Abstract

Ultrafast pump-probe and transient photoluminescence spectroscopy were used to investigate carrier dynamics in β-Ga2O3 nanowires converted to β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 under H2S between 400 to 600 °C. The β-Ga2O3 nanowires exhibited broad blue emission with a lifetime of 2.4 ns which was strongly suppressed after processing at 500–600 °C giving rise to red emission centered at 680 nm with a lifetime of 19 μs. Differential absorption spectroscopy reveals that state filling occurs in states located below the conduction band edge before sulfurization, but free carrier absorption is dominant in the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 nanowires processed at 500 to 600 °C for probing wavelengths >500 nm related to secondary excitation of the photo-generated carriers from the mid-gap states into the conduction band of Ga2S3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Metal oxide (MO) semiconductor nanowires (NWs) such as SnO2, In2O3, and Sn-doped In2O3, have been investigated extensively for the fabrication of nanoscale devices such as sensors and nanowire solar cells [1, 2]. With the incorporation of MO NWs in such devices that are subjected to various gasses such as NH3, H2S, or liquids containing S, Na2S requires an understanding of their effect on the electrical, optical, and structural properties of the MO NWs. In the past, we investigated the growth and properties of SnO2 [3], In2O3 [4], Sn-doped In2O3 [5], and β-Ga2O3 NWs and found that they exhibit photoluminescence at ≈ 2.5 eV due to oxygen vacancies and states residing energetically in the upper half of the energy band gap as shown by ultrafast absorption spectroscopy [6].

More recently, we showed that post growth processing of SnO2 and Sn-doped In2O3 NWs under H2S between 300 to 600 °C resulted in an increase of conductivity and band edge emission, respectively. However, there are no investigations into the conversion of β-Ga2O3 into β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs under H2S. Ga2S3 is a III-VI semiconductor which can have the monoclinic, hexagonal, or cubic crystal structure [7]. Among these, the most stable crystal structure is monoclinic of Ga2S3 which has a direct wide-band gap of 3.4 eV [8, 9] but contains many vacancies in its Ga sub lattice and consequently exhibits defect emission similar to oxides [10, 11]. Despite this, Ga2S3 has been investigated for light-emitting diodes and photovoltaic devices while recently, it was shown that Ga2S3 has a large second-harmonic generation efficiency ideally suited for nonlinear optics [12]. The optical properties of single crystals and epitaxial layers of Ga2S3 have been investigated using steady-state absorption-transmission and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy and exhibit blue and red emission at 10 K due to deep donor-to-acceptor transitions related to S and Ga vacancies [8, 10, 11]. In contrast, one-dimensional GaS or Ga2S3 nanotubes so far have been shown to exhibit PL between 450–600 nm [13–15], but there are no detailed investigations on the optical properties of GaS or Ga2S3 NWs using steady-state or transient optical spectroscopy which could provide insight into their fundamental properties and potential device applications.

Consequently, we have undertaken an investigation into the post growth processing of β-Ga2O3 NWs under H2S between 400–600 °C and its effect on the optical properties using ultrafast absorption spectroscopy in conjunction with steady-state and time-resolved PL. We find that the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs exhibit state filling following carrier excitation at 266 nm (λ E) for probing wavelengths (λ p) between 340 to 450 nm corresponding to states lying energetically below but near the conduction band edge. In addition, the β-Ga2O3 NWs exhibited broad PL with a maximum at 435 nm and lifetime of 2.4 ns. Similar results have also been observed for the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs after post growth processing under H2S at 400 °C. In contrast, the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained under H2S at 500 to 600 °C exhibit free carrier absorption for λ p > 500 nm and state filling for λ p < 450 nm related to the formation of Ga2S3. This is accompanied by a suppression of the broad PL at 435 nm and the emergence of strong emission at ≈ 680 nm with a much longer lifetime of 19 μs. In addition, at low temperature, a relative narrow emission at 428 nm emerges resulting from near band edge states to the acceptor states located near the valance band of the β-Ga2S3.

