Abstract

Hierarchical heterostructures of NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) were developed as an electrode material for supercapacitor with improved pseudocapacitive performance. Within these hierarchical heterostructures, the mesoporous NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays directly grown on the Ni foam can not only act as an excellent pseudocapacitive material but also serve as a hierarchical scaffold for growing NiMoO4 or CoMoO4 electroactive materials (nanosheets). The electrode made of NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 presented a highest areal capacitance of 3.74 F/cm2 at 2 mA/cm2, which was much higher than the electrodes made of NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 (2.452 F/cm2) and NiCo2O4 (0.456 F/cm2), respectively. Meanwhile, the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode exhibited good rate capability. It suggested the potential of the hierarchical heterostructures of NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 as an electrode material in supercapacitors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

To meet the increasing requirement for portable electronics, hybrid electronic vehicles and other micro- and nanodevices, numerous studies have been carried out to develop many kinds of energy storage systems. As an important energy storage device, the widely studied supercapacitors, also known as electrochemical capacitors, have been believed as a promising candidate due to their high specific power, long cycling life, fast charge and discharge rates, and reliable safety [1–9]. Though these supercapacitors demonstrated these distinctive advantages, as compared with the batteries and fuel cells, the relatively lower energy densities seriously block their large-scale practical application [4, 10]. So far, various electrode materials which include carbon materials [11, 12], transition metal oxides [2, 13–15], and conducting polymers [16, 17] have been designed and synthesized to enhance the electrochemical properties for the practical applications in the supercapacitors.

Recently, some bimetallic oxides, such as NiCo2O4 [15, 17–20], ZnCo2O4 [21, 22], NiMoO4 [23], and CoMoO4 [24, 25], have been developed as a new electrode material used for supercapacitors because of their excellent electrical conductivity and multiple oxidation states (as compared with the binary metal oxides) for reversible Faradaic reactions [26]. For fully utilizing the advantages of active materials and thus optimizing the performance of these materials, plenty of efforts has been devoted, i.e., realizing additive/binder-free electrode architectures, which eliminate the “dead surface” and release complicated process in traditional slurry-coating electrode and meaningfully improve the utilization rate of electrode materials even at high rates [4, 27], constructing 3D hierarchical heterostructures, which can provide efficient and fast pathways for electron and ion transport [20, 28], and exploring smart integrated array architectures with rational multi-component combination, which can achieve the synergistic effect from all individual constituents [29–31]. Taken some successful examples, CoxNi1 − xDHs/NiCo2O4/CFP composite electrodes were prepared by a hydrothermal route and an electrodeposition process, showing high capacitance of ∼1.64 F/cm2 at 2 mA/cm2, good rate capability, and excellent cycling stability [20]; 3D hierarchical NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 core-shell nanowire/nanosheet arrays delivered a high areal capacitance of 5.80 F/cm2 at 10 mA/cm2, excellent rate capability, and high cycling stability [32]. Despite these notable achievements, it is still a hard task to design and construct 3D hierarchical heterostructures made of the bimetallic oxides with improved electrochemical properties for the supercapacitors.

Herein, we report hydrothermal growth of hierarchical heterostructures of NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) as an electrode material for the supercapacitors with improved performances. Within these hierarchical heterostructures, high electrochemical activity of NiCo2O4 not only shows outstanding pseudocapacity but also can be regarded as a backbone to provide reliable electrical connection to the XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co). Between them, the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode material showed a highest areal capacitance of 3.74 F/cm2 at 2 mA/cm2, which was much higher than the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 electrode material (2.452 F/cm2), and good rate capability, implying its prospect as an alternative electrode material in the supercapacitors.

