Abstract

Strain analysis has significance both for tailoring material properties and designing nanoscale devices. In particular, strain plays a vital role in engineering the growth thermodynamics and kinetics and is applicable for designing optoelectronic devices. In this paper, we present a methodology for establishing the relationship between elastic bond constants and measurable parameters, i.e., Poisson’s ratio ν and systematic elastic constant K. At the atomistic level, this approach is within the framework of linear elastic theory and encompasses the neighbor interactions when an atom is introduced to stress. Departing from the force equilibrium equations, the relationships between ν, K, and spring constants are successfully established. Both the two-dimensional (2D) square lattice and common three-dimensional (3D) structures are taken into account in the procedure for facilitating, bridging the gap between structural complexity and numerical experiments. A new direction for understanding the physical phenomena in strain engineering is established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Strain always acts as a driving force in strain-engineered nanostructure formation [1–7] and plays a crucial role in nanoscale device designing. By manipulating strain-dependent growth kinetic and thermodynamic conditions, technically tailoring size, shape, and position of the growing structures becomes accessible. Accordingly, the energy band structures of the tailored structures can thus be modified. When shedding light on device designing, in particular, the strain-engineered formation of heterostructures, junctions, and variable composition profiles in quantum dots (QDs) and nanowires (NWs) during epitaxial growth [8, 9], strain provides a key strategy for producing optimal nanophotonic and nanoelectronic materials, including high-efficiency blue and green light-emitting diodes (LEDs) [10, 11], visible lasers [12–14], and high-efficiency solar cells [15]. Moreover, studies on the strain effect incorporated in two-dimensional (2D) materials [16–18] and topological insulators [19–21] also open doors to new classes of electronic and spintronic devices. Therefore, an understanding of the strain effects is highly essential.

Many efforts have been devoted to tackling the strain effects within epitaxial systems [22–29]. Among them, finite element (FE) method based on continuum elasticity and atomistic strain calculations are most commonly used. The FE method generally developed for macroscopic structures is integral to strain effect studies. However, to obtain accurate results, a smaller grid size is always favorable, which leads to increased computer memory and time. For the atomistic strain calculations, the bonds between atoms are often considered as ideal springs. All through the pioneering work by Keating [28] and other extended works, the empirical or semi-empirical interatomic potentials that are difficult to measure experimentally are always essential for the strain calculation. Thus, in the atomistic calculations, the lack of understanding of the elusive interaction coefficients may hinder better comprehension of the elastic properties.

In this work, we establish a connection between the Poisson’s ratio, a measurable elastic constant [30], and the spring constants used in the atomistic strain simulations, within the framework of linear elasticity theory. At the atomistic level, Poisson’s effect is caused by infinitesimal displacements of atoms thus the stretching of atomistic bonds within the material lattice to accommodate the stress. When the bonds in the stress direction are elongated or compressed, their counterpart in the perpendicular direction will be correspondingly shortened or lengthened. Drawing from the atomistic strain method [26], we considered the lattice bonds as ideal springs, connecting all the neighboring atoms and are within elastic deformation limit upon exerting external force. Our description of the elastic constants has a microscopic interpretation that incorporates all nearest and diagonal bond springs. Under the definition of Hooke’s law, the relationship between stress and responded strain is simply built, resulting in force balance equations, which is vital to formulating the relationship between the Poisson’s ratio and the spring constants.

Methods

Focusing on deriving the spring constants in the atomistic strain method using the Poisson’s ratio, we give insights to building up the formulism for elasticity quantities based on the proposed approach. The explicit methodology presented here aims to develop a useful tool that can provide the inputs for atomistic strain analysis instead of a specific model. Drawing from the linear elasticity, the analytical results will facilitate one to directly use these inputs for most general crystal structures. Based on the implementation of our derivation, the validation of our formulated results is succeeded in our previous studies [27, 31, 32]; the elastic strain is well calculated utilizing our derived inputs. In the following derivation, both the common two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) crystal lattices are considered in our calculations. In comparison with the effect on atomistic strain analysis caused by nearest neighbors, some lower order quantities, like bond angle and nonlinear interaction, are ignored in our derivation. Although our result has its limitation when dealing with amorphous materials and systems with strong metallic bonds, it is constructed based on some general crystal lattices. It performs well in most materials with strong chemical bond. The derived explicit results are applicable to numerical calculation and computations, thus paving way for a more detailed exploration of strain-related mechanisms.

