Abstract

This paper reports a novel implanting micromachining technology. By using this method, for the first time, we could implant nano-scale materials into milli-scale metal substrates at room temperature. Ni-based flexible carbon nanotube (CNT) field emitters were fabricated by the novel micromachining method. By embedding CNT roots into Ni foil using polymer matrix as transfer media, effective direct contact between Ni and CNTs was achieved. As a result, our novel emitter shows relatively good field emission properties such as low turn-on field and good stability. Moreover, the emitter was highly flexible with preservation of the field emission properties. The excellent field emission characteristics attributed to the direct contact and the strong interactions between CNTs and the substrate. To check the practical application of the novel emitter, a simple X-ray imaging system was set up by modifying a traditional tube. The gray shadow that appears on the sensitive film after being exposed to the radiation confirms the successful generation of X-ray.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) exhibit excellent field emission characteristics due to their inherent small tip radius and high aspect ratio combined with robust chemical and mechanical stabilities [1]. Flexible electronic devices have recently attracted great attention for their diverse applications such as bendable sensors [2], flexible displays [3], and X-ray radiotherapy [4]. There are many advantages of flexible emitters that show reliable field emission performance under various bending conditions, allowing emitters to be made in any geometry or shape in field emission applications. Although, high-performance field emitters with a stable emission current of 1 A (current density of 4 A/cm2) have already been reported [5, 6]. It is believed that, as the heart of field emission electronic devices, the carbon nanotube field emitters have not reached their full potential and there are still lots of challenges in this field [7].

In recent years, several groups have been engaged in fabricating CNT emitters on polymeric substrates for flexibility purposes by using electrophoretic method [8], direct growth [9], transfer [10, 11], and wet coating [3]. However, there are several problems that arise from the polymer substrate hindering its practical application. For weak mechanical adhesion between CNTs and the polymer substrate, the structure and morphology can be easily damaged under complex curving conditions, resulting in a catastrophic vacuum breakdown or arcing during device operation [12]. Low thermal conductivity and low thermal degeneration temperature of the polymer substrate can lead to joule heating of the interface [13], thereby damaging the emitter interface and resulting in the increase of the turn-on field over extended periods [14].

Metal substrates, with good mechanical properties and high thermal conductivity, seem to be the most promising substrate for low-cost, flexible, and arbitrary-shaped emitters. However, weak adhesion between CNTs and the metal substrates is the most crucial limitation blocking their commercial application for flexible emitters [15]. There are also technological difficulties in preparing disentangled CNTs and dispersing them homogeneously onto the metal substrates.

We have used an implanting micromachining method to solve these problems. With this technique, polymer is firstly used as transfer media, for CNTs could be homogeneously disentangled into the polyimide matrix. By selective wet etching method and electroplating technology, polyimide works as a sacrificial layer, and CNTs were transferred into Ni foil. This is a relatively simple method that can be easily realized at room temperature. The fabricated Ni foil was highly flexible with preservation of the field emission properties. To check the application of this novel flexible foil, an X-ray imaging experiment was performed. A simple diode X-ray source assembly was achieved based on a traditional X-ray tube. By comparing the images that were obtained from the X-ray system at different emission currents, we confirm the generation of X-rays using our cathode. It is believed that this novel method must be helpful for CNT cathode wide industrialized application.

Methods

Apparatus

A mechanical ball-milling machine (QM-QX04 of Nanjing University Instrument Plant, China) was used for mixing CNT and polyimide (PI). The morphologies of the fabricated emitters were characterized using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM; Zeiss Ultra 55, Germany). The Raman spectrum of the flexible emitters was obtained using a Raman microscope (Ram, Bruker Optics Senterra R200, USA) with ×10 and ×100 objectives at a laser wavelength of 532 nm. Spectrum acquisitions were done with a power of 1 mW with integration times of 10–60 s depending on the sample examined.

The field emission characteristics of the samples were measured in a vacuum chamber with a parallel diode-type configuration at a pressure of 1 × 10−6 Torr. A mica sheet with a round hole (Ø = 3 mm) was used as a spacer. A DC voltage was applied by a high-voltage power supply (HBGY HB-2502-100AC, China) across the cathode and the anode with a distance of 150 μm. The current was measured and saved by a digital multi-meter (Agilent 34401A, USA). In order to protect high-voltage power supply from high-voltage arcing breakdown, a current-limiting resistor (2 MΩ) was used.

Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNT) with the purity more than 95 % (diameter 30–50 nm, length 5–15 μm) were bought from Timesnano Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). PI (absolute viscosity 1100–1200 mPa s) was bought from POME Sci-tech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Cathode Fabrication

The CNT composite paste is composed of CNT and PI. To maintain the intrinsic properties of CNTs, no surfactant was added to the paste. And the homogeneous CNT-PI paste was achieved using just the ball-milling apparatus. By selective wet etching method, sputtering, and electroplating technology, PI worked as a sacrificial layer, and CNTs were transferred into Ni film. The preparation process is presented as follows (Fig. 1):

-

(a)

The homogeneous CNT-PI paste was spun on the glass wafer, the CNT/PI film was formed by baking at 90 °C for 2 h, and then, the film was polished.

-

(b)

Selective chemical etching (the wafer was immersed in the etchant (composed of sodium hydroxide, ethyl alcohol, and sodium hydrogen phosphate)) was carried out, a thin layer of PI of micron level was etched away from the PI/CNT film, and a flat surface with protruding tips of CNTs was achieved.

-

(c)

The Ni conducting layer of 50 nm was sputtered on the above flat surface and covered the protruding tips of CNTs.

-

(d)

Photoresist of 10 μm was spun on the Ni layer, and lithography was performed to develop the pattern area for the Ni foil emitter.

-

(e)

Then, Ni foil (the reasons for choosing Ni as the basement are its resistance to corrosion and favorable mechanical properties) was fabricated by electroplating on the Ni conducting layer.

-

(f)

Selective chemical etching was carried out to remove the remaining PI and photoresist. The wafer was immersed in the etchant (composed of sodium hydroxide, ethyl alcohol, and sodium hydrogen phosphate), sonicated for 30 min, and flushed by deionized water, and then, the Ni foil emitter with free-standing CNTs on its surface was achieved.

All the above steps were carried out at room temperature. A contaminant-free method, rolling by a soft rubber roller was used for posttreatment. And SEM was used to analyze the surface morphology of the Ni foil.

Results and Discussion

Due to their small tip radius and high aspect ratio, CNTs have a highly entangled structure, which needs to be dispersed, preferably up to a single nanotube level, for practical applications. Ball-milling process was employed to improve the CNT dispersion, and the CNT aggregate (composed of many CNTs) size distribution was investigated by a laser particle size analyzer. According to the particle size evolution in Fig. 2a, the particle size decreased and the length distribution narrowed down with increasing milling time. The aggregate particle size decreased from over 1200 nm to approx 804 nm in the first 1-h milling, and then, the rate of aggregate size reduction slowed down. Average sizes of about 699, 616, and 533 nm could be achieved after milling for 4, 8, and 16 h, respectively.

During the ball-milling process, large CNT aggregate died down, and CNTs turned into conglomeration which was closed to the granules and sheets because of the friction of rolling between the balls [16]. It is believed that the ball-milling process not only decreased the aggregate size but also changed some CNTs into amorphous carbon. The CNT structure changes made by the ball-milling process were investigated by microprobe Raman technique. As shown in Fig. 2b, there are two sharp peaks at 1350 cm−1 (D bond) and 1580 cm−1 (G bond) representing typical characteristics of amorphous and graphite carbons, respectively. The D bond at 1350 cm−1 is generally attributed to defects in the curved graphite sheet or other impurities, while the G bond at 1580 cm−1 is corresponding to the opposite direction movement of two neighboring carbon atoms in a graphitic sheet, and it indicates the presence of crystalline graphitic carbon in CNTs [17].

To study their structure changes in detail, relative value (R-value, I D/I G) is shown in Fig. 3b. It is generally agreed that the R-value provides a useful index for comparing the crystallite sizes (more specifically, peak area of the Lorentzian functions) of various carbon materials. The R-value of the samples treated for 0, 1, 4, 8, and 16 h is 0.721, 0.735, 0.752, 0.802, and 0.849, respectively. It reveals that the R-value of the D bond increases against the milling time, which indicates a small increase in defect density. From the results above, we can see that the CNT dispersion was significantly improved by the ball-milling process; however, shortened CNTs with more structural defects were obtained.