Methods

Synthesis of NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) Composite Nanosheet Arrays

All the reactants here were analytically graded and used without further purification. The synthesis of the composite nanosheet arrays was described briefly as follows: Firstly, the NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays were grown on the Ni foam according to a reference [17]. Secondly, the product of as-grown NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays was put into a 60-mL Teflon-lined autoclave, which contained 0.5 mmol of NiCl2·6H2O (or CoCl2·6H2O), 0.5 mmol of Na2MoO4·2H2O, and 50 mL of deionized water. The autoclave was sealed and maintained at 120 °C for 2 h (or 1 h) in an electric oven and then cooled down to room temperature. The NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) composites on the Ni foam were carefully washed with deionized water and absolute ethanol, successively, and then dried at 60 °C overnight. Lastly, the samples were annealed at 400 °C for 1 h at a ramping rate of 1 °C/min.

Material Characterizations

As-synthesized products were characterized by means of a D/max-2550 PC X-ray diffractometer (XRD; Rigaku, Cu-Kα radiation), a scanning electron microscopy (SEM; S-4800), and a transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-2100 F) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDX).

Results and Discussion

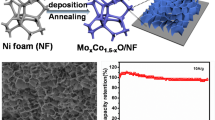

In this work, the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) hierarchical heterostructures were successfully synthesized for electrode materials. As depicted schematically in Fig. 1, the synthesis process includes two steps: the hydrothermal growth of NiCo2O4 nanosheets on the Ni foam and subsequent annealing as the first step and the hydrothermal growth of NiMoO4 or CoMoO4 nanosheets (coatings) on the NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays and another annealing process as the second step. Herein, 3D Ni foam, with uniform macropore structure, huge supporting area, and high electrical conductivity, was selected as a current collector for the growth of electrode materials, which can provide efficient electrolyte penetration to enable fast ion diffusion [27, 33]. Meanwhile, the NiCo2O4 nanosheets grown uniformly on Ni foam functioned as the backbone to support and give reliable electrical connection to XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) nanosheets, which can contribute to electronic and ionic diffusion and improve the utilization rate of electrode material. More importantly, the NiCo2O4 electrode material with high electrochemical activity can also act as active materials for charge storage and contribute to the capacitance.

Combining the hydrothermal reaction and the annealing process resulted in the NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays grown on Ni foam. Detailed morphology and microstructure of the NiCo2O4 nanosheets were investigated via the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figure 2a, b shows the highly tight NiCo2O4 nanosheets (with a thickness of ~30–50 nm) that grew uniformly and vertically on the Ni foam and interconnected with each other, resulting in a highly porous structure with an abundant open space. Figure 2c shows a NiCo2O4 nanosheet almost transparent to electron beam, suggesting an ultrathin feature. Intriguingly, numerous mesoporous arrays are distributed uniformly throughout the whole NiCo2O4 nanosheet. The nanosheet arrays were scratched from the Ni foam and were then characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) to determine the crystalline phase of the product. As shown in Fig. 2d, all well-defined diffraction peaks can be indexed to the cubic phase NiCo2O4 by referring to the JCPDS card (no. 20-0781).

The NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays grown on the Ni foam act as an ideal scaffold to load additional electroactive pseudocapacitive materials, thus enhancing the electrochemical performance. Considering this merit, NiMoO4 or CoMoO4 nanosheets were grown on the surface of the NiCo2O4 nanosheets via a hydrothermal reaction and an annealing step similar to the first growth step described above, forming NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 composite nanosheet arrays (a core-shell structure or shaped like caterpillar). Figure 3a, b shows SEM images of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 composite nanosheet arrays, in which the ultrathin NiMoO4 nanosheets were uniformly grown on the surface of NiCo2O4 nanosheets and thus plenty of the space among NiCo2O4 nanosheets is utilized abundantly, and a thickness of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 composite nanosheets is in the range of ~250–300 nm. Importantly, the integration of the NiMoO4 material into the original NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays does not destroy the ordered structure. In addition, these NiMoO4 nanosheets are interconnected with each other to form a highly porous morphology, which can provide more active sites for electrolyte ions to transport efficiently. Figure 3c shows the TEM image of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 composites. The result shows that the NiMoO4 nanosheets are highly dense but still do not cover the entire mesoporous NiCo2O4 nanosheets fully. Moreover, energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrum (Fig. 3d) indicates that Ni, Co, Mo, and O can be detected in the composites. Surely, the Cu and C signals come from the carbon-supported Cu grid.