Results and Discussion

2D Square Lattice

For a clear and easy to understand example of the general derivation to obtain the microscopic constants, we start with the 2D square lattice. The 2D square lattice is the most commonly used 2D simulation cell for qualitative studies of the general mechanisms. This simple generic 2D structure should capture the essential steps in the formulation and guide the study for more complicated systems.

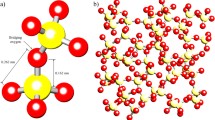

Assuming that the displacements of atoms, thus the infinitesimal changes of bond lengths, are along the axial direction, Poisson’s ratio ν is often expressed as ν = − dε trans/dε axial, where ε trans and ε axial represent the transverse and axial strains, respectively. The unit cell of a 2D square system demonstrated in Fig. 1a is composed of four atoms and has two types of spring bonds along the side and diagonal directions, respectively, with constants K 1 and K 2. By the Poisson’s ratio definition, when a stretching force F is exerted along the y direction, the resulted two length variations along x and y directions are expressed as δ 1 and δ 2, respectively, in which a represents the lattice constant and δ 1,2 ≪ a. The change in diagonal length can be easily obtained by the simple trigonometric function. The total diagonal bond length is \( \sqrt{{\left(a+{\delta}_1\right)}^2+{\left(a+{\delta}_2\right)}^2} \). Owing to the minuscule length variations, it can be approximately expressed as \( \sqrt{{\left(a+{\delta}_1\right)}^2+{\left(a+{\delta}_2\right)}^2}\cong \sqrt{2}a+\frac{\delta_1+{\delta}_2}{\sqrt{2}} \) by ignoring the small second-order terms. Thus, the bond length change in the diagonal direction is described as \( {\delta}_{\mathrm{diag}}=\left({\delta}_1+{\delta}_2\right)/\sqrt{2} \).

Next, we separate one atom (upper left in Fig. 1a) in this system and apply force balance analysis, shown in Fig. 1b. We get f 1 + f 3 sin θ = F and f 2 + f 3 cos θ = 0, in which f 1 = K 1 δ 1, f 2 = K 1 δ 2, and \( {f}_3={K}_2{\delta}_{\mathrm{diag}}={K}_2\cdot \left({\delta}_1+{\delta}_2\right)/\sqrt{2} \) by Hooke’s law. Since δ 1,2 ≪ a, θ ≈ 45°. Solving the above equations, we get the expression of Poisson’s ratio ν and the comprehensive elastic constant K of the whole system along the force direction

Note that both ν and K are measurable quantities in the lab. By solving the equation sets (1) and (2), finally, we get the relationship between K 1,2, K, and ν

Note that if K 2 = 0, then ν = 0 and K = K 1 as needed.

Simple Cubic Lattice

Having set up the 2D square lattice as a reference, we now derive the expressions of spring constants in terms of the Poisson’s ratio for common 3D crystal structures (shown in Fig. 2) following the established procedure.

We commence with choosing the simple cubic (SC) structure illustrated in Fig. 2a. We consider three distinct types of elastic springs along edge, face diagonal, and body diagonal directions, and the three main related coefficients are defined as K 1, K 2, and K 3, respectively. Following the practice used for 2D cases, we set the displacement values δ z = δ 1 ≪ a and δ x = δ y = δ 2 ≪ a, whiles the remaining values in the diagonal directions can be easily derived via geometry analysis.

From equilibrium conditions, the force balance equations are

According to Eq. (4b), the Poisson’s ratio is acquired through

Now, we substitute \( {\delta}_2=-\frac{3{K}_2+2{K}_3}{6{K}_1+9{K}_2+4{K}_3}{\delta}_1 \) into Eq. (4a), and the comprehensive elastic constant along z-axis is

It is noticeable here that if K 2 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_3}{3{K}_1+2{K}_3},K=\frac{3{K_1}^2+3{K}_1{K}_3}{3{K}_1+2{K}_3} \); if K 3 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_2}{2{K}_1+3{K}_2},\ K=\frac{2{K_1}^2+2{K_2}^2+5{K}_1{K}_2}{2{K}_1+3{K}_2} \); and if K 2 = K 3 = 0, then ν = 0, K = K 1 as required. Although K 1, K 2, and K 3 are not attainable at the same time, the relationship can be used to set up the calculation inputs if one of the interactions is much weaker than the others.

Body-Centered Cubic Lattice

Now, we pay attention to calculating the elastic constants of the body-centered cubic (BCC) lattice which is demonstrated in Fig. 2b.

Studying the balanced force conditions using the same definition of displacements, we have

in z direction and

in x and y directions.

