapter 6

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant 61322404), Shanghai 13DZ1108100, and in part by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (Grant 2013ZX02308004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

SXZ designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. XYL, LQZ, and HFH participated in the preparation of the devices. JSS and PFW supervised this study. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, SX., Liu, XY., Zhang, LQ. et al. Impacts of Thermal Atomic Layer-Deposited AlN Passivation Layer on GaN-on-Si High Electron Mobility Transistors. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 137 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1335-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1335-7