Figure 4 shows the SEM images of the samples, prepared via a different hydrothermal reaction time. It is used to demonstrate the formation process of the samples. Figure 4a depicts the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 nanosheet arrays formed via 0.5 h of the hydrothermal reaction. It can be seen that the nanosheets’ surface of NiCo2O4 loses their original smooth appearance and was interspersed by many fine NiMoO4 nanosheets. Then, the reaction time was extended to 1 h and the SEM image (Fig. 4b) showed the results. Almost all the naked surface observed before was fully coated by NiMoO4 nanosheets with the thickness increased to ~100–150 nm. As the time of the hydrothermal reaction becomes longer, the composition becomes thicker and at last the whole thickness in Fig. 4d is ~400–500 nm, which leads to a much smaller interspace among the adjacent sheets. But the growth of mass NiMoO4 nanosheets on the NiCo2O4 nanosheets may decay the utilization of the NiCo2O4 (core) materials and even some NiMoO4 (shell) materials may be blocked from the access to electrolyte. Therefore, the hydrothermal reaction time should be optimized (e.g., 2 h) to get an improved electrochemical properties.

Hierarchical heterostructures of the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 composite nanosheets were also fabricated as a comparison with the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 nanosheet arrays for their usage as an electrode material. Figure 5a, b shows the SEM image of the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 composite nanosheets. It clearly confirms that the whole surface of the NiCo2O4 nanosheets is homogeneously covered by the CoMoO4 nanosheets, and the uniformity of these structures is similar to that of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 nanosheet arrays. As the TEM image (Fig. 5c) demonstrates, the thickness of the CoMoO4 nanosheets is about 20–50 nm. Additionally, the composition of the as-synthesized NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 composites was confirmed by EDX. As shown in Fig. 5d, the peaks of Cu and C derive from the Cu grid, and the strong signals of Ni, Co, Mo, and O further ascertain the formation of NiCo2O4@CoMoO4.

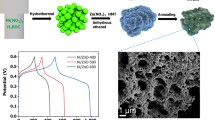

Then, the electrochemical properties of the hierarchical heterostructures of the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) were investigated to evaluate their applicability as an active material for the supercapacitors, where a three-electrode cell with a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) reference electrode, a Pt counter electrode, and a KOH aqueous electrolyte (3 M) inside was used. As a comparison, the cyclic voltammogram (CV) curves from three electrodes made from NiCo2O4 and NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) materials, respectively, were shown in Fig. 6a. It was recorded with a potential window ranging from 0 to 0.6 V and a scan rate of 5 mV/s. Deduced from the CV curves’ shape, the Faradaic redox reactions associated with M-O/M-O-OH (M = Ni, Co) dominated the capacitance characteristics [18, 20] of these electrodes. Obviously, the surface area of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode is higher than that of the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 electrode and NiCo2O4 electrode, suggesting that the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode possessed a greater capacitance than the other two. The high capacitance of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode is mainly attributed to the fact that a highly porous nanostructure that originated from numerous ultrathin NiMoO4 nanosheets grown on the NiCo2O4 nanosheet surface should provide more active sites for increasing electrolyte ion transportation efficiency to enhance the utilization of the whole electrode. Also, the CV curves of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrodes taken via a various scan rate, i.e., 5, 10, 20, and 30 mV/s, were collected, as shown in Fig. 6b. It was noted that the peak position shifted slightly with the increase of scan rate, implying a good capacitive behavior and a high-rate capability of the electrode material. The galvanostatic charge-discharge (CD) method was applied to compare the capacitive ability of the NiCo2O4 electrode and two composite electrodes of NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 and NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 at the same current density of 2 mA/cm2, as illustrated in Fig. 6c. It was found that the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode possessed a longer discharging time than the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 and pure NiCo2O4 electrodes, demonstrating that such an electrode has an enhanced capacitance. Moreover, the areal capacitance of the electrode materials could be calculated from their CD curves by this equation: C = (I · t)/(S · ΔV), where I (A) is the current for the charge-discharge measurement, t (s) is the discharge time, S is the geometrical area of the electrode [31], and ΔV (V) is the voltage interval of the discharge. As shown in Fig. 6d, the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode always exhibited higher areal capacitances than the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 and NiCo2O4 electrodes. The maximal areal capacitance of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode was found to be 3.74 F/cm2 at 2 mA/cm2, which is much higher than the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 electrode (2.45 F/cm2), and 8 times higher than the NiCo2O4 electrode (0.46 F/cm2). In particular, the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode still has an areal capacitance of 2.46 F/cm2 even if the current density increased to 30 mA/cm2, retaining appropriately 66 % of its initial value. However, the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 electrode and the NiCo2O4 electrode only showed the areal capacitance of 1.17 and 0.27 F/cm2 at a high current density of 30 mA/cm2, respectively.