From Eq. (7b), we obtain the Poisson’s ratio,

Substituting \( {\delta}_2=-\frac{3{K}_2+{K}_3}{6{K}_1+9{K}_2+2{K}_3}{\delta}_1 \) into the balanced condition Eq. (7a), the comprehensive elastic constant along z direction is described as

It is observed here that if K 2 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_3}{6{K}_1+2{K}_3},K=\frac{6{K_1}^2+3{K}_1{K}_3}{6{K}_1+2{K}_3} \); if K 3 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_2}{2{K}_1+3{K}_2},\ K=\frac{2{K_1}^2+2{K_2}^2+5{K}_1{K}_2}{2{K}_1+3{K}_2} \); and if K 2 = K 3 = 0, then ν = 0, K = K 1 as required. Finally, the connection between the Poisson’s ratio and elastic constant is established for BCC lattice.

Face-Centered Cubic Lattice

Here, we will show insights into establishing the relationship between the Poisson’s ratio and the elastic constant of the face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice illustrated in Fig. 2c. Similarly, given the minor length changes in response to external force, we get the Poisson’s ratio by analyzing the force equilibrium conditions. The balanced equation in z direction is

and in x and y directions, the equation is given as

And then, the Poisson’s ratio is expressed as

Then, we undertake substitution operations, replacing δ 2 with \( {\delta}_2=-\frac{3{K}_2+4{K}_3}{12{K}_1+9{K}_2+8{K}_3}{\delta}_1 \) in Eq. (10a). Thus the comprehensive elastic constant along z axis is

Here the observation about the relationship show that if K 2 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_3}{3{K}_1+2{K}_3},\ K=\frac{3{K_1}^2+3{K}_1{K}_3}{3{K}_1+2{K}_3} \); if K 3 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_2}{4{K}_1+3{K}_2},\ K=\frac{4{K_1}^2+{K_2}^2+5{K}_1{K}_2}{4{K}_1+3{K}_2} \), and if K 2 = K 3 = 0, then ν = 0, K = K 1 as required. Here the related equations about Poisson’s ratio and elastic constant are built up.

Diamond Lattice

Now we consider the elastic constants of diamond lattice generally adopted in many materials, including α-tin, the semiconductors silicon and germanium, and silicon/germanium alloys in any proportion. The diamond structure is sketched in Fig. 2(d), and we also define three various spring bond constants along the nearest bond directions, which are labeled as K 1, K 2, and K 3 respectively. Apparently, the force balance equations are

in z direction, and

in x and y direction.

According to Eq. (13b) above, Poisson’s ratio is written as

Next, we replace δ 2 in Eq. (13a) with \( {\delta}_2=-\frac{3{K}_2+{K}_3}{12{K}_1+9{K}_2+2{K}_3} \). After substituting, we obtain the comprehensive elastic constant along z direction

It is recognized that if K 2 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_3}{12{K}_1+2{K}_3},\ K=\frac{12{K_1}^2+3{K}_1{K}_3}{12{K}_1+2{K}_3} \), if K 3 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_2}{4{K}_1+3{K}_2},\ K=\frac{4{K_1}^2+{K_2}^2+5{K}_1{K}_2}{4{K}_1+3{K}_2} \), and if K 2 = K 3 = 0, then ν = 0, K = K 1 as required. Finally, we attain the relationship between Poisson’s ratio and elastic constant for diamond lattice.

Hexagonal Close-Packed Lattice

We will concentrate on creating the formulation of Poisson’s ratio and elastic constants for hexagonal close-packed (HCP) lattice, which exist in many single element metals, such as Magnesium (Mg), Titanium (Ti), Hafnium (Hf), and Zinc (Zn). There are three different spring bond constants shown in Fig. 2. Here, we still chose Cartesian coordinates in order to facilitate the calculation.

In accordance with the same definition of tiny length changes, we obtain the force balance equations

in z direction and

in x and y directions.

Through Eq. (16b), we get the expression for the Poisson’s ratio

Now, we replace \( {\delta}_2=-\frac{9{K}_2+4{K}_3}{36{K}_1+27{K}_2+8{K}_3}{\delta}_1 \) in the balanced condition Eq. (16a), and then the comprehensive elastic constant along z direction is written as

Notably, from the above equations, we see that if K 2 = 0, then \( \nu =\frac{K_3}{9{K}_1+2{K}_3},\ K=\frac{9{K_1}^2+3{K}_1{K}_3}{9{K}_1+2{K}_3} \); if K 3 = 0, then \( K=\frac{4{K_1}^2+{K_2}^2+5{K}_1{K}_2}{4{K}_1+3{K}_2} \); and if K 2 = K 3 = 0, then ν = 0, K = K 1 as required.

