Abstract

N–Cu-activated carbon (AC)/TiO2 nanoparticles were prepared by the sol-gel technique through microwave irradiation to modify the visible-light response of TiO2. Their structure, surface chemical composition, and optical absorption properties were characterized. The results showed that the codoped particles had a higher surface area and smaller particle size than pure AC/TiO2 and monodoped AC/TiO2. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy of N–Cu-AC/TiO2 showed that Cu atoms replaced Ti atom sites, whereas N atoms occupied the O atom sites and interstitial sites in the TiO2 lattice, which changed the electric and band-gap structures of the photocatalyst. N or Cu monodoping of AC/TiO2 reduced the energy band gap of TiO2 from 2.86 eV to 2.81 or 2.61 eV, respectively. In (N, Cu)-codoped AC/TiO2, N and Cu were incorporated into the TiO2 framework and narrowed the band gap of TiO2 to 2.47 eV, causing a large red shift and enhancing visible-light utilization efficiency. Photocatalytic activities were further examined by formaldehyde degradation under visible-light irradiation. N–Cu-AC/TiO2 was found to have the highest activity (ca. 94.4 % formaldehyde degradation efficiency) and to be easily recyclable. These results show an important and innovative method of improving AC/TiO2 activity by modifying the nonmetallic and metallic species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nanocrystalline TiO2 has potential for application to photocatalytic degradation of harmful pollutants dispersed in the environment because of its relatively low cost, nontoxicity, favorable optoelectronic properties, and excellent chemical stability [1, 2]. However, the photocatalytic activity and utilization efficiency of visible light are limited because of the small specific surface area and large band gap (3.2 eV) of pure TiO2 [3–5]. Adsorption can be increased by preparing a porous material-loaded TiO2 photocatalyst, and this has drawn much attention. Given that activated carbon (AC) has a large specific surface area, the reaction rate constant of AC/TiO2 is high for the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants [6]. In the work of Pastravanu et al., 92 % methyl orange conversion was achieved after 170 min irradiation using AC/TiO2 with a large surface area of 357 cm2/g [7].

TiO2 doping with transition metals has been widely investigated to modify the band gap of TiO2 to absorb visible light. Nagaveni et al. [8] reported that Cu2+-, V5+-, Fe3+-, and Zr4+-doped TiO2 exhibited improved performance in the photodegradation of 4-nitrophenol compared with commercial TiO2. Among the various metals doped into TiO2, Cu has been considered the most important because of the narrow band-gap energies of its oxides (cupric oxide, CuO, possesses 1.4 eV and cuprous oxide, Cu2O, possesses 2.2 eV) and their large light absorption coefficients [9–12]. In addition, Cu doping can reduce the band gap of TiO2 to an appropriate value for visible-light adsorption and can reduce the electron-hole recombination rate during photocatalysis. Wang et al. [13] reported that a Cu-doped TiO2 thin film exhibited much improved photocatalytic activity compared with pure TiO2 thin film in the degradation of a 10 mg/L methylene blue solution under simulated solar-driven irradiation. In recent years, significant efforts have been made to dope TiO2 with nonmetallic anions, such as N, S, and C, all of which replace O in the TiO2 lattice to generate energy levels just above the top of the TiO2 valence band [14–16]. In terms of performance, nitrogen doping is undoubtedly the most impressive solution for improving the visible-light response of TiO2 [17–20]. Recently, the concept of second-generation TiO2-based materials has been introduced, wherein codoping with two dopant elements produces a synergistic effect to enhance the visible-light absorption efficiency and reduce the recombination processes of the photogenerated charges [21–24]. A Ag/N-codoped TiO2 system was prepared using a sonication-assisted sol-gel method by Mothi et al. [25] who found that the system was highly active for the photoconversion of 9-(N,N-dimethylaminomethyl) anthracene.

Microwave-assisted preparation of catalytic materials is gaining increased attention [26]. This method is an efficient alternative because it allows swift heating to the required temperature and extremely rapid rates of crystallization, leading to simplification of the preparation procedure [27–29]. However, codoping Cu and N to TiO2 to reduce its band gap and load it onto the AC through a microwave-assisted method has rarely been reported. Thus, an important and innovative method has been attempted to enhance the photodegradation activity of AC/TiO2 with visible-light response via modification with Cu and N through microwave irradiation.