Methods

β-Ga2O3 NWs were grown by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition at 800 °C and 1mBar for 60 min on Si(001) using a 1-nm layer of Au as catalyst and exactly the same growth conditions used for Sn-doped In2O3 NWs as described in detail elsewhere [5]. The morphology of the NWs were then examined with a TESCAN scanning electron microscope (SEM) while their crystal structure and phase purity were investigated using a SHIMADZU, XRD-6000, X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Ka source, by performing a scan of θ-2θ in the range between 10° and 80°. The dynamic behavior of carriers within the NWs was investigated through the temporal behavior of ultrafast time-resolved differential absorption obtained from simultaneous measurements of time-resolved differential transmission and reflection [16, 17]. The experiments were carried out using a Ti: Sapphire ultrafast amplifier system generating 100-fs pulses at 800 nm and running at a repetition rate of 1 kHz. Nonlinear crystals were used to generate 266 nm for the purpose of exciting the NWs whereas part of the fundamental and second-harmonic generation at 400 nm was used to generate a super continuum light for probing different energy states. Measurements were carried out using a typical pump-probe optical setup in a non collinear configuration. Photoluminescence were carried out utilizing a spectrometer equipped with an intensified charge-coupled device camera. The low-temperature measurements were carried out using a closed cycle refrigerator capable of cooling the sample to temperatures below 10 K.

Results and Discussion

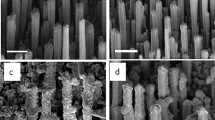

A typical SEM image of the β-Ga2O3 NWs which had diameters of 50–100 nm and lengths of up to 100 μm is shown as an inset in Fig. 1a.

a XRD of β-Ga2O3 NWs before and after post growth processing under H2S at 400, 500, and 600 °C for 60 min. Black arrows at the top correspond to β-Ga2O3 and gray to β-Ga2S3 while the Al peaks belong to the holder; inset shows a SEM image of the β-Ga2S3 /β-Ga2O3 NWs at 500 °C. b Steady-state transmission of as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs at 300 K and β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained under H2S at 400, 500, and 600 °C. The optical band gap is estimated from the x intercept of the inset, where (αhν)2 is plotted as a function of photon energy

The β-Ga2O3 NWs have a monoclinic crystal structure similar to that obtained previously [6] and were exposed to 50 sccm of H2S at 400, 500, and 600 °C for 60 min using a ramp rate of 10 °C/min which resulted in the formation of the β-Ga2O3/β-Ga2S3 NWs as shown by the XRD of Fig. 1a. In particular, we observe peaks belonging to β-Ga2O3 but also the emergence of monoclinic β-Ga2S3 due to the diffusion of S into β-Ga2O3. Ga2S3 is a III-VI defect semiconductor which can have the monoclinic, hexagonal, or cubic crystal structure. Among these, the most stable crystal structure of Ga2S3 is the monoclinic phase. We observe a suppression of most peaks belonging to β-Ga2O3 with increasing temperature although a few remain at 600 °C which means that high temperatures are necessary to achieve complete conversion into Ga2S3. Interestingly, the β-Ga2O3/β-Ga2S3 NWs remained one-dimensional up to 600 °C in contrast to SnO2 and Sn-doped In2O3 NWs which were eliminated under H2S due to their reduction by H2 [18, 19]. Here, we should point out that post growth processing of MO NWs such as Sn-doped In2O3 at elevated temperatures resulted n the formation of crystals on the surface and not a conformal or epitaxial like shell [19]. The lattice constants of β-Ga2O3 are a = 12.23 Å, b = 3.04 Å, and c = 5.80 Å with β = 103.7° while β-Ga2S3 have lattice constants of a = 11.11 Å, b = 9.58 Å, and c = 6.4 Å with β = 141.15°, so one expects interfacial stress due to the lattice mismatch between the β-Ga2O3 and β-Ga2S3. The band line-up and the effect of strain on the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 heterojunction is not known, but the energy band gap and work function of Ga2O3 is 4.5 eV and 4.1 eV, respectively [20], while the energy band gap of Ga2S3 is smaller and equal to 3.42 eV. Assuming that the work functions are similar, the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 heterojunction is expected to be type I. It is also useful to note that F.Säuberlich et al. [21] showed that the large interface dipole moments exist between metal oxides and chalcogenides resulting into small conduction band discontinuities. Steady-state absorption measurements (Fig 1b) through the NWs grown on fused silica suggest a band gap at ≈ 4.55 eV for the β-Ga2O3 and 400 °C NWs which decreased to 3.1 eV after post growth processing under H2S at 500 and 600 °C consistent with the formation of β-Ga2S3. Furthermore, there appears to be a broad absorption below the band edge for all the samples most likely due to the defect states present. Unfortunately, the absorption spectra for the β-Ga2O3/β-Ga2S3 NWs do not provide any clear evidence of the type of band offset that may exist between this hetero-structure [22]. Nevertheless, transient PL and differential absorption measurements indicate that the main contribution of both signals is coming from Ga2S3 suggesting a type I heterojunction. This is confirmed since the observed time constants in the decays in these signals remain the same with increasing post growth processing temperature from 500 to 600 °C and higher where the NW structure is completely converted to Ga2S3.