Consequently, we have established the correlations between the Poisson’s ratio and spring bond constant for all the 3D systems exemplified in Fig. 2.

Conclusions

We successfully proposed a methodology calculating the spring constants between neighbored atoms in atomistic strain analysis, using quantifiable physical quantities, i.e., Poisson’s ratio ν and comprehensive elastic constant K. This method describes the neighbored atom interactions with different spring bonds and gives insight into the force balance conditions, which contribute to obtaining the plausible results. The 2D square lattice and the ordinary 3D lattices are explicated. This derivation process gives a straightforward view of understanding the elastic constant connections in these systems and is evidentially useful for numerical calculation and computations. This will pave way for a more detailed exploration of strain-engineered nanostructure formation and functionalization of electronic devices.

References

Liu F, Lagally MG (1997) Self-organized nanoscale structures in Si/Ge films. Surf Sci 386(1–3):169–181. doi:10.1016/s0039-6028(97)00303-8

Medeiros-Ribeiro G, Bratkovski AM, Kamins TI, Ohlberg DAA, Williams RS (1998) Shape transition of germanium nanocrystals on a silicon (001) surface from pyramids to domes. Science 279(5349):353–355. doi:10.1126/science.279.5349.353

Moison JM, Houzay F, Barthe F, Leprince L, Andre E, Vatel O (1994) Self-organized growth of regular nanometer-scale InAs dots on GaAs. Appl Phys Lett 64(2):196–198. doi:10.1063/1.111502

Xie QH, Madhukar A, Chen P, Kobayashi NP (1995) Vertically self-organized InAs quantum box islands on GaAs(100). Phys Rev Lett 75(13):2542–2545. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.2542

Tersoff J, Teichert C, Lagally MG (1996) Self-organization in growth of quantum dot superlattices. Phys Rev Lett 76(10):1675–1678. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.1675

Teichert C, Lagally MG, Peticolas LJ, Bean JC, Tersoff J (1996) Stress-induced self-organization of nanoscale structures in SiGe/Si multilayer films. Phys Rev B 53(24):16334–16337. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.53.16334

Ross FM, Tersoff J, Tromp RM (1998) Coarsening of self-assembled Ge quantum dots on Si(001). Phys Rev Lett 80(5):984–987. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.984

Utrilla AD, Ulloa JM, Guzman A, Hierro A (2014) Long-wavelength room-temperature luminescence from InAs/GaAs quantum dots with an optimized GaAsSbN capping layer. Nanoscale Res Lett 9:36. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-9-36

Persichetti L, Sgarlata A, Mori S, Notarianni M, Cherubini V, Fanfoni M, Motta N, Balzarotti A (2014) Beneficial defects: exploiting the intrinsic polishing-induced wafer roughness for the catalyst-free growth of Ge in-plane nanowires. Nanoscale Res Lett 9:358. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-9-358

Duan XF, Huang Y, Cui Y, Wang JF, Lieber CM (2001) Indium phosphide nanowires as building blocks for nanoscale electronic and optoelectronic devices. Nature 409(6816):66–69. doi:10.1038/35051047

Zhong ZH, Qian F, Wang DL, Lieber CM (2003) Synthesis of p-type gallium nitride nanowires for electronic and photonic nanodevices. Nano Lett 3(3):343–346. doi:10.1021/nl034003w

Huang MH, Mao S, Feick H, Yan HQ, Wu YY, Kind H, Weber E, Russo R, Yang P (2001) Room-temperature ultraviolet nanowire nanolasers. Science 292(5523):1897–1899. doi:10.1126/science.1060367

Duan XF, Huang Y, Agarwal R, Lieber CM (2003) Single-nanowire electrically driven lasers. Nature 421(6920):241–245. doi:10.1038/nature01353

Zhuo N, Liu FQ, Zhang JC, Wang LJ, Liu JQ, Zhai SQ, Wang ZG (2014) Quantum dot cascade laser. Nanoscale Res Lett 9(1):144. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-9-144

Tian BZ, Zheng XL, Kempa TJ, Fang Y, Yu NF, Yu GH, Huang J, Lieber CM (2007) Coaxial silicon nanowires as solar cells and nanoelectronic power sources. Nature 449(7164):885–U8. doi:10.1038/nature06181