In the present paper, AC/TiO2, N, Cu-monodoped AC/TiO2 and N/Cu-codoped AC/TiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized by a sol-gel method under microwave assistance. The phase structure, morphology, specific surface area, and optical properties were investigated using a variety of techniques. Studies on the use of catalysts for photodegradation of HCHO in aqueous solution under visible-light irradiation are also in progress. The concept used in this research can be further applied to modify other materials for improved photocatalytic performance.

Main Text

Experimental Methods

Catalyst Preparation

AC was prepared by the means described in a previous study [30]. The obtained AC samples were pretreated by addition to HNO3 solution, then being left for 24 h. The mixture was filtered using distilled water until it became neutral. The pretreated AC was then dried and stored until use. All reagents were of analytical grade. The TiO2 gel/sol was obtained by the conventional sol-gel method [31]. In typical synthesis process, 30 mL of tetrabutyl orthotitanate (TBOT) was dissolved in anhydrous alcohol (EtOH) in proportion of 1:1 (volume ratio). This solution was thoroughly stirred for 40 min and named solution A. Solution B was prepared by mixing 14 mL of glacial acetic acid and 7 mL of distilled water in 35 mL of absolute alcohol. Solution B was added to solution A dropwise and continuously stirred for 1 h. A clear, pale-yellow TiO2 sol was then obtained. Pretreated AC (10 g) was added to TiO2 sol (100 g). The mixture was placed in an air-dry oven at 100 °C for 24 h. After solidification, AC/TiO2 was prepared under microwave irradiation at 700 W for 15 min. To prepare Cu-doped AC/TiO2, 0.44 g of Cu(NO3)2 was mixed with solution B, while for N-doped AC/TiO2, 1.71 g of urea was dissolved in solution B. The doped N and Cu in the samples of N-AC/TiO2 and N–Cu-AC/TiO2 were 0.04 g and 0.01 g, respectively. For N, Cu-codoped AC/TiO2, the sample was noted as 0.04 N-0.01 Cu-AC/TiO2.

Catalyst Characterization

The crystal structures of the prepared samples were measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Rigaku D/Max-2500/PC powder diffractometer. Each sample was scanned using Cu-Kα radiation with an operating voltage of 40 kV and an operating current of 200 mA. The surface micromorphology of the photocatalyst was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; S4800, Hitachi Ltd.) at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed on a Tecnai G2 F20 microscope at 100 kV. FTIR spectra were recorded with a Bruker Vertex FTIR spectrometer, resolution of 2 cm−1, in the 4000–400-cm−1 range by the KBr pellet technique. UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra were obtained with a powder UV-vis spectrophotometer (U-4100, Hitachi Ltd.). The specific surface area (SBET, m2/g) was calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) equation. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis of the samples was conducted using a PHI5700 ESCA system equipped with an Mg Kα X-ray source (1253.6 eV) under a vacuum pressure <10−6 Pa. The formation rate of ⋅OH at the photo-illuminated sample/water interface was detected by photoluminescence (PL) using terephthalic acid (TA) as a probe molecule. PL spectroscopy of the synthesized products was undertaken at room temperature on a Hitachi F2500 spectrofluorometer using a Xe lamp with an excitation wavelength of 325 nm.

Photocatalytic Activity

The photocatalytic activity of prepared photocatalyst was measured by degrading the HCHO solution. In a typical test, 50 mg of catalyst was added to 50 mL of HCHO solution (30 mg/L, pH = 6.8). The mixture was then irradiated under a 500 W Xe lamp (any irradiation below 420 nm was removed by using a cut-off filter) to degrade HCHO. The distance between the reactor and lamp housing was 8.5 cm. The concentration of HCHO was measured using an ultraviolet visible spectrophotometer under the maximum absorption wavelength of 413 nm. The removal efficiency, η, of the photocatalyst can be calculated as follows:

where C o and C t are the concentrations of HCHO at initial and different irradiation times, respectively.