Photoluminescence of the as-grown β-Ga2O3 and β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained at 400, 500, and 600 °C is shown in Fig 2a. The as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs exhibit broad PL with a maximum at ≈ 435 nm, which is attributed to transitions between donor-like states related to oxygen vacancies (VO) and acceptor-like states due to gallium vacancies (VGa) or gallium-oxygen vacancy pairs (VGa-VO) [23]. We observe a small red shift of the PL from 2.9 to 2.8 eV after post growth processing under H2S at 400 °C and a tenfold reduction in intensity. However, the suppression of the PL at ≈ 2.9 eV was accompanied by the emergence of red emission at ≈ 1.8 eV following post growth processing of the β-Ga2O3 NWs under H2S at 500 and 600 °C as shown in Fig. 2a.

a PL of as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs at 300 K and β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained under H2S at 400, 500, and 600 °C using λ E = 266 nm; inset shows the temperature-dependent PL of the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs, whereas b and its inset shows temperature-dependent PL of the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs at 500 and 400 °C, respectively

This red emission is attributed to transitions between donor-like states, located ≈ 1.1 eV below the conduction band edge, to acceptor states ≈ 0.4 eV above the valance band edge in Ga2S3 [10, 11]. It should be noted that the PL of the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs increased by a factor of two upon decreasing the temperature down to 10 K (inset Fig 2a). On the other hand, we observed a sixfold increase of the 680-nm peak for the NWs processed under H2S at 500 and 600 °C, whereas new peaks appear at 428 nm (2.9 eV) and 620 nm (2.0 eV) for temperatures below 100 K as shown in Fig. 2b.

The temperature dependence of the PL peak intensity can be described by [24]

where I(T) is the intensity as a function of temperature T, C is a constant, kB is Boltzmann constant, and E act is the activation energy. A fit of this equation to the data provided an activation energy of 18 meV for the 428-nm PL peak.

Given the activation energy, we believe that the emission occurs from states just below the band edge to acceptor states located around the 0.4 eV band. Our findings are consistent with those described by Yoon et al. [10] for Ga2S3 who identified at 10 K two transitions of 1.93 and 2.9 eV between an acceptor state at 0.42 eV above the valence band edge and donor states at 0.1 eV and 1.1 eV below the conduction band. Furthermore, it appears from our findings that the occupation of the lower-end energy states in the 0.4 eV band at low temperatures results in a substantial increase in the 680-nm line as well as the new emission emerging at 620 nm at <100 K. These trends are consistent with the findings of Ho and Chen [8] who observed PL at 1.99 and 2.79 eV at low temperatures attributed to the formation of sulfur vacancies (VS) as well as the existence of Ga vacancies (VGa) which form donor and acceptor levels, respectively. We should point out that in their work on the high quality Ga2S3 crystal [8], they have observed a broad emission around 500 nm at room temperature in contrast to the observed emission at 680 nm from the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs (Fig. 2). It should be emphasized that all previous investigations on one-dimensional GaS and α-Ga2S3 showed PL between 450–600 nm or 2.1–2.8 eV, so here, we show that β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 can exhibit red emission at room temperature which makes them attractive not only for the applications in sensors and non-toxic biomedical imaging but also for down-conversion in solar cells.

In order to gain a better understanding of the optical properties, time-resolved differential absorption measurements were carried out using excitation at 266 nm and probing wavelengths between 340 to 850 nm. The differential absorption versus optical delay acquired from the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs and the Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained after processing with H2S at 400 and 500 °C are shown in Figs. 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

a Differential absorption of the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs versus optical delay using λ E = 266 nm and λ p = 340 to 850 nm. The diagram shows the various processes following the photo-excitation of the β-Ga2O3 NWs; inset shows traces for λ p >500 nm on an expanded scale (the same units). b Differential absorption measurements with λ p = 340 nm in β-Ga2O3 NWs for a range of fluences. The inset shows the normalized differential absorption for comparison

The various traces in each case correspond to different λ p over a time span of 10 to 500 ps and were obtained using a fluence of 115 μJ/cm2. The value of the fluence was chosen for best signal-to-noise ratio with negligible nonlinear recombination as clearly seen from the normalized fluence measurements in the inset of Fig 3b. Similar behavior was observed for the different probing wavelengths and samples for this range of fluence.