Bae S, Kim H, Lee Y, Xu XF, Park JS, Zheng Y, Balakrishnan J, Lei T, Kim HR, Song YI, Kim YJ, Kim KS, Ozyilmaz B, Ahn JH, Hong BH, Iijima S (2010) Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nat Nanotechnol 5(8):574–578. doi:10.1038/nnano.2010.132

Bertolazzi S, Brivio J, Kis A (2011) Stretching and breaking of ultrathin MoS2. ACS Nano 5(12):9703–9709. doi:10.1021/nn203879f

Kliros GS (2014) Analytical modeling of uniaxial strain effects on the performance of double-gate graphene nanoribbon field-effect transistors. Nanoscale Res Lett 9:65. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-9-65

Brune C, Liu CX, Novik EG, Hankiewicz EM, Buhmann H, Chen YL, Qi XL, Shen ZX, Zhang SC, Molenkamp LW (2011) Quantum hall effect from the topological surface states of strained bulk HgTe. Phys Rev Lett 106:12. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.126803

Young SM, Chowdhury S, Walter EJ, Mele EJ, Kane CL, Rappe AM (2011) Theoretical investigation of the evolution of the topological phase of Bi2Se3 under mechanical strain. Phys Rev B 84:8. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.84.085106

Liu Y, Li YY, Rajput S, Gilks D, Lari L, Galindo PL, Weinert M, Lazarov VK, Li L (2014) Tuning Dirac states by strain in the topological insulator Bi2Se3. Nat Phys 10(4):294–299. doi:10.1038/nphys2898

Caflisch RE, Lee YJ, Shu S, Xiao YX, Xu J (2006) An application of multigrid methods for a discrete elastic model for epitaxial systems. J Comput Phys 219(2):697–714. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2006.04.007

Johnson HT, Freund LB (1997) Mechanics of coherent and dislocated island morphologies in strained epitaxial material systems. J Appl Phys 81(9):6081–6090. doi:10.1063/1.364357

Niu XB, Lee YJ, Caflisch RE, Ratsch C (2008) Optimal capping layer thickness for stacked quantum dots. Phys Rev Lett 101:8. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.086103

Benabbas T, Francois P, Androussi Y, Lefebvre A (1996) Stress relaxation in highly strained InAs/GaAs structures as studied by finite element analysis and transmission electron microscopy. J Appl Phys 80(5):2763–2767. doi:10.1063/1.363193

Schindler AC, Gyure MF, Simms GD, Vvedensky DD, Caflisch RE, Connell C, Luo E (2003) Theory of strain relaxation in heteroepitaxial systems. Phys Rev B 67(7):14. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.67.075316

Niu XB, Stringfellow GB, Liu F (2011) Nonequilibrium composition profiles of alloy quantum dots and their correlation with the growth mode. Phys Rev Lett 107:7. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.076101

Keating PN (1966) Effect of invariance requirements on the elastic strain energy of crystals with application to the diamond structure. Phys Rev 145(2):637–645

Conesa-Boj S, Boioli F, Russo-Averchi E, Dunand S, Heiss M, Rueffer D, Wyrsch N, Ballif C, Miglio L, Morral AF (2014) Plastic and Elastic Strain Fields in GaAs/Si Core-Shell Nanowires. Nano Lett. 2014 14(4):1859-1864. doi:10.1021/nl4046312

Landau LD, Lifshitz E (1986) Theory of elasticity. Course Theor Phys 7:3

Niu X, Stringfellow GB, Liu F (2011) Phase separation in strained epitaxial InGaN islands. Appl Phys Lett 99:21. doi:10.1063/1.3662927

Niu XB, Stringfellow GB, Lee YJ, Liu F (2012) Simulation of self-assembled compositional core-shell structures in InxGa1-xN nanowires. Phys Rev B 85:16. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.85.165316

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11104010 and 61474014). We are grateful to Prof. Feng Liu and Prof. Anil Virkar for helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

HC conceived the derivations and wrote the manuscript. JW assisted with the calculations and manuscript preparation. EA and HL revised the manuscript. XN conceived the study, revised the manuscript, and supervised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ Information

XN received his Ph.D. degree in Materials Science and Engineering from the University of California, Los Angeles in 2008. Since 2014, he has been appointed as a Professor at the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China. His research interest lies in the modeling and simulation of materials from the atomic to mesoscopic scales.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Wang, J., Ashalley, E. et al. Calculation of Elastic Bond Constants in Atomistic Strain Analysis. Nanoscale Res Lett 10, 403 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1109-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1109-7