The rate of ·OH in the photocatalytic reactions was evaluated by adding 50 mL of terephthalic acid in a manner similar to the above photodegradation experiment. For terephthalic acid, to ensure solubility, solutions were prepared in dilute (2 × 10−3 mol/L) NaOH solution. Photocatalyst in the solution was magnetically stirred and illuminated under visible-light irradiation. The photocatalytic experiment was carried out in the presence of 2 mL (10.66 mol/L) t-BuOH, a radical scavenger [32].

Discussion

XRD and BET Characterization

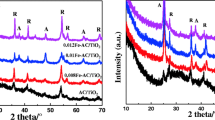

The XRD patterns of the different samples are presented in Fig. 1. The peaks observed at 25.3°, 38°, and 48° represent the anatase crystalline phase, and the peaks at 27.42°, 36.2°, 41.3°, and 44.2° represent the rutile crystalline phase. These all agree with previously reported values [5]. It can be seen that the TiO2 crystals obtained via the microwave radiation method with only 15 min, which is conducive to stabilize the AC structure and makes for a more energy-efficient process compared with the traditional heating method [7]. In addition, an additional peak at 43.3°, corresponding to a Cu species, was obtained when Cu was codoped, indicating the formation of Cu0 [9]. The Cu0 was formed according to the following chemical reaction [14]:

The XRD patterns show that both the monodoped and codoped AC/TiO2 can prevent the phase transformation process from anatase TiO2 to rutile from occurring, as shown in Table 1. This may be favorable with respect to degradation of the catalyst [33]. The average crystal sizes of the nanoparticles have been obtained from the Scherrer equation:

where D is the average crystallite diameter (nm), k is the X-ray wavelength, θ is the Bragg angle, and β is the line broadening at half the maximum intensity. The mean crystallite sizes of the doped-TiO2 are slightly smaller than that of its precursor (Table 1). In the codoped AC/TiO2, the entrance of Cu2+ (0.72 Å) into the TiO2 crystal lattice to substitute Ti4+ (0.68 Å) produces strain through lattice distortions [4], whereas when N− replaces O2− ions, it creates oxygen deficiencies in the TiO2 lattice. These features allow the rearrangement of Ti4+ and O2− ions in the lattice to interfere with the crystallite growth mechanism and phase transformation [14]. The specific surface area of the catalyst also has an important effect on the degradation of organic compounds because of the synergistic effect of AC and TiO2 [31]. The BET surface areas of the AC/TiO2 before and after doping were measured by N2 adsorption/desorption (Fig. 2) at a liquid N2 temperature of 78 K, as shown in Table 1. The doping of ions has little effect on the surface area of activated carbon, and the N–Cu-AC/TiO2 maintained a large surface area of 548 m2/g.

Morphology of Photocatalysts

The surface structure, particle morphology, and crystallite sizes of the photocatalysts before and after doping were investigated by SEM and TEM. SEM images of various photocatalyst powders are presented in Fig. 3a. Undoped AC/TiO2 exhibited smooth surfaces with a TiO2-particle-like morphology with irregular spherical shapes. Rough surfaces of AC/TiO2 spheres with obvious granular features were produced through N or Cu doping. In the case of the N–Cu-AC/TiO2 sample, the TiO2 particle sizes are quite uniform in a nearly spherical morphology and are well-distributed on the AC surface, as shown in the SEM images. Yi et al. [14] also reported that nonmetal and metal-codoped TiO2 present homogeneous morphologies, and this may be beneficial to enhanced catalytic efficiency. The TEM image (Fig. 3b) shows the presence of 10–40 nm powders, consistent with those calculated by XRD (Table 1). However, Cu cannot be observed in the TEM image, suggesting that Cu and N are doped into the TiO2 framework. XPS would confirm this.

FTIR Spectra

The FTIR spectra of various photocatalysts are shown in Fig. 4. All samples show similar FTIR spectra, indicating that the TiO2 structure did not change after doping with N and Cu. The absorption peak at 3445 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of surface hydroxyl groups—this could yield surface ⋅OH with a high oxidation capability [7]. The vibrations of the hydroxyl moiety were enhanced after AC/TiO2 doping (Fig. 4). Thus, doped AC/TiO2 may improve photocatalytic activity relative to undoped AC/TiO2. A band at around 1630 cm−1 is attributed to the bending vibration of the Ti-O bond. Compared with Cu-AC/TiO2, N-AC/TiO2 and N–Cu-AC/TiO2 display an additional peak at approximately 1080 cm−1 that can be assigned to the vibration of the N–Ti bond formed when N atoms are embedded in the TiO2 network [15].