a CV curves of the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) and NiCo2O4 electrodes at a scan rate of 5 mV/s. b CV curves of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode at a various scan rate, i.e., 5, 10, 20, and 30 mV/s. c CD curves of the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) and NiCo2O4 electrodes collected at a current density of 2 mA/cm2. d Areal capacitance of the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) and the NiCo2O4 electrodes calculated from the CD curves as a function of current density

Figure 7 shows the cycling performance of the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) composite electrodes, which was evaluated through 2000 cycles with a scan rate of 60 mV/s. After 2000 cycles, it is found that the total capacitance retention was ~95.5 % for the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 electrode and ~83.1 % for the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode, respectively. Compared with the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 electrodes, the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrode did not show a better cycling stability, but the characteristics of the high-rate capability and the large areal capacitance make the hierarchical heterostructures of the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 a more prospective electrode material. The outstanding capacitive properties of the hierarchical heterostructures of the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) electrode are considered to originate from the synergistic effect of its following distinctive compositional and topological features [34–36]. First, within the hierarchical heterostructures, both core and shell are active materials, and the core-shell heterostructures enable easy access of electrolyte. Therefore, both of them can effectively contribute to the capacity. Secondly, the NiCo2O4 is highly conductive, which can provide “superhighways” for the charge in the core-shell structure. The direct growth of the XMoO4 nanosheets on the NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays avoids the use of polymer binder/conductive additives and further guarantees the effective charge transport between them. Besides, the high electrical conductivity could decrease the charge transfer resistance of the electrodes, thus leading to an increased power density. Finally, the XMoO4 nanosheets and the NiCo2O4 nanosheets are mesoporous that increases the electroactive sites.

Conclusions

In conclusion, 3D hierarchical heterostructures of the NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) composite nanosheet arrays have been successfully designed and prepared for the supercapacitors. In such a novel nanostructure, the mesoporous NiCo2O4 nanosheet arrays grown directly on the Ni foam not only acted as a good pseudocapacitive material but also used as a hierarchical framework for loading NiMoO4 or CoMoO4 electroactive material. Notably, the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 composite electrode showed excellent rate capability as well as a highest areal capacitance of 3.74 F/cm2 at 2 mA/cm2, which was much higher than the values for the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 electrode (2.452 F/cm2) and NiCo2O4 electrode (0.456 F/cm2). The total capacitance retention of the NiCo2O4@CoMoO4 and NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 electrodes after 2000 cycles is ~95.5 and ~83.1 %, respectively. Based on these electrochemical properties, the NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 composite electrode material may be more appropriate for practical applications.

References

Simon P, Gogotsi Y (2008) Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat Mater 7:845

Wang GP, Zhang L, Zhang JJ (2012) A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Chem Soc Rev 41:797

Liu C, Li F, Ma LP, Cheng HM (2010) Advanced materials for energy storage. Adv Mater 22:E28

Lu XH, Yu MH, Zhai T, Wang GM, Xie SL, Liu TY et al (2013) High energy density asymmetric quasi-solid-state supercapacitor based on porous vanadium nitride nanowire anode. Nano Lett 13:2628

Shen LF, Wang J, Xu GY, Li HS, Dou H, Zhang XG (2015) NiCo2S4 nanosheets grown on nitrogen-doped carbon foams as an advanced electrode for supercapacitors. Adv Energy Mater 5:1400977