By the ball-milling process, CNTs dispersed homogeneously in PI, and a smooth CNT-PI composite film was achieved on the glass wafer (Fig. 3a). We can see that CNTs were uniformly embedded in the cross section (Fig. 3b), which indicated the homo-dispersion of CNTs in the horizontal direction. Similarly, in Fig. 3c, the CNTs evenly and randomly dispersed in the PI film in a vertical direction. It can be deduced that PI can offer good wetting property for CNTs and homogeneous dispersion of CNTs in PI lays a foundation for the mass production of CNT-modified electrode using micromachining.

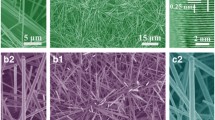

Selective wet etching played an important role in this implanting method. The CNT/PI film surface morphology after etching for 60, 120, 240, and 480 s is shown in Fig. 4a–d. With the etching time increased, PI was etched away, and more and longer CNTs exposed from the surface (the “root” means of the CNTs exposed from the PI surface after wet etching). As a result, the surface morphology of the fabricated emitter differed from one another (as shown in Fig. 4e–h). For the samples etched for 60 and 120 s, only a small amount of nanotubes exposed from the surface after the wet etching, resulting in a few of nanotubes being implanted into the Ni foil. As the short “root” buried in the Ni foil could hardly bear the strain of the whole tube weight, it was easily dropped out during the fabrication, resulting in a trail left on the foil (as shown in Fig. 4e, f). For the samples etched for too much time, large amounts of nanotubes could be achieved. However, the long “root” was easily twisted and buried in the Ni foil, resulting in short CNTs exposed on the foil (as shown in Fig. 4h). As we know, the vertical alignment and uniform distribution of the CNTs in the Ni substrate actively contributed to stable electron emission when an electric field is applied, and we carefully controlled the distribution and height of CNTs exposed on the foil by the wet etching process.

Figure 5 shows the two sharp peaks at 1350 cm−1 (D bond) and 1580 cm−1 (G bond) representing typical characteristics of amorphous and graphite carbons, respectively. The appearance of those two peaks in the emitter surface indicated that the CNTs were successfully transferred onto the Ni substrate by the implanting process. The D bond at approximately 1350 cm−1 is generally attributed to defects in the curved graphite sheet or other impurities, while the G bond at approximately 1580 cm−1 is corresponding to the opposite direction movement of two neighboring carbon atoms in a graphitic sheet, and it indicates the presence of crystalline graphitic carbon in CNTs. It shows that the I D/I G ratio of pristine CNT is 0.721 and it increases to 0.847 after the preparation process, indicating decreased crystallinity and improved defects in the CNTs. The main reason for this phenomenon is that the ball-milling process was used to disperse CNTs into the transfer media (PI). The ball-milling process not only decreased the CNT aggregate size but also changed some CNTs into amorphous carbon. Also from the results, we can see that the I D/I G ratio (0.847) of the CNTs on the emitter keeps almost the same as the I D/I G ratio (0.849) of the CNTs after the ball-milling process. It is believed that the chemical wet etching process brings negligible structural changes to the CNTs.

Figure 6a shows the optical image of the glass wafer after processing with Ni foil emitters on it. By using this method, we can get 19 pieces of emitters on each 3-in. wafer. It takes only six procedures to fabricate each wafer, as all the procedures were carried out at room temperature, and the novel fabrication process could be more compatible with other IC procedures. By choosing Ni as the substrate, the emitter showed good mechanical properties for planar supporting and large amplitude bending, and it could even be twisted and rolled up (Fig. 6b). As the CNT roots were firmly embedded in the substrate, strong adhesion could be achieved, avoiding the CNT detachment during the fierce field emission process. The foil surface morphology was inspected by SEM. From the images (Fig. 6c–f), we can see that the Ni substrate is totally covered by the dense CNTs. The CNT roots are firmly embedded in the substrate, and no contamination is induced. In addition, the distribution and height of CNTs were well controlled by the micromachining process. The vertical alignment and uniform distribution of the CNTs in the Ni substrate were actively contributed to stable electron emission when an electric field was applied.