UV-vis Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy

UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy permits the study of the optical properties and the TiO2 framework of the samples. Figure 5 (inset) shows the diffuse reflectance spectra of the prepared photocatalyst samples in the range 200–700 nm. The spectrum for pure AC/TiO2 shows an absorption edge of approximately 412 nm, whereas the N, Cu-monodoped samples show a red shift in the absorption edge and a strong absorption in the visible-light region. The absorption wavelengths of N, Cu-codoped AC/TiO2 increased to 450 nm. Application of the Kubelka–Munk [8] conversion can explain the red shift:

where α, hν, E g, and A are the absorption coefficient, photon energy, band-gap energy, and a constant, respectively. In accordance with the above equation, a modified plot of the Kubelka–Munk function versus the energy of the exciting light was used to determine the band gap of the samples. A band-gap value of 2.86 eV was obtained for AC/TiO2. According to data reported in literature, it is well-known that bulk anatase and rutile have the direct band-gap energy of 3.2 and 3.0 eV, respectively [3, 5]. This means that the radiation wavelength used for electron excitation of the titania should be smaller at about 387 nm (UV region). The band gap of TiO2-coated on AC samples decreased to 2.86 eV, indicating an influence of the AC support on the optical properties of TiO2 photocatalyst. Coromelci-Pastravanu et al. [7] also reported that the optical band gap of TiO2-coated mesoporous carbon samples decreases slightly comprised with pure TiO2. The carbon-based composites were found to be able to promote a rapid photoinduced charge separation and a slow charge recombination, by accepting photogenerated electrons from the photocatalytic TiO2 nanoparticles. After N doping, the band gap of TiO2 decreased to 2.81 eV and the band gap of Cu-AC/TiO2 was about 2.61 eV. Meanwhile, significant narrowing of the band gap to approximately 2.47 eV was observed after N, Cu codoping. This significant band-gap reduction is associated with charge-transfer, corresponding to the electronic excitation from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). Reduction in the band gaps correspondingly reduced the energy required for electron transition from the VB to the CB, thus shifting the optical absorption to a lower energy. This large decrease in band gap for the codoped catalyst may be attributed to the formation of mixed energy levels between the VB and CB. Thus, Cu and N doping promotes the visible absorption of the catalyst and plays a significant role in enhancing the photocatalytic activity of the catalysts.

XPS Characterization

XPS analysis of different photocatalysts was performed to examine the chemical states of each element (shown in Fig. 6). From the XPS spectra, all samples display peaks at about 458 and 464 eV, and these can be assigned to the Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2 of Ti4+ states, respectively, in the Ti2p core level [10]. Thus, the Ti is found as Ti4+ in the samples and this was not significantly affected by the incorporation of Cu and N. When investigating the Cu2p core level of Cu-AC/TiO2 and N–Cu-AC/TiO2, Cu was found to be present only in the oxidation state of Cu(II), with corresponding peaks at 932.8 (Cu-AC) and 933.2 (N–Cu-AC) [9]. This finding signifies that Cu is incorporated into the TiO2 lattice, in agreement with the XRD results. The peak at approximately 400 eV can be attributed to the interstitial N atoms in N–O bonds or Ti–(N–O) bonds in the case of N-AC/TiO2 and Cu–N-AC/TiO2, indicating that some nitrogen groups are adsorbed on the TiO2 as the interstitial N-doping [19]. An isolated level is formed above the VB because of the Cu-3d orbital in the case of Cu-doped AC/TiO2 [10], and this decreased the energy required for electronic excitation from the VB to CB, in accordance with the UV-vis results. Lin et al. [2] also reported that Cu doping makes the absorption edge of TiO2 red shift because of the transition of the excited 3d electrons from the Cu2+ ions to the CB of TiO2.