Liu XY, Shi SJ, Xiong QQ, Li L, Zhang YJ, Tang H et al (2013) Hierarchical NiCo2O4@NiCo2O4 core/shell nanoflake arrays as high-performance supercapacitor materials. ACS Appl Mater Inter 5:8790

Bao FX, Zhang ZQ, Guo W, Liu XY (2015) Facile synthesis of three dimensional NiCo2O4@MnO2 core-shell nanosheet arrays and its supercapacitive performance. Electrochim Acta 157:31

Li YH, Zhang YF, Li YJ, Wang ZY, Fu HY, Zhang XN et al (2014) Unveiling the dynamic capacitive storage mechanism of Co3O4@NiCo2O4 hybrid nanoelectrodes for supercapacitor applications Electrochim Acta 145:177

Liu XY, Zhang YQ, Xia XH, Shi SJ, Lu Y, Wang XL et al (2013) Self-assembled porous NiCo2O4 hetero-structure array for electrochemical capacitor. J Power Sources 239:157

Zhao JW, Chen JL, Xu SM, Shao MF, Zhang Q, Wei F et al (2014) Hierarchical NiMn layered double hydroxide/carbon nanotubes architecture with superb energy density for flexible supercapacitors. Adv Funct Mater 24:2938

Yan J, Fan ZJ, Sun W, Ning GQ, Wei T, Zhang Q et al (2012) Advanced asymmetric supercapacitors based on Ni(OH)2/graphene and porous graphene electrodes with high energy density. Adv Funct Mater 22:2632

Lin TQ, Chen IW, Liu FX, Yang CY, Bi H, Xu FF et al (2015) Nitrogen-doped mesoporous carbon of extraordinary capacitance for electrochemical energy storage. Science 350:1509

Yang PH, Ding Y, Lin ZY, Chen ZW, Li YZ, Qiang PF et al (2014) Low-cost high-performance solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors based on MnO2 nanowires and Fe2O3 nanotubes. Nano Lett 14:731

Zhang ZY, Chi K, Xiao F, Wang S (2015) Advanced solid-state asymmetric supercapacitors based on 3D graphene/MnO2 and graphene/polypyrrole hybrid architectures. J Mater Chem A 3:12828

Wang X, Yan CY, Sumboja A, Lee PS (2014) High performance porous nickel cobalt oxide nanowires for asymmetric supercapacitor. Nano Energy 3:119

Xia XH, Chao DL, Fan ZX, Guan C, Cao XH, Zhang H et al (2014) A new type of porous graphite foams and their integrated composites with oxide/polymer core/shell nanowires for supercapacitors: structural design, fabrication, and full supercapacitor demonstrations. Nano Lett 14:1651

Xu KB, Huang XJ, Liu Q, Zou RJ, Li WY, Liu XJ et al (2014) Understanding the effect of polypyrrole and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) on enhancing the supercapacitor performance of NiCo2O4 electrodes. J Mater Chem A 2:16731

Yuan CZ, Li JY, Hou LR, Zhang XG, Shen LF, Lou XW (2012) Ultrathin mesoporous NiCo2O4 nanosheets supported on Ni foam as advanced electrodes for supercapacitors. Adv Funct Mater 22:4592

Jiang H, Ma J, Li CZ (2012) Hierarchical porous NiCo2O4 nanowires for high-rate supercapacitors. Chem Commun 48:4465

Huang L, Chen DC, Ding Y, Feng S, Wang ZL, Liu ML (2013) Nickel-cobalt hydroxide nanosheets coated on NiCo2O4 nanowires grown on carbon fiber paper for high-performance pseudocapacitors. Nano Lett 13:3135

Chuo HX, Gao H, Yang Q, Zhang N, Bu WB, Zhang XT (2014) Rationally designed hierarchical ZnCo2O4/Ni(OH)2 nanostructures for high-performance pseudocapacitor electrodes. J Mater Chem A 2:20462