Field emission of CNT arrays on the Ni foil emitter was carried out in a vacuum chamber. An aging process was carried out with an applied voltage of 550 V for 12 h before the test. During the aging process, arcing occurred occasionally. Since CNTs of greater heights contribute to higher field emission current, thermal runaway is more serious at longer CNTs. As a result, longer CNTs became short and vertically standing CNTs with more uniform heights remained on the Ni substrate after the aging process. The emission current vs. applied electric voltage were repeatedly measured (in Fig. 7), and the I-V curves remained almost constant at the repeated field emission tests. The emission current increases monotonically with the applied field. The turn-on field, which is defined as an electric field required to get an emission current of 10 μA, was 1.64 V/μm. We simply consider the area of the hole on the mica spacer as the field emission area, as the mica sheet was closely attached to the field emitter. The area S = π*(Ø/2)2 = 0.071 cm2. With the applied field of 3.13 V/μm, the field emission current of 0.57 mA and the current density of 8.03 mA/cm2 was achieved. In Fig. 7, the emission current curve seems to show a “linear” relation with the applied field from 400 to 450 V. The phenomenon was caused by the current-limiting resistor which shared the voltage of the field emitter in the circuit. The corresponding Fowler-Nordheim (F-N) plot for the flexible emitter is shown in the inset of Fig. 7. All dots on the curve fit a single straight line well, which implies that the field emission process follows the F-N mechanism.

Before continuous emission measurement, an aging process was carried out for 12 h with driving condition of a higher applied voltage at 550 V. And the short-term stability of the CNT field emitter was evaluated by monitoring emission current under constant DC operation for 40 h.

As shown in Fig. 8, with the applied fields of 2.05, 2.30, 2.66, and 1.43 V/μm, emission currents of 58.9, 104.4, 204.2, and 310.5 μA could be achieved, they remained almost constant during the 40-h continuous measurement, and the fluctuation widths of the emission current for 40 h were all in ±5 %. One thing to note here is that a few arcing events occurred when the emission current reached higher than 300 μA; however, the emitter could withstand the arcing and the emission current remained constant with time. The stable emission performance was primarily due to the firm, direct bonding between CNTs and Ni substrate, which greatly reduces the contact resistance between CNTs and substrate and the damnification of CNTs escaping from the emitter surface.

For comparison, we have included some of the best values obtained from a few past CNT flexible emitters (Table 1). It is evident from our data that the flexible devices exhibited excellent field emission. Although the turn-on field for our emitter is relatively high, the definitions of the turn-on field in the references are different. The maximum emission current obtained from our emitter was 0.57 mA (8.03 mA/cm2) with the applied field of 3.13 V/μm, which was seldom reported in the past MWNT flexible emitters.

The flexible field emission properties of the Ni foil emitter were measured using a sandwich structure, two pieces of ITO-PET (indium tin oxide-coated polyethylene terephthalate plastic) films acting as the cathode and the anode, and a piece of PI film with a thickness of 150 μm as a spacer, as described in the inset of Fig. 9. The ITO-PET film was used for the cathode substrate, and the emitter was adhered onto the ITO-PET film by using conductive adhesive tape.

The foil emitter was highly flexible without incurring a reduction in field emission properties under severe bending conditions. Figure 9 shows the relationship of emission current with the applied voltage and the corresponding F-N characteristics of the Ni foil emitter with respect to the bending angle, respectively. In the flat sample configuration, an emission current density of 8.03 mA/cm2 at an electric field of 3.13 V/μm was measured. With the same electric field, the emission currents of 7.93, 8.03, 8.10, and 7.96 mA/cm2 were achieved at the bending angles of 15°, 30°, 45°, and 60°, respectively. And also, the release of the sample resulted in the return of the emission current density to its original value. The slopes of the linear F-N regions were also quite similar, regardless of the bending angle. This stable flexibility in the field emission of the sample may have originated from the direct contact as well as the strong interactions between CNTs and the Ni substrate. Consequently, the fabricated Ni foil emitter exhibits very stable field emission properties, which are useful for the realization of miniature X-ray tubes that require high-voltage operation.