PL Spectra

The ⋅OH radicals in the reaction systems were detected by PL (Fig. 7). The radicals were generated on the four samples after illumination. The formation rate of the OH radicals on the AC/TiO2 powders increased after Cu, N doping on TiO2, and the generation rate of the ⋅OH radicals on the N–Cu-AC/TiO2 surface was higher than that of the other photocatalysts. A previous study reported that ⋅OH is the major reactive species for photocatalytic oxidation [33]. Sin et al. [34] also found that ⋅OH was the main active species during the Eu/ZnO degradation of phenol. The production rate of ⋅OH follows the order N–Cu-AC/TiO2 > Cu-AC/TiO2 > N-AC/TiO2 > AC/TiO2.

Photocatalytic Activity of Photocatalysts

The photocatalytic activity of these photocatalysts was evaluated by degradation of HCHO, as shown in Fig. 8. Under identical experimental conditions, N–Cu-AC/TiO2 showed much higher activities (94.38 % degradation efficiency) than those of pure AC/TiO2 (31.4 % degradation efficiency), N-AC/TiO2 (59.9 % degradation efficiency), and Cu-AC/TiO2 (83.6 % degradation efficiency), while the removing efficiency of HCHO without photocatalyst under irradiation and with N–Cu-AC/TiO2 in the dark for 150 min was about 2.74 and 8.67 %, respectively. First, the photocatalytic activity of the products corresponds to the generation rate of the ⋅OH radicals. Photocatalysis of HCHO in the presence of radical scavengers reduced reaction efficiency from 94.38 to 49.89 %, indicating that the hydroxyl radical initiated degradation is the dominant route over degradation by reactive electron-hole pairs on the catalyst surface and photolytic cleavage. The anatase/rutile ratio is an important factor in determining the photocatalytic activity of the samples through the formation of ⋅OH. The ratio of anatase/rutile (54/47) in Cu-AC/TiO2 is greater than that of pure AC/TiO2 (47/53). This resulted in more ⋅OH on the Cu-AC/TiO2 surface under irradiation. In N, Cu-codoped AC/TiO2, the ratio of anatase/rutile increased to 57/43, which led to the highest ⋅OH formation rate of the reaction systems studied. Commonly, the composite of two phases of the same semiconductor is beneficial for reducing the combination of photogenerated electrons and holes [1], thereby enhancing the ⋅OH formation rate. In N-AC/TiO2, the formation rate of ⋅OH decreased with the increase in anatase/rutile ratio to 62/38, implying that the optimal anatase to rutile ratio is likely approximately 57/43.

The most important factor for the enhancement of photocatalytic activity of doped AC/TiO2 is that Cu substitution of the partial Ti leads to an isolated energy band formation between the VB and CB in the band structure of TiO2. The formation of ⋅OH is attributed to the transition of electrons between the VB and CB. When doped with Cu, a two-step optical transition will occur because of the formation of the newly isolated energy band and the decrease in band-gap energy between the VB and the CB of TiO2, as shown in Fig. 5. This increased the optical response of Cu-doped AC/TiO2. In N-AC/TiO2, the Ti–N linkage may lead to formation of an N1s peak because of substitutional N doping in the TiO2 lattice [23]. Doping of N into TiO2 forms a new state on N1s, just above the VB, leading to strong absorption of visible light and enhancement in the separation efficiency of the photoinduced electrons and holes. The significant enhancement of photocatalytic activity of N, Cu-codoped AC/TiO2 in this study can be attributed to the synergistic effect of N, Cu codoping. Doping of the TiO2 lattice with Cu can lead to O vacancy production, which in turn facilitates N doping. Both Cu and N doped on TiO2 decreases the electronic transition energy and improve the photocatalytic activity of N–Cu-AC/TiO2.