For the shortest probing wavelengths, we observe a pulse width-limited, sharp decrease in the induced absorption followed by a recovery toward equilibrium over a time scale of hundreds of ps. These changes in absorption are associated with the excitation of electrons and holes in the β-Ga2O3 and Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs by photons resulting in the generation of non-equilibrium carriers. These non-equilibrium carriers will re-distribute themselves among energy states that are normally unoccupied under equilibrium conditions. This will appear as a decrease in the absorption (state filling) at the energy states that are being probed. The recovery of this absorption change will be a direct measure of the time required by the photo-generated carriers to move out of the occupied states. In the case of the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs, we observe a strong negative differential absorption for λ p < 450 nm corresponding to state filling of the energy states located below the conduction band of the β-Ga2O3 NWs as shown in Fig. 3. The relaxation of the non-equilibrium carriers can be described by a tri-exponential decay with time constants (τ) and amplitudes (α) of τ 1 = 2–4 ps (α 1 = 28–35 %), τ 2 = 68–85 ps (α 2 = 31–50 %) and τ 3 = 1915–2050 ps (α 3 = 20–41 %). Both τ 1 and τ 2 are related to non-radiative, re-distribution of photo-generated carriers in point defect or surface states, depicted schematically in the energy band diagram shown as an inset in Fig. 3, whereas τ 3 is most likely associated with radiative recombination. For λ p = 550 to 600 nm, the observed differential absorption is relatively small and is associated with the Au plasmon resonance [6]. For longer λ p, the signal appears to be weaker and is associated with what is known as “free carrier absorption”. We should point out here that free carrier absorption is considered as a competing process to state filling, and it occurs due to secondary excitation of the photo-generated carriers by the probing photons from their initial states to higher energy states. This phenomenon will result in a positive change in the induced absorption.

Given that state filling is observed for λ p corresponding to energies that are smaller than the energy band gap of β-Ga2O3, it is evident that the β-Ga2O3 NWs contain states residing energetically in the upper half of the gap consistent with the broad PL shown in Fig. 2.

Similar trends were also observed in Fig. 4 for the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained after processing under H2S at 400 °C which resulted into a slight reduction of differential absorption and a faster decay of electrons occupying energetically higher states, compared to the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs.

The decay times are similar, i.e., τ 1 = 3.5–5.5 ps (α 1 = 50–52 %), τ 2 = 59–95 ps (α 2 = 34–41 %) and τ 3 = 1950–2010 ps (α 3 = 10–22 %), but the strength of τ 1 increased from 30 to 50 % consistent with the suppression of radiative recombination and blue PL which occurs upon processing the β-Ga2O3 NWs at 400 °C as shown in Fig. 2. This is also consistent with the fact that there is noticeable state filling observed for longer λ p in contrast to the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs, and it is clearly due to the formation of defect states.

Differential absorption measurements for the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs after exposure to H2S at 500 °C are shown in Fig. 5. Again, state filling is observed for λ p < 450 nm, but in this case, the main signal is coming from the β-Ga2S3 where the carriers are generated above the conduction band and relaxation takes place on a very short time scale with τ 1 = 1 ps (α 1 = 25–35 %), τ 2 = 35 ps (α 2 = 34–50 %) and τ 3 = 145–167 ps (α 3 = 8–20 %).

For the larger probing wavelengths, (λ p) free carrier absorption is dominant. It appears that the β-Ga2S3 formed during the processing of the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs under H2S plays a crucial role in the carrier dynamics. The differential absorption signal for λ p > 500 nm appears to be much larger than the contribution from the β-Ga2O3. The donor states in β-Ga2S3 [10, 11] which are located approximately 1.1 eV from the conduction band edge are populated following excitation, and as a result, the carriers undergo a secondary excitation by the probing beam back into the conduction band. Further evidence of this was observed for the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained at 600 °C where differential absorption measurements reveal an increase in the free carrier absorption signal in the long wavelength range. The free carrier absorption may be described well with a two exponential function (α 0 + α 1 e -t/τ 1 + α2 e -t/τ 2) and a constant α 0 associated with the very long radiative emission, consistent with the lifetime of the observed red emission (~19 μs) from the 1.1-eV donor state. The time constants have a range of values of τ 1 = 1.2–2.9 ps (α 1 = 22–25 %), τ 2 = 49–87 ps (α 2 = 49–54 %) and a non-zero α 0 constant (21–29 %). Here, we should also point out that the low-temperature pump-probe measurements carried out in these samples revealed similar temporal behavior with time constants approximately 10-15 % longer.