To check the practical application of the novel emitter, a simple X-ray imaging system was set up. The electrode structure for X-ray generation was modified based on a traditional hot X-ray tube. The Ni foil emitter was used as the cathode with bending form as shown in Fig. 10a. The compact X-ray measurement system was set up, with a simple diode-type (i.e., consisting of a cathode and an anode) configuration of an electron source and a tungsten-embedded copper anode. The distance between cathode and the copper anode was maintained at 1.5 mm. The proof of X-ray creation was done by using an X-ray-sensitive film. This film was commercially available (Kodak Insight, 31 × 41 mm2) and widely used in dental diagnostics as standard X-ray analog film plates. The detection was done by placing the film in front of the anode inside the vacuum chamber.

The X-ray source assembly was successfully operated at 2.5, 2.8, 3.7, 4.1, and 4.2 kV, with an extraction current from the cathode of 47, 102, 213, 307, and 423 μA, respectively. As the tungsten anode is surrounded by a copper “hat,” the electric field between cathode and anode is complex. And with the help of the “anode hat,” the electric field around the emitter is significantly improved. As a result, the system can be operated under a relatively low voltage. A round lead aperture (copper film with a pin hole (Φ = 3 mm)) was put in front of the photosensitive plate in order to create a defined pattern when exposed to radiation, and the shadow of the aperture thus unequivocally confirms the X-ray emission. The photosensitive plates placed in front of the source were exposed to the radiation under emission current for 10 min to compensate for the X-ray energy loss. The above exposed plates were then developed in accordance with the photographic processing. The photograph of the developed copy can be seen in Fig. 10b–g. The gray round shadow on this copy confirms the generation of X-rays. Furthermore, the gray round shape becomes clearer with the increase of the emission current.

Then, a Ni badge with a thickness of 100 μm and diameter of 3 mm was placed between the pin hole and the sensitive plate. The sensitive plate and the badge were exposed to the radiation under an applied voltage of 2.7 kV and emission current of 81 μA for 30 min to compensate for the X-ray energy loss. Figure 11 shows the X-ray transmission image of the Ni badge, and a fuzzy image was obtained at a relatively low applied voltage.

These results above demonstrate that X-rays are generated in our setup. The Ni foil CNT field emitter with a high and stable emission current proved to be available for X-ray generation without any focusing and accelerating installation.

Conclusions

In this study, we have introduced a novel method to fabricate Ni-based flexible cathode using micromachining at room temperature. Polymer was used as transfer media, and by using simple selective wet etching method and electroplating technology, CNTs were firmly embedded into the Ni substrate. The emitter showed good mechanical properties for planar supporting and large amplitude bending. Effective direct contact between CNTs and Ni substrate was achieved, which would be crucial for low contact resistance between them. Meanwhile, as the CNT roots were firmly buried into the Ni substrate, there would hardly be any detachment of CNTs from the substrate induced by weak adhesion. As a result, our novel emitter showed relatively good field emission properties such as low turn-on field (1.64 V/μm), high current density (8.03 mA/cm2 at an applied electric field of 3.13 V/μm), and good stability (40 h for 5 % fluctuation of emission current around 300 μA). The novel emitter also showed great potential used as an X-ray tube electron source. The round gray pattern that appears on the sensitive film after exposing to the radiation confirms the X-ray generation in a simple diode system without any focusing and accelerating installation. And the shade of the round pattern darks with the increase of the applied field. From those results, it is believed that this new method based on micromachining can be helpful for wide industry application of CNT-based cathode in an X-ray tube, yet further optimization in device configuration and cathode structure is required.