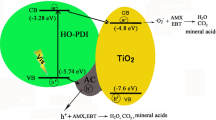

Mechanism of N, Cu-Codoped AC/TiO2

Figure 9 illustrates the band structures of the N, Cu-codoped AC/TiO2 materials. Possible mechanisms responsible for the observed improvement in photocatalytic activity of the new material under visible-light irradiation are proposed. When nitrogen is incorporated into the TiO2 lattice, the N2p states are positioned above the TiO2 CB, which increases the CB energy by 0.46 eV [35]. TiO2 band-gap narrowing also takes place, as shown in procedure 1 and compared with 1* in Fig. 9. Thus, the response light of N-AC/TiO2 is increased to 425 nm compared with 415 nm for pure AC/TiO2 (Fig. 5). For the Cu co-modified N-AC/TiO2, the light response increased to 465 nm (Fig. 5) because the band energy of TiO2 decreased to 2.47 eV (Table 1). In N–Cu-AC/TiO2, the Cu d-states lie deep in the band gap that lies below the CB of TiO2 [10]. In the case of visible-light irradiation, TiO2 can be excited at a wavelength <465 nm (procedure 1). Thereafter, the excited electron may be transferred from the TiO2 CB to the Cu CB (procedure 2), thereby improving the charge separation and allowing oxidation/reduction processes to occur on the TiO2 VB/Cu CB. Yang et al. [36] also reported that Cu species have smaller band gaps and higher work functions than does bare TiO2, so the electron can transfer from the CB of TiO2 to a metallic copper ion. The excited electrons can be further scavenged by surface-adsorbed H2O on the TiO2 to generate ⋅OH and other active species. Moreover, the electron from the Cu VB may also be transferred to the TiO2 VB (procedure 3), creating a hole in the Cu VB. The additional charge separation significantly improves the photocatalytic performance. In addition, the mixed phases of anatase and rutile in TiO2 can inhibit the electron-hole recombination of TiO2 and thus enhance the photocatalytic ability [37, 38]. Thus, the photocatalytic performance enhancement of TiO2 may be attributed to the synergistic effect of Cu and N co-implantation, which resulted in a change in the electronic and band-gap structures.

Reusability of the Catalyst

The stability and recyclability of a photocatalyst are important for its potential application. To evaluate the stability of the N–Cu-AC/TiO2 catalysts, the nanoparticles were collected after the photocatalytic reaction, and then the nanoparticles were put in ethanol solution with ultrasonic treatment for 2 h, dried at 120 °C for 4 h. The photocatalytic test was repeated up to seven times while keeping all other parameters constant. Figure 10 shows that, after the seven recycling experiments, the N–Cu-AC/TiO2 particles retained their high photocatalytic activity, and 80.2 % of the HCHO was degraded. This result indicated that the N, Cu-codoped AC/TiO2 prepared in the present study had good photocatalytic stability and allowed for possible repeat utilization.

Conclusion

A novel and simple technique for incorporating N and Cu on TiO2 nanoparticles loaded on AC was presented. The nanoscale TiO2 showed anatase and rutile phases with a particle size of 18 nm, an appropriate proportion in codoped AC/TiO2, and a specific surface area of 548 m2/g. Nitrogen and Cu may occupy the internal TiO2 crystal framework, replacing some Ti4+ and O2−, respectively, and extending the band-gap excitation to the visible region. The obtained N–Cu-AC/TiO2 shows a distinctive absorption band in the visible region and presents the lowest band-gap value among all of the samples studied. The N–Cu-AC/TiO2 photocatalyst exhibited good photocatalytic activity for the degradation of HCHO under visible-light irradiation. The incorporation of Cu and N may decrease the required energy for electronic transitions, thereby improving the photocatalytic activity. Furthermore, the produced photocatalyst can be easily recycled and exhibits enhanced stability. Therefore, using N, Cu-doped AC/TiO2 for pollutant photodegradation is a practical method for purifying water under visible light.

References

Yu JG, Wang WG, Cheng B, Huang BB, Zhang XY (2009) Preparation and photocatalytic activity of multi-modally macro/mesoporous titania. Res Chem Intermediat 35:653–665

Lin CJ, Yang WT (2014) Ordered mesostructured Cu-doped TiO2 spheres as active visible-light-driven photocatalysts for degradation of paracetamol. Chem Eng J 237:131–137

Yang YQ, Zhang GK, Xu W (2012) Facile synthesis and photocatalytic properties of Ag-AgCl-TiO2/rectorite composite. J Colloid Interf Sci 376:217–223

Ya J, Yang NN, Hu FJ, Liu ZF, Lei E (2015) Preparation and activity evaluation of TiO2/Cu-TiO2 composite catalysts. J Sol–gel Sci Techn 73:322–331