Liu B, Zhang J, Wang XF, Chen G, Chen D, Zhou CW et al (2012) Hierarchical three-dimensional ZnCo2O4 nanowire arrays/carbon cloth anodes for a novel class of high-performance flexible lithium-ion batteries. Nano Lett 12:3005

Guo D, Luo YZ, Yu XZ, Li QH, Wang TH (2014) High performance NiMoO4 nanowires supported on carbon cloth as advanced electrodes for symmetric supercapacitors. Nano Energy 8:174

Yang F, Zhao YL, Xu X, Xu L, Mai LQ, Luo YZ (2011) Hierarchical MnMoO4/CoMoO4 heterostructured nanowires with enhanced supercapacitor performance. Nat Commun 2:381

Yu XZ, Lu BG, Xu Z (2014) Super long-life supercapacitors based on the construction of nanohoneycomb-like strongly coupled CoMoO4-3D graphene hybrid electrodes. Adv Mater 26:1044

Yuan CZ, Wu HB, Xie Y, Lou XW (2014) Mixed transition-metal oxides: design, synthesis, and energy-related applications. Angew Chem Int Ed 53:1488

Zhou C, Zhang YW, Li YY, Liu JP (2013) Construction of high-capacitance 3D CoO@polypyrrole nanowire array electrode for aqueous asymmetric supercapacitor. Nano Lett 13:2078

Xiao JW, Wan L, Yang SH, Xiao F, Wang S (2014) Design hierarchical electrodes with highly conductive NiCo2S4 nanotube arrays grown on carbon fiber paper for high-performance pseudocapacitors. Nano Lett 14:831

Yu GH, Xie X, Pan LJ, Bao ZN, Cui Y (2013) Hybrid nanostructured materials for high-performance electrochemical capacitors. Nano Energy 2:213

Liu JP, Jiang J, Cheng CW, Li HX, Zhang JX, Gong H et al (2011) Co3O4 nanowire@MnO2 ultrathin nanosheet core/shell arrays: a new class of high-performance pseudocapacitive materials. Adv Mater 23:2076

Xu J, Wang QF, Wang XW, Xiang QY, Liang B, Chen D et al (2013) Flexible asymmetric supercapacitors based upon Co9S8 nanorod//Co3O4@RuO2 nanosheet arrays on carbon cloth. ACS Nano 7:5453

Cheng D, Yang YF, Xie JL, Fang CJ, Zhang GQ, Xiong J (2015) Hierarchical NiCo2O4@NiMoO4 core-shell hybrid nanowire/nanosheet arrays for high-performance pseudocapacitors. J Mater Chem A 3:14348

Yan T, Li RY, Zhou L, Ma CY, Li ZJ (2015) Three-dimensional electrode of Ni/Co layered double hydroxides@NiCo2S4@graphene@Ni foam for supercapacitors with outstanding electrochemical performance. Electrochimica Acta 176:1153

Zou RJ, Yuen MF, Yu L, Hu JQ, Lee CS, Zhang WJ (2016) Electrochemical energy storage application and degradation analysis of carbon-coated hierarchical NiCo2S4 core-shell nanowire arrays grown directly on graphene/nickel foam. Sci Rep 6:20624

Zou RJ, Zhang ZY, Yuen MF, Sun ML, Hu JQ, Lee CS, Zhang WJ (2015) Three-dimensional networked NiCo2S4 nanosheet arrays/carbon cloth anodes for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. NPG Asia Materials 7:e195

Zou RJ, Zhang ZY, Yuen MF, Hu JQ, Lee CS, Zhang WJ (2015) Dendritic heterojunction nanowire arrays for high-performance supercapacitors. Sci Rep 5:7862

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank the Institute of Functional Nano & Soft Materials (FUNSOM) for supporting our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

JH designed and performed the experiments. JH, GS, and FQ prepared the samples and analyzed the data. JH, GS, FQ, and LW participated in interpreting and analyzing the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, J., Qian, F., Song, G. et al. Hierarchical Heterostructures of NiCo2O4@XMoO4 (X = Ni, Co) as an Electrode Material for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 257 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1475-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1475-9