In order to investigate the carrier dynamics on a longer time scale in the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs, transient PL measurements were obtained using λ p = 266 nm and 100-fs pulses. Room temperature (RT), transient, or time-resolved PL (TRPL) of the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs reveal a single exponential decay with a time constant of 2.4 ns. We should also point out that TRPL at 10 K gave an identical decay and a twofold increase in the PL intensity. Similarly, RT TRPL of the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs exposed to H2S at 400 °C consists of a single exponential decay with a time constant of 2.0 ns. On the other hand, TRPL measurements at room temperature of the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained at 500 °C show a single exponential decay at 680 nm with a much larger time constant of 19 μs (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7a).

The corresponding TRPL at 10 K reveals a new peak at 430 nm following a double exponential decay with time constants 6 ns (62 %) and 42 ns (38 %) (Fig. 7b). The red PL emission can be expressed by a double exponential decay with time constants of 1.8 μs (32 %) and 26.9 μs (68 %) (Fig. 7b). Similar results have also been observed for the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs at 600 °C. The 26.9-μs time constant is mainly associated with the red emission, and as expected, it is longer at low temperature whereas the short time constant is most likely associated with carriers moving into another state most likely non-radiative.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have grown β-Ga2O3 NWs at 800 °C which were converted to β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs by post growth processing under H2S between 400–600 °C for 60 min. We find that the as-grown β-Ga2O3 NWs exhibit state filling following carrier excitation for probing wavelengths between 340 to 450 nm corresponding to states lying energetically below the conduction band edge. In addition, the β-Ga2O3 NWs exhibited broad PL with a maximum at 435 nm (2.85 eV) and lifetime of 2.4 ns. Similar results have also been observed in the case of β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained under H2S at 400 °C. In contrast, the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs obtained under H2S at 500 to 600 °C exhibit state filling for λ p < 450 nm related to the formation of Ga2S3 and free carrier absorption for λ p > 500 nm related secondary excitations from formation mid-gap states in Ga2S3 located 1.1 eV below the conduction band edge. Furthermore, this is accompanied by a suppression of the broad PL at 435 nm and the emergence of strong emission at ≈ 680 nm (1.8 eV) with a much longer lifetime of 19 μs. This long-life emission is associated with the transition of carriers from the 1.1 eV band to a band located at 0.4 eV above the valence band edge of Ga2S3. Finally, we like to point out that the room temperature red emission of the β-Ga2O3/Ga2S3 NWs may be used in various applications including sensors, non-toxic biomedical imaging, and energy down-conversion in nanowire solar cells.

Abbreviations

- NWs:

-

nanowires

- PL:

-

photoluminescence

- MO:

-

metal oxide

- SEM:

-

scanning electron microscope

- λ E :

-

excitation wavelength

- λ p :

-

probing wavelength

- RT:

-

room temperature

- LT:

-

low temperature

References

Zhai T, Fang X, Liao M, Xu X, Zeng H, Yoshio B, Golberg D. A Comprehensive Review of One-Dimensional Metal-Oxide Nanostructure Photodetectors, Sensors 2009;9:6504-29.

Garnett EC, Brongersma ML, Cui Y, McGehee MD. Nanowire Solar Cells. An Rev Mat Res. 2011;41:269-295.

Tsokkou D, Othonos A, Zervos M. Carrier dynamics and conductivity of SnO2 nanowires investigated by time-resolved terahertz spectroscopy. Appl Phys Lett. 2012;100:133101-4.

Tsokou D, Zervos M, Othonos A. Ultrafast time-resolved spectroscopy of In2O3 nanowires. J Appl Phys. 2009;106:084307.

Zervos M, Mihailescu CN, Giapintzakis J, Luculescu CR, Florini N, Komninou Ph, Kioseoglou J, Othonos A. Broad compositional tunability of indium tin oxide nanowires grown by the vapor liquid-solid mechanism. Appl Phys Lett Mat. 2014;2:056104.