Liu X, Gao S, Xu H, Lou Z, Wang W, Huang B, Dai Y (2013) Green synthetic approach for Ti3+ self-doped TiO2−x nanoparticles with efficient visible light photocatalytic activity. Nanoscale 5:1870–1875

Yoneyama H (1996) Effects of adsorbents used as supports for titanium dioxide loading on photocatalytic degradation of propyzamide. Environ Sci Technol 30:1275–1281

Coromelci-Pastravanu C, Ignat M, Popovici E, Harabagiu V (2014) TiO2-coated mesoporous carbon: conventional vs. microwave-annealing process. J Hazard Mater 278:382–390

Nagaveni K, Hegde MS, Madras G (2004) Structure and photocatalytic activity of Ti1-xMxO2±σ (M = W, V, Ce, Zr, Fe and Cu) synthesized by solution combustion method. J Phys Chem B 108:20204–20212

Xu Y, Li J, Yao LF, Li LH, Yang P, Huang N (2015) Preparation and characterization of Cu-doped TiO2 thin films and effects on platelet adhesion. Surf Coat Tech 261:436–441

Choudhury B, Dey M, Choudhury A (2014) Shallow and deep trap emission and luminescence quenching of TiO2 nanoparticles on Cu doping. Appl Nanosci 4:499–506

Sahu M, Biswas P (2011) Single-step processing of copper-doped titania nanomaterials in a flame aerosol reactor. Nanoscale Res Lett 6:1–14

Wu HB, Zhang XY, Geng ZH, Yin Y, Hang RQ, Huang XB, Yao XH, Tang B (2014) Preparation, antibacterial effects and corrosion resistant of porous Cu-TiO2 coatings. Appl Surf Sci 308:43–49

Wang S, Meng KK, Zhao L, Jiang Q, Lian JS (2014) Superhydrophilic Cu-doped TiO2 thin film for solar-driven photocatalysis. Ceram Int 40:5107–5010

Yi WT, Yan CY, Yan P, Li FQ (2014) A new perspective for effect of S and Cu on the photocatalytic activity of S, Cu-codoped nano-TiO2 under visible light irradiation. J Sol–gel Sci Techn 69:386–396

Chen CJ, Liao CH, Hsu KC, Wu YT (2011) P-N junction mechanism on improved NiO/TiO2 photocatalyst. Catal Commun 12:1307–1310

Zhang H, Du G, Lu W, Cheng L, Zhu X, Jiao Z (2012) Porous TiO2 hollow nanospheres: synthesis, characterization and enhanced photocatalytic properties. Cryst Eng Commun 14:3793–3801

Khalilzadeh A, Fatemi S (2014) Modification of nano-TiO2 by doping with nitrogen and fluorine and study acetaldehyde removal under visible light irradiation. Clean Technol Envir 16:629–636

Huang BS, Wey MY (2014) Characterization of N-doped TiO2 nanoparticles supported on SrTiO3 via a sol-gel process. J Nanopart Res 16:1–8

Ai HY, Shi JW, Chen JW, Fu ML (2014) The preparation of nitrogen-doped TiO2 nanocrystals with exposed facets and their visible-light photocatalytic performances. Chinese Sci Bull 59:2199–2207

Zhang K, Wang XD, Guo XL, He TO, Feng YM (2014) Preparation of highly visible light active Fe-N co-doped mesoporous TiO2 photocatalyst by fast sol-gel method. J Nanopart Res 16:1–9

Jiang HQ, Wang QF, Zang SY, Li JS, Wang XF (2014) Hydrothermal synthesis of high-efficiency Pr, N, P-tridoped TiO2 from TiCl4 hydrolysis and mechanism of its enhanced photoactivity. J Alloy Compd 600:34–42

Jia LC, Wu CC, Han S, Yao N, Li YY, Li ZB, Chi B, Pu J, Jian L (2011) Theoretical study on the electronic and optical properties of (N, Fe)-codoped anatase TiO2 photocatalyst. J Alloy Compd 509:6067–6071

Li YX, Jiang Y, Peng SQ, Jiang FY (2010) Nitrogen-doped TiO2 modified with NH4F for efficient photocatalytic degradation of formaldehyde under blue light-emitting diodes. J Hazard Mater 182:90–96