References

Fan SS, Chapline MG, Franklin NR, Tombler TW, Cassell AM, Dai HJ (1999) Self-oriented regular arrays of carbon nanotubes and their field emission properties. Science 283:512–514

Kanoun O, Muller C, Benchirouf A, Sanli A, Dinh TN, Al-Hamry A (2014) Flexible carbon nanotube films for high performance strain sensors. Sensors 14:10042–10071

Jung H, An SY, Jang DM, Kim JM, Park JY, Kim D (2012) A multi-wall carbon nanotube/polymethyl methacrylate composite for use in field emitters on flexible substrates. Carbon 50:987–993

Tan TT, Sim HS, Lau SP, Yang HY, Tanemura M, Tanaka J (2006) X-ray generation using carbon-nanofiber-based flexible field emitters. Appl Phys Lett 88:103–105

Calderon-Colon X, Geng HZ, Gao B, An L, Cao GH, Zhou O (2009) A carbon nanotube field emission cathode with high current density and long-term stability. Nanotechnology 20:325707–325712

Zhu W, Bower C, Zhou O, Kochanski G, Jin S (2010) Large current density from carbon nanotube field emitters. Appl Phys Lett 75:873–875

Saito Y (2010) Carbon nanotube and related field emitters: fundamentals and applications. Wiley

Zhang JH, Zang JB, Huang JJ, Wang YH, Xin GX (2014) Synthesis of an architectural electrode based on manganese oxide and carbon nanotubes for flexible supercapacitors. Mater Lett 126:24–27

Jeong HJ, Jeong HD, Kim HY, Kim JS, Jeong SY, Han JT (2011) All-carbon nanotube-based flexible field-emission devices: from cathode to anode. Adv Funct Mater 21:1526–1532

Jung YJ, Kar S, Talapatra S, Soldano C, Viswanathan G, Li XS (2006) Aligned carbon nanotube-polymer hybrid architectures for diverse flexible electronic applications. Nano Lett 6:413–418

Shin DH, Jung SI, Yun KN, Chen G, Song YH, Saito Y (2014) Field emission properties from flexible field emitters using carbon nanotube film. Appl Phys Lett 105:033110

Ha JM, Kim HJ, Raza HS, Cho SO (2013) Highly stable carbon nanotube field emitters on small metal tips against electrical arcing. Nanoscale Res Lett 8:355–363

Kumar A, Pushparaj VL, Kar S, Nalamasu O, Ajayan PM, Baskaran R (2006) Contact transfer of aligned carbon nanotube arrays onto conducting substrates. Appl Phys Lett 89:163120–163122

Kottler C, Longtin R, Giudice S, Jose-James R, Niedermann P, Neels A (2014) X-ray source downscaling enabled by combining microfabricated electrodes with carbon nanotube cold electron emitters. Microelectron Eng 122:13–19

Park JS, Kim JP, Noh YR, Jo KC, Lee SY, Choi HY (2010) X-ray images obtained from cold cathodes using carbon nanotubes coated with gallium-doped zinc oxide thin films. Thin Solid Films 519:1743–1748

Kim G, Jeong BW, Ihm J (2006) Deep levels in the band gap of the carbon nanotube with vacancy-related defects. Appl Phys Lett 88:193107

Wei G (2006) Emission property of carbon nanotube with defects. Appl Phys Lett 89:143111

Jo SH, Huang JY, Chen S, Xiong GY, Wang DZ, Ren ZF (2005) Field emission of carbon nanotubes grown on carbon cloth. J Vac Sci Technol B 23:2363–2368

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the colleagues of the National Key Laboratory of Nano/Micro Fabrication Technology. Thanks for their support and encouragement. The authors would like to appreciate the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51305265, No. 51205390) and the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (No. 20120073110061).

Authors’ contributions

Prof YW helped me with the field emission tests, and design the experiments with me. Prof GD gave me the idea of using field emitter for X ray generation. Both of them are my supervisors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

The Editors-in-Chief have retracted this article [1] because it significantly overlaps with a previously published article by the same authors [2].

The authors agree with this retraction.

[1] Sun, B., Wang, Y. & Ding, G. (2016) Flexible Field Emitter for X-ray Generation by Implanting CNTs into Nickel Foil Nanoscale Res Lett 11: 326. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1523-5

[2] B. Sun, Y. Wang, and G. Ding (2016) Fabrication of a Ni-matrix CNT flexible field emission electron source for X-ray generation by micromachining, Opt. Mater. Express 6, 2304-2312 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1364/OME.6.002304

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, B., Wang, Y. & Ding, G. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Flexible Field Emitter for X-ray Generation by Implanting CNTs into Nickel Foil. Nanoscale Res Lett 11, 326 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1523-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1523-5