Othonos A, Zervos M, Christofides C. Carrier dynamics in β-Ga2O3 nanowires. J Appl Phys. 2010;108:124302.

Lieth RMA, Heijligers HJM, v.d. Heijden CWM. The P‐T‐X Phase Diagram of the System Ga‐S, J Electrochem Soc. 1966;8:798-801.

Ho C-H, Chen H-H. Optically decomposed near-band-edge structure and excitonic transitions in Ga2S3. Scientific Report. 2014;4:6143-51.

Madelung O, Poerschke R (eds) 1992. Semiconductor: Other than Group IV Elements and III-V Compounds (Berlin: Springer).

Yoon C-S, Medina FD, Martinez L, Park T-Y, Jin M-S, Kim W-T. Blue photoluminescence of α-Ga2S3, α-Ga2S3:Fe2+ single crystals. Appl Phys Lett. 2003;83:1947-49.

Aono T, Kase K Green Photoemission of α-Ga2S3 Crystals. Solid State Comm. 1992;81:303-5.

Liu HF, Antwi KKA, Yakovlev NL, Tan HR, Ong LT, Chua SJ, Chi DZ. Synthesis and Phase Evolutions in Layered Structure of Ga2S3 Semiconductor Thin Films on Epiready GaAs (111) Substrates ACS. Appl Mater Interfaces 2014;6:3501-07.

Panda SK, Datta A, Sinha G, Chaudhuri S, Chavan PG, Patil SS, More MA, Joag DS, Synthesis of well-crystalline GaS nanobelts and their unique field emission behavior. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:6240-44.

Hu PA, Liu YQ, Fu L, Cao LC, Zhu DB. GaS multi-walled nanotubes from the lamellar precursor. Appl Phys A. 2005;80:1413-17.

Gautam UK, Vivekchand SRC, Govindaraj A, Kulkarni GU, Selvi NR, Rao CNR. Generation of Onions and Nanotubes of GaS and GaSe through Laser and Thermally Induced Exfoliation. J Am Chem. Soc. 2005;127:3658-59.

Othonos A, Zervos M, Pervolaraki M. Ultrafast Carrier Relaxation in InN Nanowires Grown by Reactive Vapor Transport. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2009;4:122-29.

Othonos A. Probing ultrafast carrier and phonon dynamics in semiconductors. J Appl Phys. 1998;83:1789-1830.

Zervos M, Mihailescu C, Giapintzakis J, Othonos A, Luculescu C. Surface passivation and conversion of SnO2 to SnS2 nanowires. Materials Science and Engineering B. 2015;198:10-13.

Zervos M, Mihailescu C, Giapintzakis J, Othonos A, Travlos A. Electrical, structural and optical properties of sulfurised Sn doped In2O3 nanowires. Nanoscale Research Letters. In Press (2015).

Mohamed M, Irmscher K, Janowitz C, Galazka Z, Manzke R, Fornari R. Schottky barrier height of Au on the transparent semiconducting oxide β-Ga2O3. Appl Phys Lett. 2012;101:132106.

Säuberlich F, Klein A. Band Alignment at Oxide Semiconductor Interfaces, MRS Proceedings. 2003;763.

Dooley CJ, Dimitrov SD, Fiebig T Ultrafast Electron Transfer Dynamics in CdSe/CdTe Donor−Acceptor Nanorods. Phys Chemistry Letters C. 2008;112:12074-76.

Liang CH, Meng GW, Wang GZ, Wang YW, Zhang LD, Zhang SY. Catalytic synthesis and photoluminescence of β-Ga2O3 nanowires. Appl Phys Lett. 2001;78:3202.

Shu GW, Wu PF, Lo MH, Shen JL, Lin TY, Chang HJ, Chen YF, Shih CF, Chang CA, Chen NC. Concentration dependence of carrier localization in InN epilayers, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006; 89: 131913.

Acknowledgements

The work in this article was partially supported by the European Regional Development Fund and the Research Promotion Foundation of Cyprus under the grant ΑΝΑΒΑΘΜΙΣΗ/ΠΑΓΙΟ/0308/02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

KMO, CC, and AO were responsible for the ultrafast and PL measurements. MZ was responsible for the growth and structural characterization of the nanowires. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Othonos, K.M., Zervos, M., Christofides, C. et al. Ultrafast Spectroscopy and Red Emission from β-Ga2O3/β-Ga2S3 Nanowires. Nanoscale Res Lett 10, 304 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1016-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1016-y