Li Y, Kuang XY, Li HL, Mao AJ, Tang LJ (2008) Investigation of the EPR and local defect structures for (FeO6)9− and (MnO6)10− clusters in TiO2 crystal at different temperature. Chem Phys Lett 461:160–163

Mothi KM, Soumya G, Salim AH, Sugunan S (2014) Visible light active Ag, N co-doped titania in the photo-oxidation of some 9-(N, N-dimethylaminomethyl) anthracene systems. J Sol–gel Sci Techn 71:549–556

Xiao XM, Tian F, Yan YJ, Wu ZS (2014) Adsorption behavior of pyrene from onto coal-based activated carbons prepared by microwave activation. J Shihezi Univ 32:485–490

Xiao XM, Tian F, Yan YJ, Wu ZL, Wu ZS, Cravotto G (2015) Adsorption behavior of phenanthrene onto coal-based activated carbon prepared by microwave activation. Korean J Chem Eng 32:1129–1136

Zhang ZH, Yu FY, Huang LR, Jiatieli J, Li YY, Song LJ, Yu N, Dionysiou DD (2014) Confirmation of hydroxyl radicals (⋅OH) generated in the presence of TiO2 supported on AC under microwave irradiation. J Hazard Mater 278:152–157

Wang Y, Yu JG, Xiao W, Li Q (2014) Microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of graphene based Au-TiO2 photocatalysts for efficient visible-light hydrogen production. J Mater Chem A 2:3847–3855

Tian F, Wu ZS, Yan YJ, Ge XY, Tong YB (2015) Photodegradation of formaldehyde by activated carbon loading TiO2 synthesized via microwave irradiation. Korean J Chem Eng 32:1333–1339

Tian F, Wu ZS, Chen QY, Yan YJ, Cravotto G, Wu ZL (2015) Microwave-induced crystallization of AC/TiO2 for improving the performance of rhodamine B dye degradation. Appl Surf Sci 351:104–112

Zhu YY, Ling Q, Liu YY, Wang H, Zhu YF (2016) Photocatalytic performance of BiPO4 nanorods adjusted via defects. Appl Catal B Environ 187:204–211

Girish Kumar S, Koteswara Rao KSR (2014) Polymorphic phase transition among the titania crystal structures using a solution-based approach: from precursor chemistry to nucleation process. Nanoscale 6:11574–11632

Sin JC, Lam SM, Satoshi I, Lee KT, Mohamed A (2014) Sunlight photocatalytic activity enhancement and mechanism of novel europium-doped ZnO hierarchical micro/nanospheres for degradation of phenol. Appl Catal B Environ 148–149:258–268

Xu JC, Chen C, Xiao XH, Liao L, Miao L, Wu W, Mei F, Stepanov AL, Cai GX, Liu Y, Dai ZG, Ren F, Jiang CZ, Liu JR (2014) Synergistic effect of V/N codoping by ion implantation on the electronic and optical properties of TiO2. J Appl Phys 115:1–6

Yang XJ, Wang S, Sun HM, Wang XB, Lian JS (2015) Preparation and photocatalytic performance of Cu-doped TiO2 nanoparticles. T Nonferr Metal Soc 25:504–509

Yang DJ, Liu HW, Zheng ZF, Yuan Y, Zhao JC, Waclawik ER, Ke XB, Zhu HY (2009) An efficient photocatalyst structure: TiO2(B) nanofiberswith a shell of anatase nanocrystals. J Am Chem Soc 131:17885–17893

Hurum DC, Agrios AG, Gray KA, Rajh T, Thurnauer MC (2003) Explaining the enhanced photocatalytic activity of Degussa P25 mixed-phase TiO2 using EPR. J Phys Chem B 107:4545–4549

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51262025) and the International Scientific and Technological Cooperation Project of Xinjiang Bingtuan (2013BC002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

FT and ZSW provided the idea and drafted the manuscript. FT, BCY, and XQC designed and carried out the experiment. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Master FT is a student of Shihezi University. His major research area is in material science.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, F., Wu, Z., Yan, Y. et al. Synthesis of Visible-Light-Responsive Cu and N-Codoped AC/TiO2 Photocatalyst Through Microwave Irradiation. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 292 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1503-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1503-9